Krebs Cycle (The Horror)

TAPP Radio Episode 79

Episode

Episode | Quick Take

Say the term Krebs cycle around anyone who’s had a biology course and watch for signs of stress. In this episode, host Kevin Patton provides a way to make the citric acid cycle less scary by playing into the horror of it all. And we revisit the idea of a standard terminology of anatomy.

- 00:46 | Krebs Cycle Game

- 15:22 | Sponsored by AAA

- 16:07| Proof of Concept

- 25:07 | Sponsored by HAPI

- 25:54 | Riding the Krebs Cycle

- 35:25 | Sponsored by HAPS

- 36:01 | Anatomical Terms Info

- 42:33 | Staying Connected

Episode | Listen Now

Episode | Show Notes

We make up horrors to help us cope with the real ones. (Stephen King)

Krebs Cycle Game

14.5 minutes

In the first season of this podcast, Kevin talked about storytelling—especially playful storytelling—being a key tool for effective college teaching. Especially in A&P. In this first of three segments on part of the story he tells about the Krebs cycle, Kevin talks about leaning into the horror of the Krebs cycle and making a game of that.

- Storytelling is the Heart of Teaching A&P | Episode 12

- Playful & Serious Is the Perfect Combo for A&P | Episode 13

- Actin & Myosin—A Love Story | Episode 15

- The Storytelling Special | Episode 48

- Sigma’s poster Metabolic Pathways my-ap.us/36OE9pn

- Image: my-ap.us/3lz1WOd Credit: Narayanese, WikiUserPedia, YassineMrabet, TotoBaggins

Sponsored by AAA

1 minute

A searchable transcript for this episode, as well as the captioned audiogram of this episode, are sponsored by the American Association for Anatomy (AAA) at anatomy.org.

Don’t forget—HAPS members get a deep discount on AAA membership!

Proof of Concept

9 minutes

Kevin tells the tale about how he came upon proof that people really do react to the Krebs cycle as if it were a horrible monster. At least under certain conditions. And, okay, it’s not peer-reviewed evidence.

Sponsored by HAPI Online Graduate Program

1 minute

The Master of Science in Human Anatomy & Physiology Instruction—the MS-HAPI—is a graduate program for A&P teachers, especially for those who already have a graduate/professional degree. A combination of science courses (enough to qualify you to teach at the college level) and courses in contemporary instructional practice, this program helps you be your best in both on-campus and remote teaching. Kevin Patton is a faculty member in this program. Check it out!

Riding the Krebs Cycle

9.5 minutes

The pyruvate is forced onto a sort of metabolic Ferris wheel, despite the fact that pyruvates are getting onto this carnival ride, but the cars are empty when the wheel comes back around! But coenzyme A grabs the acetyl and forces the pyruvate into the Krebs cycle. And yes, mayhem and gore ensue.

Sponsored by HAPS

1 minute

The Human Anatomy & Physiology Society (HAPS) is a sponsor of this podcast. You can help appreciate their support by clicking the link below and checking out the many resources and benefits found there. Watch for virtual town hall meetings and upcoming regional meetings!

Variation in Anatomical Terms

6.5 minutes

Tony Weinhaus and Sara Sulaiman recently gave a workshop about variability in anatomical terms and revealed the amazing free tool AnatomicalTerms.info (ATI).

- AnatomicalTerms.info (the resource discussed in this episode) https://www.anatomicalterms.info/

AnatoNomina (another online resource based on the Terminologia anatomica) my-ap.us/2GIBJOf - Terminologia anatomica 2nd edition (updated edition; also has links to other current/updated terminology lists) (TA2) fipat.library.dal.ca/ta2/

- UPDATE: TA2 has now been officially approved by IFAA.

- UPDATE: TA2 viewer (an easy way to navigate Terminologia Anatomica 2nd edition in an online viewer) ta2viewer.openanatomy.org/

- New Terminologia Anatomica: Cranium and extracranial bones of head (article going through some of the updates in the new edition) my-ap.us/3nw9Utc

- Understanding Anatomical Latin (short booklet on basic principles of Latin as it’s used in anatomical terminology) my-ap.us/3nBvgWc

Need help accessing resources locked behind a paywall?

Check out this advice from Episode 32 to get what you need!

Episode | Captioned Audiogram

Episode | Transcript

The A&P Professor podcast (TAPP radio) episodes are made for listening, not reading. This transcript is provided for your convenience, but hey, it’s just not possible to capture the emphasis and dramatic delivery of the audio version. Or the cool theme music. Or laughs and snorts. And because it’s generated by a combo of machine and human transcription, it may not be exactly right. So I strongly recommend listening by clicking the audio player provided.

This searchable transcript is supported by the

This searchable transcript is supported by the

American Association for Anatomy.

I'm a member—maybe you should be one, too!

Introduction

Kevin Patton:

The horror fiction novelist Stephen King once explained the popularity of that genre by stating, “We make up horrors to help us cope with the real ones.”

