Making Mistakes Teaching Anatomy & Physiology

TAPP Radio Episode 63

Preview Episode

Preview | Quick Take

A brief preview of the upcoming full episode, featuring upcoming topics—making mistakes, how stress grays hair, a new kind of immune cell—plus word dissections, a book club recommendation (Mary Roach’s Gulp!), and more!

00:18 | Topics

01:19 | Sponsored by HAPI Online Graduate Program

01:49 | Word Dissection

10:30 | Sponsored by HAPS

10:51 | Book Club

13:28 | Survey Says…

13:57 | Sponsored by AAA

14:13 | Staying Connected

Preview | Listen Now

Preview | Show Notes

Upcoming Topics

1 minute

- Making mistakes in teaching. In front of students!

- Stress causes hair to gray. But how, exactly? A surprising answer.

- Not a B-lymphocyte. Not a T-lymphocyte. An X-lymphocyte!

Sponsored by HAPI Online Graduate Program

0.5 minute

The Master of Science in Human Anatomy & Physiology Instruction—the MS-HAPI—is a graduate program for A&P teachers. A combination of science courses (enough to qualify you to teach at the college level) and courses in contemporary instructional practice, this program helps you power up your teaching. Kevin Patton is a faculty member in this program. Check it out!

Word Dissection

8.5 minutes

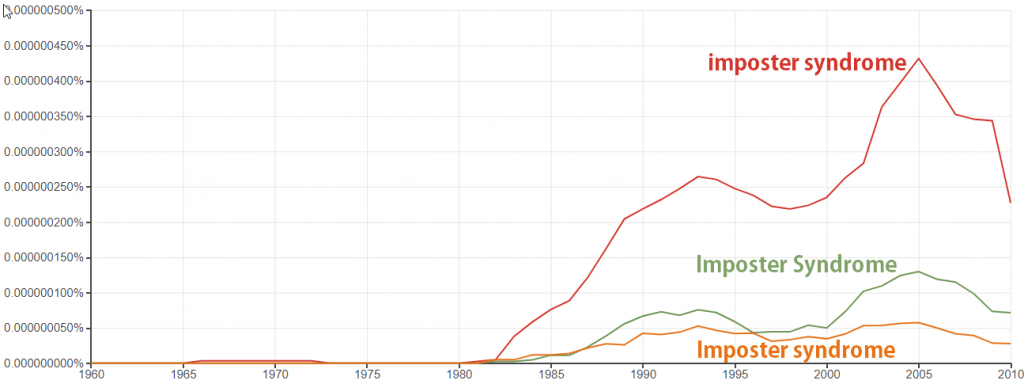

- Imposter syndrome

- The Impostor Phenomenon in High Achieving Women: Dynamics and Therapeutic Intervention (the paper that started it all) my-ap.us/2HFVXVX

- Imposter syndrome usage via Ngram Viewer my-ap.us/2HJuJ0p

- Norepinephrine

- Noradrenaline

- Adrenergic

- Melanin

- Eumelanin

- Pheomelanin

- HLA

Sponsored by HAPS

0.5 minute

The Human Anatomy & Physiology Society (HAPS) is a sponsor of this podcast. You can help appreciate their support by clicking the link below and checking out the many resources and benefits found there. Don’t forget the early-bird discount for the HAPS Annual Conference expires on February 21, 2020—the same deadline for submitting workshops and posters.

Book Club

2.5 minutes

- Recommendation from Mike Pascoe

- Gulp: Adventures on the Alimentary Canal

- by Mary Roach

- amzn.to/2HE3KDO

- Gulp: Adventures on the Alimentary Canal

- For the complete list (and more) go to theAPprofessor.org/BookClub

- Special opportunity

- Contribute YOUR book recommendation for A&P teachers!

- Be sure include your reasons for recommending it

- Any contribution used will receive a $25 gift certificate

- The best contribution is one that you have recorded in your own voice (or in a voicemail at 1-833-LION-DEN)

- Contribute YOUR book recommendation for A&P teachers!

- For the complete list (and more) go to theAPprofessor.org/BookClub

Survey Says…

0.5 minute

- Please take about 5 minutes to answer some questions—it will really help improve this podcast!

Sponsored by AAA

0.5 minutes

- A searchable transcript for this episode, as well as the captioned audiogram of this episode, are sponsored by the American Association for Anatomy (AAA) at anatomy.org.

Preview | Captioned Audiogram

Regular Episode

Episode | Quick Take

Host Kevin Patton discusses the fact that mistakes in teaching anatomy & physiology happen—and that it’s okay. And how to deal with the embarrassment. Also: how stress makes our hair turn gray and a newly discovered immune lymphocyte.