Aileen:

Welcome to The A&P Professor, a few minutes to focus on teaching human anatomy and physiology with the veteran educator and teaching mentor, your host, Kevin Patton.

Kevin Patton:

In this episode, I discuss modern anatomical terminology. And I talk about how we can teach the Krebs cycle by playing into the horror of it.

Krebs Cycle Game

Kevin Patton:

The Krebs cycle. Now, we probably just had a little bit of an emotional response in hearing that term, Krebs cycle. I think that’s pretty common. Actually, I have proof that that’s pretty common and I’ll tell you about that a little bit later in the story. But right now, I want to talk about why I’m bringing up the citric acid cycle, otherwise known as the Krebs cycle. And you noticed that I left a little pause after I said Krebs cycle and the reason is that that’s part of a game that I have played with my students for decades. That’s part of the story I tell of the Krebs cycle.

Kevin Patton:

Now, I’ll get back to that little gap in a moment. But before I do, I want to pause, again, for a moment and talk about this idea of storytelling. This is something I talked a lot about in the first season of this podcast. So if you go to the show notes or the episode page, I’ll put in there links to some of those early episodes where you can go back in where I talk about storytelling as a technique, not only for doing lectures, but really any kind of teaching. If it involves a story, in our case, the story of the human body, then it’s going to be more effective.

Kevin Patton:

And I also, in some of those early episodes, talk about the idea of the stories being playful. The more playful they are, the more engaged the students become in our story and so therefore, the more they’re going to understand the story. And the more they’re going to remember the story and therefore, the more effective it’s going to be. So playfulness is good. Stories are good. The other thing that’s good is interaction…

Kevin Patton:

Now if you’ve ever been to a live theater performance or any kind of live entertainment, even like a walking tour, while you’re visiting some other part of the world, if that tour guide includes the tourists in his or her spiel, then you’re going to get a lot more out of it. It’s going to be a more fun experience. You’re going to remember more of it or you’re going to become more engaged. And I still remember some walking tours I’ve been on in various parts of the world where the tour guide designated this tourist is going to be this character and Kevin over here, he’s going to be the king of whatever or Benjamin Franklin or whoever it is that’s going to be part of the story being told. And when we’re expected to have lines, that is we’re supposed to react in a certain way and say something out loud as we play our role.

Kevin Patton:

Or if you’ve ever been to one of those like mystery dinner theaters or something and you’ve been given a role to play, you know that not only does that increase engagement and increase the fun, but you remember it for a long time after. Whereas a play that was very good that you went to and you just sat and listened to the whole thing may not have been so engaging and it may not have been so memorable. So I think that if we can make our classes, especially our lectures, where there’s this very strong chance that we’re going to lose our students very early on in a lecture, if we can engage them, then it works better.

Kevin Patton:

So how does that fit into the Krebs cycle? Well, I start out telling students that we’re going to be covering something that is very important for our understanding of the human body but is also a scary thing. And not only is it scary, it’s scary to everyone. It’s scary to me. I’ve had some experiences as a student in the way, way, way past where I’ve had to memorize some parts of the Krebs cycle and surrounding metabolic pathways and that wasn’t fun. And I’ve been asked questions that I wasn’t able to answer because I wasn’t that well prepared because, frankly, biochemistry is something you have to really wrestle with and think about and really work at getting to an understanding of it.

Kevin Patton:

And so when we think about the work it takes and some of the failures that we may have had before we got to a point where we understood things then yeah, that can have a negative connotation. And we can remember it as being kind of scary or kind of difficult or kind of negative in some way, even if we’re now at a point where it’s not so bad. And so what I do at my students is I say, “Look, this is scary, it’s scary for everybody. Back in the olden days, they made us do a lot more memorization of it and working with it at a beginning level than we now understand is really necessary. So I’m not going to ask you to do that.

Kevin Patton:

“The problem is, though, dear students, is that there’s all these people of my generation and earlier generations, and even later generations, that have had to really wrestle with the Krebs cycle. And so if it comes up in conversation and your reaction is like, ‘Oh, yeah, the Krebs cycle, I have that. I understand about the Krebs cycle,’ and you’re all happy about it and you’re confident about it, they’re going to look at you and think this person never had the Krebs cycle.”

Kevin Patton:

Because when I say that term, Krebs cycle, the proper response should be, “Oh no, not the Krebs cycle.” And so if you don’t have that, students, if you don’t have that appropriate reaction, then that person who brings it up is going to think, “Oh, they’re not very well trained.” They might even ask you, “Who was you’re A&P teacher? And what school did you go to?” That could reflect badly on our school and therefore, on your own credentials, and it could reflect badly on me. And after all, it’s all about me, right?

Kevin Patton:

So I don’t want people to think badly of me because you’re not reacting appropriately when you hear the term Krebs cycle. So I have two choices as a teacher. One choice is to really go overboard, like some of my early teachers did, and really spend a lot of time on the Krebs cycle, really make them memorize a lot of those metabolic pathways that lead into and out of the Krebs cycle and even the Krebs cycle itself and understand every step along the way and have them repeat it back.

Kevin Patton:

I remember having a test. I just have little bits of memory about this. But I do remember having a test where one of the questions was an essay test. And one of the questions was, not really a question, it was a directive. It said, “On this sheet,” it was a blank sheet, “draw out how much of the Krebs cycle you remember and highlight the important parts.” And I remember just staring at that sheet because I really did feel well prepared but I wasn’t prepared for a blank sheet. I was prepared for questions about the Krebs cycle. I was prepared for recognizing parts of the Krebs cycle, I was not prepared for drawing it out.

Kevin Patton:

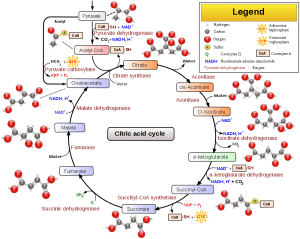

But my teacher thought that was important and you know what, I don’t need to have to draw it out. All these years, even working with Krebs cycle, teaching the Krebs cycle, I don’t need that. As a matter of fact, people who work with the Krebs cycle in their research, they’re usually so focused on one little part of it, they don’t have the whole rest of it memorized. I mean, really, anybody who’s had to memorize any part of it, they don’t remember it. And so I pull out of this tube that I bring with me, on the day we talk about the Krebs cycle, I bring out my three foot by four foot poster from Sigma Chemical who’s now, I think, MilliporeSigma or something, they still make this. It’s called metabolic pathways, I just looked it up. It’s in the 22nd edition of this poster.

Kevin Patton:

And this poster, even though it’s three by four feet, you have to really get up close and squint to see all of the different steps that are highlighted. And it’s not like overly annotated or anything where it’s mostly not the metabolic pathways and that’s why it looks so complicated. No, it’s just the metabolic pathways. And I’d say about a third of it is the Krebs cycle and the things leading immediately into and out of the Krebs cycle. And so we know that that is then connected to all kinds of other metabolic pathways, and some of those are represented too.

Kevin Patton:

So, I say, “Okay, even if you’re just looking at this one part that actually is the Krebs cycle.” I mean, really, that’s crazy. The whole class, I usually… I’ve used it in classes up to 300 but I’m thinking more of my community college where I would have between 36 and 48, depending on which semester it was, students in that classroom, and I’d hold that up and they couldn’t see what was going on. So I’d walk around with the classroom, have the students gather around and look at it and so on, and they’re just like shaking their heads. And they’re thinking, “Okay, is this like one of the stories he tells when he says that he had walked uphill both ways to get to school and get there early to light the fire before the teacher came in and all that kind of stuff? Or did this really happen?”

Kevin Patton:

And so I tell them, “Look, I never had to memorize all this. Nobody ever had to memorize all of this, but there were parts I did have to memorize. And looking back, I think we really went far too deeply into it and had to do things that really don’t help our understanding so I would much rather give you this version.” And then I throw up a version from our textbook, and not the one that shows the actual details of the Krebs cycle. I throw up the one that kind of puts it all together and it’s the simplified version of it. And no matter what textbook you use, you’re going to have a version of the Krebs cycle and some of the pathways leading into and out of it, that is a simplified version to give you the overview.

Kevin Patton:

And I say, “Look, this is what I think is most important for you to learn. But the problem is, is that if I just teach you this, then your credentials might be at risk because of what I just told you because you’re not going to react appropriately. You can say, “Oh, yeah, the Krebs cycle that wasn’t so hard,” and it’s going to reflect badly on me. And I don’t want that to happen.” So that’s kind of a game I play with them, too. Of course, I don’t care that it’s going to reflect badly on me. I don’t care what students are saying that goes… Well, yeah, okay, I do care a little bit, but not that much.

Kevin Patton:

I mean, it’s really something I over emphasize to just, again, be playful with them. So I tell them, “You have a choice. We can either learn it the hard way, and I can do that. Been there, done that, I can do that. So that you will react appropriately and so your credentials will have worth. Or the other choice is we can, looking at the simplified chart, we can do it this way but you’re going to have to practice acting out an appropriate emotional response to the Krebs cycle.” Then I stop and I just look at them.

Kevin Patton:

I say, “Okay, if it’s going to work. Every time I say the term Krebs cycle, and it’s going to come up a lot, it’s going to come up when we… I first introduced this when we’re talking about cells, but it’s going to come up when I talk about muscles and it’s going to come up again, when I talk about digestion and nutrition. And it’s going to come up again. Well, here and there and here and there, it’s going to come up as a reminder of here’s how the whole metabolic pathway kicks in. And even if I don’t have to use the term Krebs cycle in those later iterations, I will. I’ll make sure that I use the term. Remember those metabolic pathways, including the Krebs cycle that… so and so forth.”

Kevin Patton:

And I always build in a pause because I tell them, “From this moment forward, we’re going to have an agreement with each other that every time you hear the term Krebs cycle, whether it’s in this classroom or outside this classroom, every time you hear the term Krebs cycle, you’re going to react by saying, ‘No, not the Krebs cycle’ or something equivalent to that. And so starting right now, so let’s say it, Krebs cycle,” and then I wait for them. There’s kind of look at me like, “Is he serious?” They know me well enough by then to know yeah, I’m serious.