00:47 | How Stress Grays Our Hair

05:16 | Sponsored by AAA

06:54 | New Type of Immune Cell

13:02 | Sponsored by HAPI

13:49 | Making Mistakes

27:23 | Sponsored by HAPS

28:08 | Survey Says…

28:34 | Staying Connected

Episode | Listen Now

Episode | Show Notes

It’s discouraging to make a mistake, but it’s humiliating when you find out you’re so unimportant that nobody noticed it. (Chuck Daly)

Stress Grays Our Hair

4.5 minutes

The leading cause of premature graying of hair in humans is teaching A&P. Not really. Perhaps. Just seeing if anybody actually reads these notes! But we do know that stress can do it. Here’s the mechanism…

- Stress speeds up hair greying process, science confirms: Fight-or-flight response nerves pump out hormone that wipes out pigmentation cells (news story) my-ap.us/3bPZ8s5

- How the stress of fight or flight turns hair white (editorial summary from Nature) https://my-ap.us/2V8Pmeo

Hyperactivation of sympathetic nerves drives depletion of melanocyte stem cells (research article from Nature) my-ap.us/2V7edPP - The five: factors that affect early greying (news feature) my-ap.us/2T5AmLI

Sponsored by AAA

1.5 minutes

- A searchable transcript for this episode, as well as the captioned audiogram of this episode, are sponsored by the American Association for Anatomy (AAA) at anatomy.org.

- Searchable transcript

- Captioned audiogram

- Don’t forget—HAPS members get a deep discount on AAA membership!

- Social Media Guidelines for Anatomists (Viewpoint commentary in Anatomical Sciences Education by Catherine M. Hennessy, Danielle F. Royer, Amanda J. Meyer, and Claire F. Smith) my-ap.us/2I3sXrv

New Type of Immune Cell

6 minutes

We know about B lymphocytes and T lymphocytes, right? What happens when we find a combination lymphocyte? A “CatDog” of lymphocytes?

- Novel Type of Immune Cell Discovered in Type 1 Diabetes Patients (news feature) my-ap.us/2v1g1iN

- A Public BCR Present in a Unique Dual-Receptor-Expressing Lymphocyte from Type 1 Diabetes Patients Encodes a Potent T Cell Autoantigen (research article from Cell) my-ap.us/2SZz453

- CatDog: The Complete Series (DVD set) amzn.to/39Og1kX

Sponsored by HAPI Online Graduate Program

1 minute

The Master of Science in Human Anatomy & Physiology Instruction—the MS-HAPI—is a graduate program for A&P teachers. A combination of science courses (enough to qualify you to teach at the college level) and courses in contemporary instructional practice, this program helps you power up your teaching. Kevin Patton is a faculty member in this program. Check it out!

Making Mistakes

13.5 minutes

MistaKes. Er, mistakes. We all make them, yet we often feel as if we shouldn’t. But it’s okay. Really. Okay.

- Another Big Year Teaching Anatomy & Physiology | Episode 62 (in which Kevin mistakenly confused the function of olfactory bulbs, then later fixed it)

- How to recover after making a mistake (self-help advice) my-ap.us/3bY3wW2

- Overcoming Imposter Syndrome (article from Harvard Business Review) my-ap.us/38Lyn63

- What It’s Like to Train Sea Lions (for fun) my-ap.us/3c3S8b8

Sponsored by HAPS

0.5 minutes

The Human Anatomy & Physiology Society (HAPS) is a sponsor of this podcast. You can help appreciate their support by clicking the link below and checking out the many resources and benefits found there. Don’t forget the HAPS Awards, which provide assistance for participating in the HAPS Annual Conference.

- Anatomy & Physiology Society

- It’s coming soon!

- Kevin’s Unofficial Guide to the HAPS Annual Conference | 2019 Edition | Episode 42

- Now is a good time to submit your questions, comments, tips, & stories for the upcoming 2020 edition!

Survey Says…

0.5 minute

- Please take about 5 minutes to answer some questions—it will really help improve this podcast!

- Yes; I’ll give you extra credit if you fill out a survey!

- theAPprofessor.org/survey

Need help accessing resources locked behind a paywall?

Check out this advice from Episode 32 to get what you need!