Kevin Patton:

So one or two of the better students will say, “Oh, no, not Krebs cycle.” I say, “Wait a minute, nobody’s going to believe that. It has to be believable.” But in acting, you don’t get to that really believable performance right away so that’s okay, but you have to try it. We’re going to read the lines at first. And then as time goes by, we’re going to put more and more emotion into it. So by the time I’m finished with you, you’re going to have a believable and immediate reaction so people are going to say, “Whoa, whatever A&P course he took, wherever he learned about the Krebs cycle, it was serious. They really know what they need to know about Krebs cycle.”

Kevin Patton:

And of course, we all know what you really need to know about the Krebs cycle for most context is not all those individual steps. You need to know the story of the Krebs cycle. You need to know the overview of the Krebs cycle. You need to know the importance of the Krebs cycle in the context of the entire function of the human body. So yeah, they’re going to be right in that estimation. They’re going to be wrong about how much detail you know or how much detail you were ever asked to know. But they’re going to be right about the fact that you know enough and so they agree, “Okay, we’re not going to memorize this chart so I can roll that up and put it away, but I’m going to keep it handy because I know that the next few times that I say Krebs cycle.”

Kevin Patton:

Now, you’re not responding, are you? Even though you’re listening to a podcast episode, and I don’t care if there are other people around you who have no idea what you’re listening to, just practice that reaction. “Oh no, not Krebs cycle.” I guarantee it will up your game. It will Increase your value in the eyes of your peers if you have that kind of reaction. And I’m going to come back to this in a moment, but I told you a few minutes ago that I would give you proof that this is an actual thing.

Sponsored by AAA

Kevin Patton:

A searchable transcript and a captioned audiogram of this episode are funded by AAA, the American Association for Anatomy.

Kevin Patton:

One of the things that I love about being a member of AAA is that I get access to the journal, Anatomical Sciences Education. Every issue has a lot of very useful information that helps me in my teaching. And it’s not just about anatomy teaching, which I learned a lot from. There’s also plenty of content focused on the kind of combined A&P that I teach. Want to check it out? Just go to anatomy.org.

Proof of Concept

Kevin Patton:

I was doing this with my students at the very beginning of our community college, where I and one other A&P teacher, we were the very first faculty members of the science department of our college, we were the founding faculty. And we were in a previous school that was much smaller than the beginning of our community college, so our faculty offices were really cramped. And so we had what used to be a closet, literally used to be a closet. And we had, I think we had five people in there at the time. We had two full-time faculty and me and this other first faculty, and then we had a number of adjunct faculty and I think we had some faculty from other departments in there, too.

Kevin Patton:

And so they were in there too and literally, I was at the very end because I had, I think, a one-week seniority over the next person on the scheme there. I got to pick the first desk and so I picked the one next to the window and there’s a window air conditioner there. Said, “Yup, that’s where I’m sitting.” The thing is, when I came back from class, everybody else in the office had to get up, step out into the hallway so I could get to my desk. It was that cramped.

Kevin Patton:

So I remember sitting there next to the air conditioner and my colleague coming in. She not only taught A&P, but she taught microbiology. And she came in and threw her books down, or at least I remember it that way. I think she just had a big… I don’t know, this stuff and it just kind of fell. I don’t think she was really throwing it because she wasn’t upset in an angry way. She was actually being kind of playful with me. She’s saying, “What are you telling your students?” And I’m like, “What? Wait a minute. Let me turn off the window air conditioner here. What did you say?” She said, “Today, in micro, a lot of the people in my micro class, they just had you in A&P and we’re in the same classroom. And so I came in and I said, ‘Okay, today, we’re going to start talking about the Krebs cycle,’ and half of the class start yelling, and they’re going, ‘Oh, no, not the Krebs cycle.'” And I just started laughing.

Kevin Patton:

And I said, “Oh, my gosh, they’re doing it in other classes. Well, I told them to do it every time they hear the term Krebs cycle.” And she says, “What is that about? What are you making them do with the Krebs cycle that they’re reacting that way?” And so I told her what I was doing. And she says, “Oh, I don’t think people really react that badly to it.” And I said, “Well, I mean, thinking back to your own experience of when you first learned the Krebs cycle, did you find that it was an easy thing that you just immediately got it and none of it was challenging to you?” She said, “Well, no, you’re right. It was challenging enough but I don’t burst out with, ‘Oh, no, not that Krebs cycle.'”

Kevin Patton:

I said, “Well, okay, maybe that’s taking it a little far. But in your brain, maybe you’re doing a little bit of that.” And she said, “Yeah, I don’t know” and she says, “Well, can you just tell them to stop doing it in my class?” So they did keep doing it a little bit. And I think she started playing the game too, because she’s just the kind of person that I think would pick up on that and would take it further. Maybe twist it around into something a little bit more like her style of teaching. But where’s the proof come from? That kind of disproves my theory, doesn’t it?