Episode | Captioned Audiogram

Preview | Transcript

The A&P Professor podcast (TAPP radio) episodes are made for listening, not reading. This transcript is provided for your convenience, but hey, it’s just not possible to capture the emphasis and dramatic delivery of the audio version. Or the cool theme music. Or laughs and snorts. And because it’s generated by a combo of machine and human transcription, it may not be exactly right. So I strongly recommend listening by clicking the audio player provided.

This searchable transcript is supported by the

This searchable transcript is supported by the

American Association for Anatomy.

I'm a member—maybe you should be one, too!

Topics

Kevin Patton:

Hi there, this is Kevin Patton, with a brief audio introduction to episode number 63 of the A&P Professor podcast. Also known as TAPP Radio. An audio workout for teachers of human anatomy and physiology. In the upcoming full episode, that is, episode number 63, I’m going to talk a little bit about the mechanism by which stress can make our hair gray. Now, we know that aging can cause our hair to get gray. Malnutrition can cause changes in hair color. And we also know that stress can do it. But how does stress make our hair turn gray? I’m also going to talk about a newly discovered kind of lymphocyte with an immune function that’s not a B cell and it’s not a T cell. So what is it? Well, some people call it an X cell. But exactly what it is, you’re going to have to stay tuned and find out.

Kevin Patton:

And another topic I’m going to discuss briefly is making mistakes when we’re teaching. How do we deal with that? How do we feel about that, when we make a mistake in front of a student? All that and more in the upcoming full episode, number 63.

Sponsored by HAPI Online Graduate Program

Kevin Patton:

The free distribution of this podcast is sponsored by the Master of Science in Human Anatomy and Physiology Instruction. The HAPI Degree. I’m on the faculty of this program, so I know the incredible value it is for A&P teachers. Check out this online graduate program at nycc.edu/hapi. That’s H-A-P-I. Or click the link in the show notes or episode page.

Word Dissection

Kevin Patton:

It’s time once again for word dissection, where we practice what we all do in our teaching and take apart words and translate the parts to deepen our understanding. Sometimes they’re old and familiar terms, and sometimes they’re terms that are new to us. Or maybe so fresh that they’re new to everyone. If you already have a Latin dictionary in your head, then you don’t need this review. So just skip ahead. But I need the review, so maybe the rest of you will join in with me. The first term I have on my list this time is the term, “imposter syndrome,” which clearly is not a A&P term. Not a term we typically discuss in A&P. But it’s going to relate to that idea of talking about mistakes that I mentioned a moment ago. So let’s pull it apart and see what it is.

Kevin Patton:

The first word is imposter. And when we break that down, we get the first word part, I-M, which is a variant of I-N. And that can mean the same thing as the English word in, or it could mean on. And then the second word part, P-O-S, means place, or put. So when we put those two word parts together, we have impos, or impos, and that means to put on, as in deceive. And then the O-R ending means an agent or an actor, so an imposter is someone who puts on or deceives or is fraudulent in some way. And then the part of the term syndrome, the first word part is syn, S-Y-N, and that means together. Then the second word part is drome, which is a race course or just a course of something, the path along which something progresses. And so when we put that together, it’s when we have different things that come together and are part of the same course of things.

Kevin Patton:

So we could say when we apply that to actual English usage that a syndrome is a set of signs that occur together in the course of a disease condition. So imposter syndrome means a set of characteristics that occur when you feel like you’re an imposter. Now, this term was first introduced in 1978 in an article called The Imposter Phenomenon in High Achieving Women, Dynamics and Therapeutic Intervention. That was written by two professional women, Dr. Pauline Clance and Dr. Suzanne Imes. And they defined it as an individual experience of self perceived intellectual phoniness or fraud. That is just me sort of reinterpreting what they said in their article. It’s when one thinks that even though they’ve had some success, they’re really not the expert that everyone thinks that they are.

Kevin Patton:

And even though it was first described in high achieving women, it apparently affects all groups equally at a rate of around 85% of working adults. Yeah. 85%. Yikes. I don’t know, really, because I’m not smart enough to understand, much less explain it. But I do know that it’s been very well studied and there’s a lot of different aspects and causes and so on. But it’s really important to know that it’s not a pathology. It’s just a thing that happens in the normal spectrum of human feelings. But what do I know, right?