Kevin Patton:

Well, okay, it was the next year, I guess it was, and I went to a HAPS annual conference in San Diego, the very first one. Gosh, when was that? It was like ’80, ’90, oh my god. I’m not that old. Okay. It was 1991 or 2, maybe, I think. Yeah, but it was way long ago.

Kevin Patton:

At that San Diego HAPS meeting, there was one day where they had arranged a field trip for us and we were going to go to the San Diego Zoo. So we were there early in the morning out in the parking lot of the conference hotel, waiting for the bus to arrive to take us to the San Diego Zoo. And everybody had a cup of coffee in their hand and a doughnut or something like that, because knowing a lot about the Krebs cycle, thank you, and its different metabolic pathways that are associated with it, we know that the best thing to eat in the morning to get going is a doughnut. Because it’s got all those sugars and fats and I don’t know. Is there any protein in a doughnut? I don’t know, but it was we don’t need the protein for energy. The sugars and fats are going to give us energy.

Kevin Patton:

And so yeah, we’re standing around and we’re just chatting about things and somebody, I guess you get this conversation a lot at HAPS meetings, and that is, somebody will ask, “Well, how much do you go into this topic or that topic?” Because we’re all kind of uncertain all the time. I’ve been teaching for decades and I still like, “Do I tell them enough about this topic? Do I ask enough of my students regarding this concept, and so on?” So we’re always questioning ourselves, which I think is good. But, and I think that’s one of the many values of going to these meetings, like HAPS meetings, or being part of The A&P Professor community, or any of these opportunities that we have. The AAA has not only the meetings but it has various courses and seminars and so on going on.

Kevin Patton:

Any of that networking that we do, part of the value is that we can bounce that off of and get their ideas on it. And somebody brought up Krebs cycle. Yes, the Krebs cycle. And so all kinds of people, I think the way it was brought up was, “There’s a lot of stuff that I’m teaching in my course, but back when I had to take biochemistry or I had to take this course or that course, for example, when we talked about the Krebs cycle…” And as soon as they said Krebs cycle, everybody in the group, or at least most people in the group, I remember it as everybody. Okay, in my memory, I remember people leaning out of their windows in the hotel, saying this, and they all reacted the same way, saying, “Oh, no, not the Krebs cycle” except for me.

Kevin Patton:

I got this huge smile on my face. And I said, “Oh, yes, the Krebs cycle.” And they all looked at me and they said, “You are one weird dude. I mean we already knew that but you’re like the only person who liked the Krebs cycle.” And I said, “No, I hated the Krebs cycle. The reason I’m reacting this way is because this proves my theory of the game that I play with my students. This game that we play in our class that my colleague questioned, but here it is, here’s proof that people really do react that way.” And so now I had ammo the entire rest of my career and I’m using it again now.

Kevin Patton:

So yeah, okay, the Krebs cycle, this horrible, horrible thing that really isn’t so horrible. Once you understand the basic premise of it, it’s not that bad. But I play into the horror of it, I lean into the horror of it and say, “Look, this scares a lot of people but we know better. We don’t need to be scared, but we’re going to pretend to be scared.” And that’s going to be our game. And it makes it fun for the students and it engages the students. And you know what, I do keep that up. I even will have students run into me somewhere, not so much recently, because I don’t really go anywhere right now because of the pandemic. But up until that, for all those years, I would run into somebody in the mall. So yeah, that was a long time ago. Nobody goes to malls anymore. Or just different things, and they say, “Oh, remember, I was in your A&P class,” and we’ll chat a little bit.

Kevin Patton:

This happens probably to you a lot, too. There’s some one or two things that really pops into their mind when they meet you about, “Oh, I remember this in class. Remember that one guy that was in our class,” or, “Remember this,” or “Remember that time that we all went outside and you were telling stories” or whatever. And that’s one of the things that sometimes will come up and they’ll say, “Oh, I remember the Krebs cycle,” and then they’ll look at me and I will say and I even had my kids at one point doing this, they would go along and play the game with me and we’d all react to this former student. We all say, “Oh, no, not the Krebs cycle,” and they would look at me and they would look at the kids. They would just burst out laughing because they had remembered that and that’s why they brought it up but to have me have trained my family to do it as well, they just thought, “Kevin, you are one weird dude.”

Kevin Patton:

Yeah. Okay, this is a widespread perception of who I am and I’ll own it. Yeah, I am weird. I know it.

Kevin Patton:

Getting back to this idea of the Krebs cycle, there’s more to it. I’ll tell you more about it when we come back.

Sponsored by HAPI

Kevin Patton:

The free distribution of this podcast is sponsored by the Master of Science in Human Anatomy and Physiology Instruction, the happy degree. It’s a flexible online program to help anyone already having an advanced degree review all the major concepts of A&P and how to teach them using contemporary teaching strategies that can help with online, remote, on-campus and hybrid teaching. And it’s all done within a supportive and collaborative network of peers. Check out this online graduate program at nycc.edu/hapi. That’s H-A-P-I or click the link in the show notes or episode page.