Kevin Patton:

We’re going to be talking about this in the upcoming full episode as it relates to how we feel when we make mistakes in front of students. Or maybe we won’t talk about it, I don’t know, because I’m not sure I know enough to say anything, really. The next term that I want to talk about is norepinephrine. Now, that’s a term that we use a lot in A&P, right? But let’s break it down. Nor, N-O-R, is a chemical prefix that relates to an unbranched carbon chain. And then epi means upon, and then the nephr part, N-E-P-H-R, nephr part, that means kidney. And then I-N-E ending means a substance. So, we put that all together, and it’s a substance that has an unbranched carbon chain, and what does upon the kidney mean? Well, that’s the tissue from which it comes, is upon the kidney. That is the adrenal gland. And that is related to the term, noradrenaline, which means almost the same thing. Ad, in this case, well, we have nor, which is still that unbranched carbon chain. And then we have ad, which means toward or at, and then rene, which means kidney, and A-L means relating to. So it’s relating to something that is toward or at the kidney. So, adrenal gland. Yeah, that’s sort of like a little hat sitting on top of the kidney. Right?

Kevin Patton:

And the terms norepinephrine and noradrenaline are used interchangeably. Now, in the United States, it’s more typical to use the term norepinephrine. Outside the United States, it’s more typical to use the term noradrenaline, or noradrenaline. But they refer to the same substance. This substance is produced by fibers called adrenergic fibers. So, looking at that word, adrenergic, well, the adrenal part, we already know what that means, because we just broke that down. But the erg, or erg, E-R-G, means work. And the I-C ending means relating to. So a fiber that is adrenergic works somehow related to the adrenal gland. That is, it’s releasing a substance similar to what is released in the adrenal gland. And then melanin is a word that we use a lot in A&P, and breaking that down, we have melan, M-E-L-A-N, which means black, and then the I-N ending means substance. So a melanin means a black substance.

Kevin Patton:

Now, what’s tricky about this is that the melanins that were first given this name look black under certain lighting conditions and when packed together densely. But when you look very closely at them under sunlight, they’re actually very dark brown. So it’s kind of a misleading name, in a way. It means black stuff literally, but it should be very dark brown stuff. And what’s even more interesting about that, to me at least, is that there are two categories of melanins that we have in human skin and hair. And that is the eumelanins, and the E-U prefix that goes on eumelanin means true. So literally they are the true melanins. And what we mean by that is those are the melanins that we think of when we think of melanin. And that is this very dark brown or blackish pigment that’s found in our skin.

Kevin Patton:

The other category of melanins that we find in human skin are the pheomelanins, and that’s P-H-E-O prefix on melanin. And pheo translated literally means dusky. And this refers to melanins that have kind of a reddish tannish color to them. And they’re lighter in color than the eumelanins. So we’re going to be talking about melanin, because we’re talking about gray hair, right? That’s the absence of melanins in our hair, when our hairs turn white on our head and produce a gray look to them. But we’ll talk more about that in the full episode.

Kevin Patton:

The last thing I want to do before we leave this preview in terms of terminology is to define the acronym HLA which I’m going to be using in the preview. HLA stands for Human Leukocyte Antigen. And to oversimplify, we can think of HLAs as the cell surface proteins that are present on human cells that help regulate immune function in humans. So, keep that in mind if you’re not familiar with the term HLA, or don’t use that much in your teaching.

Sponsored by HAPS

Kevin Patton:

This podcast is sponsored by HAPS. The Human Anatomy and Physiology Society. Promoting excellence in the teaching of human anatomy and physiology for over 30 years. Go visit HAPS at theAPprofessor.org/haps. That’s H-A-P-S.

Book Club

Kevin Patton:

Hey, we have a new book club recommendation from a listener, Mike Pascoe, who’s contributed to this podcast in various ways in the past. So Mike, what do you have for us?

Mike Pascoe:

Hey Kevin. I’ve got a couple of book recommendations for you. The first is a book that is anatomically related, and that is Gulp, by Mary Roach. I believe the subtitle is, Adventures on the Alimentary Canal. So I really enjoyed this book. I really got hooked on Mary Roach after reading her book, I think most anatomists will know about, Stiff, about cadavers. And really with Adventures Along the Alimentary Canal it’s really interesting. There’s a lot of really cool topics that she unpacks by talking to scientists that do a lot of research on these really interesting questions. It’s really one of these types of books that is kind of put out there as the alimentary canal, the digestive system, digestive topics, as being a bit taboo. And things we don’t really, we’re not really encouraged to talk about.

Mike Pascoe:

But it’s a lot of fun to think about things that the book covers, like how much can you eat before your stomach bursts? Could a wine taster really tell the difference from a $10 bottle of wine to a $100 bottle? Can constipation kill you? Things like that. So it is written quite well, I really enjoyed going through it. A lot of really neat clinical correlates and pearls to include, and to add into some of my teaching. And I just recommend that folks take a look. It’s a pretty quick read, or a quick listen if you’re an audiobook subscriber.