Riding the Krebs Cycle

Kevin Patton:

In a previous segment, I was talking about the Krebs cycle. Oh, no, not the Krebs cycle. Come on, you can play this game. It’s fun. But yeah, okay, it’s not fun at first, because you don’t understand the game, I get that, but just play long. All right. And eventually, you’re going to be happy with the game, you’re going to enjoy the game.

Kevin Patton:

So I was talking about the Krebs cycle. Yes, thank you. Even if you’re just doing it in your head, that’s good. That’s okay. That’s how you start. We’ll eventually get to the learning out part of it. But when I do that with my students, we’re talking about the energy. I mean, it’s all about energy, right? And we start with the glucose molecule. That’s where we always start that story, isn’t it, with the glucose molecule, and we get that into our body, and we get that into the cell, and now the cell has this problem. How are we going to get the energy that is stored in that glucose molecule? How are we going to get it out and then eventually get it to that myosin head or that pump in a membrane somewhere or whatever other process that we know requires energy. They’re going to get it from ATP so we know that that’s somewhere in the story, but that’s kind of down the line.

Kevin Patton:

So we need to know how does the energy get out of the carbohydrate molecule and into the ATP. And I’m not going to tell that whole story but I’m going to give you the idea of what I do with it in this playful way, how I connect that to this horrible story of the Krebs cycle. Yes, thank you, the Krebs cycle. We’re talking about breaking apart the carbohydrate molecule and the energy that’s in the bonds of the carbohydrate molecule end up flying away as high-energy electrons. So, remember, I’m telling a story here so they can picture in their mind’s eye these flying electrons. And of course, the proton, it’s going to come along for the ride, like, “Hey, wait a minute.” It’s like when your dog breaks the leash and you run after your dog and say, “Wait a minute.” Of course, the dog’s got all the energy and you’re just trying to keep up and you’re going to try to stick along with your runaway dog.

Kevin Patton:

And so this high-energy electron goes flying away, but we need to capture that energy, we need to catch that high-energy electron and move that energy into a usable form, eventually into ATP. So it’s going to be done in stages because there’s dozens of ATPs’ worth of energies, almost three dozen ATPS’ worth of energy in every one carbohydrate molecule, every one glucose molecule, at least. So we take that glucose and we break it apart. We get some of those high-energy electrons flying off and we have coenzymes. They’re going to catch them and they’re going to take them someplace where that energy can then be transferred to ATP. And we’ll talk about where that is going to happen later in the story is what I tell my students, but there’s still a lot of energy left in that molecule and we eventually get to this molecule called pyruvate.

Kevin Patton:

So basically, what we’ve done with the pyruvate is we’ve taken the glucose molecule and broken it in half. So we have this six-carbon molecule has now been broken into two three-carbon molecules. But there’s still a lot of energy left in there so what are we going to do with it? We’re going to break off another one of those high-energy electrons. And now we’re down to acetyl, which is only two carbons, but there’s still a lot of energy left in there. So the acetyl, we’re going to take that and move it into this circular metabolic pathway.

Kevin Patton:

Yeah, that’s weird to have a circular pathway. And yeah, that’s why it took so long to figure out how it works because we weren’t necessarily expecting a circular pathway. So sure, this guy named Krebs, he kind of was one of the people that you know, and he’s given all this credit for figuring it out. And so his name is on the Krebs cycle. Oh, no, not the Krebs cycle. So we have that reaction because by then they’re acting pretty good about this. And so that two-carbon acetyl goes into the Krebs cycle, and then I say… They react again, “Oh no, not the Krebs cycle” and say, “You’re right. It’s scary, even for the acetyl molecule.” For that little acetyl group, it’s not going to go willingly into the Krebs cycle. “Oh no, not the Krebs cycle.” And so what do you do?

Kevin Patton:

You need something to grab a hold of the acetyl and push it kicking and screaming into this cycle. Imagine it like a Ferris wheel. So here is I put up a picture of the Ferris wheel that was at the St. Louis 1904 World’s Fair, which was reconstructed, put back together again from a previous World Exposition in Chicago a few years before that where they had street cars as the cars. They had, I think, 40 of them all together. And I mean, it was a big giant Ferris wheel, built by Ferris, the engineer who designed it. And so I put up a picture of that Ferris wheel before it was demolished and buried somewhere. That’s a big mystery in the St. Louis area. Where are the pieces of the Ferris wheel?

Kevin Patton:

I think they’re kind of scattered all over. But anyway, I always tell my students, “Yeah, and I have a piece of it in my office. If you come during office hours, then maybe you’ll see it.” Okay, I got to do whatever I can to get people to come to office hours, right? So anyway, so here’s this big giant Ferris wheel and you look up there and you see that there are body parts flying off of it. This is like a Stephen King novel or something where and you see people get on, you see body parts flying off. And then when that car comes back around, there’s nobody left in that car. And now they’re asking you to get on that car. “No, I’m not getting on there. That’s a scary Ferris wheel. That’s a horrible Ferris wheel. I’m not getting on.” So coenzyme A comes up and says, “Buddy, you’re getting on?” And I’m like, “No, I’m not.” It latches on and I can’t get away. And guess what, I get pushed on to that Ferris wheel, the citric acid cycle, the Krebs cycle. “Oh, no, not the Krebs cycle.”