Kevin Patton:

Well, thanks Mike. Yeah, I’m a big fan of Mary Roach’s writing, too, so I’m glad to get this book club recommendation from you. By the way, Mike mentioned that he has two recommendations. This is the first one, and you’ll hear about the second one, which is a way different kind of book, in an upcoming preview episode. In the meantime, I’ll be sending Mike his $25 Amazon gift certificate as a thank you gift for submitting his recommendation. And I’m especially grateful that he recorded it as an audio file. That’s more fun to listen to than hearing me repeat or rephrase a written message, right?

Kevin Patton:

Don’t forget, anyone who sends in a recommendation for the A&P Professor book club is eligible to receive a $25 gift certificate, just like Mike, if I use it in the A&P Professor Book Club, which you can get to at theAPprofessor.org/bookclub.

Survey Says…

Kevin Patton:

Hey, you probably forgot about that survey that I’ve been taking that’s part of my end of season debriefing. I’m asking you now to please take just a few minutes of your time to respond to that anonymous survey. Because it’s your experience as an individual listener that’s important to me. Just go to theAPprofessor.org/survey. And as always, thanks for your support.

Sponsored by AAA

Kevin Patton:

A searchable transcript and a captioned audiogram of this preview episode are funded by AAA, the American Association for Anatomy. You can find them at anatomy.org.

Staying Connected

Kevin Patton:

Well this is Kevin Patton signing off for now. And reminding you once again to keep your questions and comments coming. Why not call the podcast hotline right now, at 1-833-LION-DEN? That’s 1-833-546-6336. Or visit us at theAPprofessor.org. And I’ll see you down the road.

Episode | Transcript

The A&P Professor podcast (TAPP radio) episodes are made for listening, not reading. This transcript is provided for your convenience, but hey, it’s just not possible to capture the emphasis and dramatic delivery of the audio version. Or the cool theme music. Or laughs and snorts. And because it’s generated by a combo of machine and human transcription, it may not be exactly right. So I strongly recommend listening by clicking the audio player provided.

This searchable transcript is supported by the

This searchable transcript is supported by the

American Association for Anatomy.

I'm a member—maybe you should be one, too!

Kevin Patton:

The late basketball coach and commentator Chuck Daly one said, “It’s discouraging to make a mistake, but it’s humiliating when you find out you’re so unimportant that nobody noticed it.”

Aileen:

Welcome to the A&P Professor, a few minutes to focus on teaching human anatomy and physiology with a veteran educator and teaching mentor, your host, Kevin Patton.

Kevin Patton:

In this episode, I talk about how stress turns our hair gray, the discovery of a new type of immune cell, and making mistakes when we’re teaching.

Kevin Patton:

If you’ve met me or seen my picture, you know that I have gray hair. Well, not really gray hair. I have dark brown hairs and white hairs which I call my platinum blonde highlights. But thankfully, most folks stay a polite distance from my head and the white hairs and brown hairs mix together to produce the perception of gray.

Kevin Patton:

Now, I’m 62, so that’s not really unexpected. But I think the white hairs came just a bit earlier and in greater quantity than they might otherwise have done if not for some stressful periods in my life. No, not having to learn the Krebs cycle, not even my stint as an apprentice lion tamer. Those were more fun than stressful, but other more stressful things I coped with and thankfully survived.

Kevin Patton:

Famously, some world leaders, including US presidents, have gotten much grayer during their terms in office. Now, some of that could simply have been from timing and they’d have grayed a little bit whether they were in office or not, but now we know of a mechanism for graying of hair through stress. It involves that basic and well known story of the stress response in all it’s fight-or-flight glory.

Kevin Patton:

Here’s how we currently think it can happen. As we already know, it’s the melanocytes in the hair follicle that make the various types of reddish and brownish melanins that end up in the hair shaft. The pheomelanins and the eumelanins that produce reddish, or yellowish, or brownish, or nearly black appearances of our hair. The melanocytes come from stem cells in a part of the follicle called the bulge, which is partway up from the papilla at the bottom of the hair follicle, which is kind of weird when you think about it. Was there a Latin dictionary misplaced at the time in place that the bulge was named? What kind of anatomical name is that, bulge? But I digress.

Kevin Patton:

Getting back to the story, that bulge is full of stem cells that can and do differentiate into melanocytes. Not all of them at once, just a few of them at a time, enough that the particular hair being made gets the coloration influenced by genetics, and nutrition, and other factors. As long as there are some stem cells left behind, they can divide to make more stem cells, and therefore more melanocytes, But it’s kind of tricky. The speed of these processes has to be matched just so. Otherwise, I’ll use up all my stem cells. And darn it, I can’t make melanocytes anymore and all I can make going forward is white hairs in that follicle. Which is fine by me because it makes me look much wiser than I really am.

Kevin Patton:

It turns out that the bulge of the hair follicles receives sympathetic adrenergic fibers that release norepinephrine. The norepinephrine stimulates the conversion of more stem cells into melanocytes. That probably doesn’t affect hair color that much immediately. After all, another coat of paint isn’t going to have that dramatic of an effect.,Right? But if there’s a lot of stress responses going on over time, and therefore I release a lot of norepinephrine, then it’s possible that in some of my follicles at least I’ll convert all my stem cells into melanocytes. And that means when the current hair eventually falls out, the hair replacing it will have no melanins. It’ll be white, and I’ll be wiser, or at least look wiser.

Kevin Patton:

Searchable transcript and a captioned audiogram of this episode are funded by AAA, the American Association for Anatomy, at anatomy.org. Hey, there’s some new articles posted in the AAA journal called Anatomical Sciences Education, and I want to mention one in particular. It’s labeled as a viewpoint commentary, and it’s titled Social Media Guidelines for Anatomists. It’s written by Catherine M. Hennessy, Danielle F. Royer, Amanda J. Meyer, and Claire F. Smith. And the point they make in this commentary is a good one. That is when we represent ourselves in social media as anatomists, we ought to adhere to the professional standards of our profession. Which makes sense, right? In particular, they mention something that has come up in this podcast before, and that is using human donor specimens properly, and professionally, and respectfully. Specifically, they propose a practice of anatomists obtaining informed consent from donors before sharing cadaveric material on social media, and maybe the image should be accompanied by a statement stating that. To read the whole commentary, just go to the link in the show notes or episode page or find it at the AAA website at anatomy.org.

Kevin Patton:

I’ve said this before. Whenever I see a statement that “the textbooks will have to be rewritten if this study is true”, which I did recently, I always take notice and I look into it. This time it’s about immunity, which honestly I don’t cover very deeply in my A&P course. We do most of that in other courses in our college’s programs, so my job is to just give them some very basic ideas to go forward with. Even in my textbooks I stick with the basic ideas that will get learners started, giving them just enough to navigate the practical applications of immunity that they’ll likely encounter next.

Kevin Patton:

Okay. We all know what T cells and B cells in the immune system are, right? At least the basics. T cells are another name for T lymphocytes and B cells or another name for B lymphocytes, and we know that each population of lymphocytes have various roles in immunity, often communicating and coordinating with each other to attack antigens or cells bearing antigens, you know, bacterial cells, and cancer cells, and virus-infected cells, and so on. Except, of course, when things get messed up, maybe signals get crossed and there are immune attacks on normal healthy cells, thus producing a disease state. We call this autoimmunity because in a very simplistic way of looking at it we are attacking ourselves.

Kevin Patton:

This happens in type 1 DM, that is diabetes mellitus. In type 1 DM, helper T cells direct the killer T cells to attack the beta cells and the pancreatic islets, and that reduces insulin production. That really up our ability to maintain glucose homeostasis, which leads to all of the many damaging mechanisms of type 1 DM.

Kevin Patton:

Okay. So far nothing requiring a rewrite of any current textbooks. What’s new is that a few months ago researchers found a lymphocyte that is sort of a weird T cell/B cell sort of lymphocyte that expresses both the kinds of receptors we see on T cells and the kinds of receptors we see on B cells. It reminds me of my favorite cartoon character, CatDog. CatDog is part cat, part dog just like this cell is part T cell, part B cell, has the characteristics of both, which is pretty curious, huh? So these researchers call them DE cells, which is short for dual expressor cells or dual expressor lymphocytes. But because they’re sort of a cross of two well known lymphocyte types, they’re also sometimes called X cells are X lymphocytes. So sounding even more like a cartoon character, right? The X cell.

Kevin Patton:

Besides this discovery being both an interesting curiosity and a necessary tool for preventing us from ever thinking that we have the human body completely figured out, it also helps us understand type 1 DM better. Why? Well, it turns out that the B cell receptors on these weird X cells include a special peptide that is not normally found among the highly varied receptors on typical B cells. And that weird receptor can very, very, very strongly bind … Wait a minute. That’s three verys. It can very, very, very strongly bind to an HLA called HLA-DQ8, which is thought to present insulin to T cells and thus trigger an attack. Because that binds so strongly, remember three verys, so strongly, the likelihood of triggering an anti-insulin attack is that much more likely than just a small, random skirmish that may not end up producing a disease state at all. But when these weird X cells are around with their particular form of B cell receptor acting like helper T cells by triggering killer T cells to attack insulin, well, then it’s a full on war, and that war progresses beyond attacking the hormone to also attack the pancreatic beta cells making the insulin.