Kevin Patton:

And sure enough, these carbons get broken apart and those high-energy electrons go flying off and these coenzymes grab them as they fly off. And then we’re ready for that next part of the story, the electron transport system. And this is where that energy is converted from one form to another and eventually ends up in the ATP. And I’m not going to go into that story completely. But I liken the process to a hydraulic dam, an old-style water wheel that powered the old mills and other kinds of machinery in the very early parts of the Industrial Revolution and before, where you had this energy of the water moving down the dam, causing the water wheel to move, being converted into this mechanical energy inside the mill that was grinding the grain, or doing other jobs, depending on what kind of mill it was.

Kevin Patton:

So okay, I kind of told the story. But we switched to a different kind of story that’s not so scary because that scary one is over. Except we do kind of review that again and talk about, “Oh, that big scary thing was happening to the electron and it got pushed onto this horrible Ferris wheel and then it flew off and then it got caught by a coenzyme and taken over to this other pathway. Now I’m pooped out and it’s meeting up again with its proton, which remember was chasing along, wanting that electron back.” So the proton says, “I don’t believe any of that. That is the craziest story I ever heard.” But they hug they, get back together, joined an oxygen so that they’re stable and ride off into the sunset and live happily ever after. Until, of course, this horrible mess starts, again, maybe somewhere along the line in the lives of those little pieces of matter.

Kevin Patton:

So, okay, that’s just kind of a crazy story. And it may have sounded a little disjointed because I didn’t tell it exactly the way I tell it in class, because I kind of embellish a little bit and get even more dramatic and wait for student responses. And I do repeat it more than once over the course of time. And it does keep coming up because as I said, and as you know, the Krebs cycle. Oh, yeah, the Krebs cycle, it does come up a lot. I mean, it really is a core piece of the story you’re better to know about when you’re talking about these other kinds of things. Why we need vitamins, why we need nutrients, why what happens in a muscle happens in muscles, how fatigue occurs and different things like that. Yeah, or how rigor mortis occurs. That becomes part of this, an extended part of the story.

Kevin Patton:

So if you think this is the stupidest thing ever, that’s fine, that’s okay. And it just helps to confirm your attitude of Kevin being a weird dude. That’s okay. But on the other hand, if there’s some little piece of that or if it sparks in your mind some other kind of story that you can tell. The more dramatic it is, the more weird it is, the better it’s going to be for your students. So play around with that, have fun.

Sponsored by HAPS

Kevin Patton:

Marketing support for this podcast is provided by HAPS, the Human Anatomy and Physiology Society, promoting excellence in the teaching of human anatomy and physiology for over 30 years.

Kevin Patton:

I just participated in a regional conference about a week ago and I’m getting ready to join in the next one, which is on November 7th. Want to join me? Well, just go visit HAPS at theAPprofessor.org/haps. That’s H-A-P-S, and tell them I sent you.

Anatomical Terms Info

Kevin Patton:

I talk a lot about terminology in this podcast. And even though I’m not doing a word dissection in this episode, I am going to talk a little bit about terminology, specifically anatomical terminology. And the reason why it’s on my mind is last week, I went to the joint HAPS-AACA regional conference. And at that conference, one of the several really good workshops that I went to was one on anatomical terminology. It was hosted by my friend Tony Weinhaus at the University of Minnesota Medical School and Sara Sulaiman who’s at the School of Anatomy at the University of Bristol in the UK. And they introduced their topic by talking about the fact that we’re still highly variable among ourselves as teachers of human anatomy in terms of our terminology. There’s a lot of variability that exist, even though, for many years, there have been international lists with the goal of that becoming the standard.

Kevin Patton:

And just to make their point, they gave those of us attending the workshop these questions, these anonymous polls, in which we were asked, which of these terms that are listed here is the one you use to teach to your students. And then here’s another one, here’s another one, and it was variable among us. Now, that’s tempered a little bit by the fact that when I look at the list, they said, “Well, which one do you teach your students?” “Well, I teach them more than one of those on the list.” And I think that issue came out in our discussion at the workshop as well is that we don’t always just give our students one version of a term, we might have preferred one that we use most often, but we will lay out several others. And so it was a really interesting discussion on this whole idea of international lists.

Kevin Patton:

And, by the way, the most often used international list of anatomical terms is Terminologia Anatomica or TA for short. And that is published by International Federation of Associations of Anatomists. That’s IFAA for short. And that’s been around for a long time. And what I learned in this workshop is there’s a new edition out and I didn’t realize it. It just came out not long ago and I don’t think it’s actually got the official last approval yet, but it’s out there and you can get it. And there’s a link in the show notes and the episode page at theAPprofessor.org/79. And you can go in there and look at it yourself.