Kevin Patton:

The researchers telling this new version of the story think this is just the beginning stages of type 1 DM. And their discoveries, if they pan out to be accurate in the long run, could give us a way to watch for and monitor the onset of type 1 DM, something we can’t really do right now. But there really are a lot more questions here than potential answers. Besides some holes in a more detailed version of the story that still need filling in, there’s the question of, well, where these X cells come from and how they develop. I mean, we know a lot about T cells and B cells and they’re even named for where they develop, but we don’t know that about these X cells. So nah, not ready for textbooks yet, nor for our A&P course. Except, I think it might be an interesting aside to share with students if the occasion permits to let them know that there’s still a lot to learn about human anatomy and physiology.

Kevin Patton:

The free distribution of this podcast is sponsored by the Master of Science in Human Anatomy & Physiology Instruction, the HAPI degree. As educators, I wonder if we always value education as highly as we think we do. How many of us stop taking courses after we get that last degree? We head off into teaching often without having any kind of degree or certificate in teaching. Hmm, I wonder if we’re being the best we can be with this mindset. Why don’t you check out this online graduate program at nycc.edu/HAPI, that’s H-A-P-I, or click the link in the show notes or episode page.

Kevin Patton:

This segment is all about making mistakes. I listen to a few podcasts that typically end with a so-called blooper reel in which outtakes or mistakes that have been edited out of the body of the podcast are played as a sort of comical diversion. I don’t do that. It’s not because I don’t make mistakes. I make more than my share of them, but I just cut them out as I’m doing my editing. It never really occurs to me in the rush to get it all done that I should do anything other than delete them. Sorry about that. If you really love to hear bloopers, you’re not going to. Trust me, my mistakes are just sad. They’re not funny. Well, okay, sometimes they are funny. I actually laugh at them when I make them, but I never really think about preserving while I’m making my mad dash through the editing process.

Kevin Patton:

Sometimes my mistakes actually make it out into the airwaves. Like in the last episode in which I recounted a previous episode in which I marveled at the examples of how people with no visible olfactory bulb could still sense odors okay. Except that I stated, and stated consistently several times, that they could hear despite having the lack of both olfactory bulbs. Despite it being a huge mistake about a very basic idea, I didn’t catch it as I said it, nor when I edited the segment, nor when I listened to the processed sound file, nor when I played it the first time in the podcast player just to make sure that it all got out there okay with the correct episode’s file and all that. It wasn’t until I let it restart and play in the background did I notice a mistake. And I hardly ever let it play in the background, but for some reason I did for the last episode. It’s a good thing.

Kevin Patton:

So once I caught it, I fixed it in the sound clip for that segment, redid all my processing steps, and then republished it before very many of them had been downloaded by listeners. Maybe you’re one of the lucky few that has that rare copy downloaded that has me saying the wrong thing. You ought to say that because someday it’s going to be … No, it’s not ever going to be worth any money. Don’t save it. Please don’t save my mistake and preserve it, okay?

Kevin Patton:

Like any of you, I make mistakes in my teaching, my writing, and, well, in just about everything I do professionally. In my early career. It kind of shocked me that I never stopped making mistakes, not the same ones generally. But I had this weird notion that mistakes stop happening once a person has reached a certain level of training and had some experience and success in their profession. Yet here I was making it relatively unscathed through several advanced degrees and becoming very successful in teaching, writing, speaking, and academic leadership and yet still making mistakes. And the more visible and audible my work became, the more people could see my mistakes.

Kevin Patton:

I think that early on I was probably developing what some folks call the imposter syndrome, which I explained a bit in the word dissection part of the preview episode that precedes this full episode. It’s not a pathology but a way of thinking that was first identified in successful professionals back in the late 1970s. Put simply, it’s when a person doubts one’s own accomplishments and feels somewhat of a fraud in living the life of an expert. It apparently happens a lot in academia because, well, we’re professional experts, right? Paid to teach and to profess our expertise.