Kevin Patton:

And I really do use that to see, well, what does the international list say. And I will most often use that one in my teaching. But I also know that my students are going to be going out into various contexts, like their clinical situation, where their supervisors and their colleagues are using terminology that doesn’t match up because they learned their anatomy a long time ago and they’ve gotten used to that. And when I’m doing some of my research for revising my textbooks and so on, or if I’m teaching and I’m going to be teaching a new topic that I don’t usually teach, I’m going to go back into those international lists. But I also go into the literature and do a literature search and see, well, is that one the most often used one? Is this older term more often used or is it still used at all, even? And what I find is, well, something we confirmed in the workshop, there’s a lot of variability.

Kevin Patton:

Even in the published literature, in the primary literature, they’re not necessarily using the version from the international list. So that’s interesting, and it’s really important for us as teachers to kind of try and get a handle on this. It’s a very slimy kind of thing. You can’t just grab a hold of it and have it in your hand. That slips out because there’s all this variation.

Kevin Patton:

Now, one of the reasons I’m bringing this up in this episode is that there is this really cool tool for discovering some of the variability of anatomical terminology that I had never heard of before. At least I don’t think I have. I mean, honestly, there was a little vague recollection that was triggered, but it’s mostly like, “Whoa, why don’t I use this all the time? Why isn’t this in my list of bookmarks?” I do have a whole folder in my bookmarks on anatomical terminology and this wasn’t in there, so maybe I had never seen it before. It’s called AnatomicalTerms.info or ATI for short. Once again, AnatomicalTerms.info and again, there’s a link in the show notes and episode page, and you can go to it and it is so cool.

Kevin Patton:

When you first log into it. Well, that is when you first go to the homepage, all you see is a blank search box, so it doesn’t look like much, but type an anatomical term into that search box, and you’re going to be blown away, because what’s going to come back is a whole list of different versions of that term and it’s going to show you well, what’s the version that’s in the preferred term in the Terminologia Anatomica. And even within that, it’ll give you the English and the Latin and not just the English, it’ll give you US English and UK English.

Kevin Patton:

Also, it might have a German version, or a French version, or a Spanish version or who knows what. So it’s kind of a wiki type thing, the way I understand it, in that you can join, you can get an account and you can go in there and suggest changes, you can suggest additions. And if you do log in, and I did that, when I log in, I can also see who first contributed it, who made edits to it and so on, sort of like you can do in Wikipedia.

Kevin Patton:

This project, AnatomicalTerms.info is a project of Leiden University Medical Center in collaboration with the American Association of Clinical Anatomists, the AACA. And of course, it was the AACA who were co-sponsors of the workshop or the whole regional conference that I just went to along with HAPS. So wow, this is so cool. I don’t know if I’m ever going to get done playing with it. And I just wanted you to join in the fun and give you that information.

Staying Connected

Kevin Patton:

I always put links in the show notes and at the episode page at theAPprofessor.org/79 in case you want to further explore any ideas mentioned in this podcast or if you want to visit our sponsors. And you’re always encouraged to call in with your questions, comments and ideas at the podcast hotline. That’s 1-833-LION-DEN or 1-833-546-6336 or send a recording or a written message to podcast@theAPprofessor.org. We’d love to have you in our private online community well away from all the ads and spam and tracking and algorithms that hide what and who you want to see, the convoluted email threads and the online bullying. It’s away from all of that. It’s a comfortable, supportive space filled only with A&P faculty like you. Just go to theAPprofessor.org/community. And you know what, I’ll see you down the road.

Aileen:

The A&P Professor is hosted by Dr. Kevin Patton, an award-winning professor and textbook author in Human Anatomy & Physiology.

Kevin Patton:

For your own safety and the safety of others, please do not put your hands outside the car when the Krebs cycle is in motion.

This podcast is sponsored by the

Human Anatomy & Physiology Society

This podcast is sponsored by the

Master of Science in

Human Anatomy & Physiology Instruction

Transcripts & captions supported by

The American Association for Anatomy.

Stay Connected

The easiest way to keep up with new episodes is, um, wherever you already listen to audio!

Click here to be notified by email when new episodes become available (make sure The A&P Professor option is checked).

Call in

Record your question or share an idea and I may use it in a future podcast!

Toll-free: 1·833·LION·DEN (1·833·546·6336)

Email: podcast@theAPprofessor.org

Share

Kevin's bestselling book!

Available in paperback

Download a digital copy

Please share with your colleagues!

Tools & Resources

TAPP Science & Education Updates (free)

TextExpander (paste snippets)

Krisp Free Noise-Cancelling App

Snagit & Camtasia (media tools)

Rev.com ($10 off transcriptions, captions)

The A&P Professor Logo Items

(Compensation may be received)

🏅 NOTE: TAPP ed badges and certificates can be claimed until the end of 2025. After that, they remain valid, but no additional credentials can be claimed. This results from the free tier of Canvas Credentials shutting down (and lowest paid tier is far, far away from a cost-effective rate for our level of usage). For more information, visit TAPP ed at theAPprofessor.org/education