Kevin Patton:

Depending on a huge variety of wildly different factors, we could feel guilty about not being perfect. And when we are acknowledged for our success or our expertise, we could feel that we’re somehow pulling something over on everyone. The thinking behind the so-called imposter syndrome or other similar mindsets can be dangerous in many ways, not the least of which is not valuing mistakes. Yeah, mistakes are extremely valuable. I’ll circle back to that notion in a minute, but first I want to say that whether they’re valuable, or worthless, or a liability doesn’t really change the fact that we’re going to make mistakes. So of nature, right?

Kevin Patton:

Lucky for me, I learned that lesson early. And over the course of decades, I think I’ve learned to live with, and sometimes, not always, but sometimes value my mistakes. When I do value them, or at least don’t dwell on them, thus letting them generate anxiety and guilt, I’m a lot happier person, a more productive professional, and in some ways better off for those mistakes, the ones that don’t actually harm me or others, but sometimes even those.

Kevin Patton:

The reason I bring this up is that recently I’ve heard and overheard remarks from my peers about mistakes they’ve made or mistakes they fear making, remarks like, “How can we hold our students to a standard when we ourselves sometimes slip up and fall short of that standard?” Now, my first thought when I hear these things is, “Yep. Right? I feel your pain.” But my next thought often goes right back to those mentors I’ve had who’ve helped me look at these things in a different way, a way that is more realistic, and more self-accepting, and also more productive and useful it turns out. And yes, once again, I have some stories from the olden days from early lessons from my mentors. One story is from my wild animal training days.

Kevin Patton:

Before I was an apprentice lion tamer, I was an apprentice sea lion trainer. My mentor, Jim Alexander, was and is a serious student of wild animal training, and he taught me a lot. One lesson occurred after we’d both gone to see an educational demonstration that featured trained wild animals. It was phenomenal. As usual, Jim used Socratic questioning afterward to make sure I learned something from the experience. He asked if I noticed any mistakes in the behaviors in the show. At first, I couldn’t think of any. Then with some prompting, I remembered some pretty big flubs where an animal didn’t do what they’d been trained to do. And he said, “But it seemed like it went extremely well overall, right?” Yeah. Well, he eventually got me to see that the trainer’s reaction to the mistake was the key. Unlike some other trainers we’d seen together who’d get flustered when mistakes occurred, this trainer acted amused by the mistakes. He laughed them off and carried on with a cheerful demeanor.

Kevin Patton:

Jim pointed out that mistakes always happen, even if you and the animals are well prepared, and you have to have a strategy to deal with that. Not letting it upset you, he pointed out, is the best strategy, or at least acting like it’s not upsetting you, to seem as if it’s all part of the fun. And he pointed out when you do that, it actually does become part of the fun and the flustered feeling really can dissipate. He also pointed out that some of the mistakes we saw were turned into moments of laughter. He mused that the trainer was likely to even try to mold that mistake into a new and amusing behavior.

Kevin Patton:

It turns out that not long after that I was training a new sea lion for our show and would bring her out before showtime to both get her used to crowds and to show people how animals are trained. I was trying to get Yvonne the sea lion to catch some rings that I was tossing to her. She was really good at it and was quickly becoming an expert. But all that practice, practice, practice didn’t seem to help my pitching arm very much. And during a pre-show training demo where I had several friends in the audience who’d never seen me perform with animals, I threw a wild pitch that Yvonne could not possibly catch and the audience winced. I probably did too. A mistake in front of a crowd, including some friends that I wanted to impress. Well, almost immediately, Yvonne, anticipating a potential reduction in fish snacks, ran over to the ring, and grabbed it in her mouth, threw it up in the air, and caught it around her neck like she was supposed to. Phew! I remembered my lesson from Jim, and I laughed it off. And from that day forward, that last ring being missed became part of the act. Far more entertaining than the original behavior, and far more enriching for the animal.

Kevin Patton:

I know it’s sort of a cliché to say we should look at mistakes as opportunities. But once I really started experiencing that, it started to become a habit, and I’ve gotten a bit better at it. Not yet a master, but better. And at the very least, it’s saved me some frustration and self-doubt that I’d have otherwised experience. Of course, as we get better at particular skills, we make fewer mistakes. And that’s our goal, right? And if we try new things, well, it’s just expected that we’re going to have pretty many mistakes until we settled in. Or maybe just decide to abandon that new thing and try something different.

Kevin Patton:

If we let these kinds of mistakes get us down, it’s going to damage us little by little. These kinds of mistakes are learning opportunities and not reflections of our overall competence or worth. But that cliché of mistakes being potential opportunities, even though true, is not really the point I want to share today. Really what I’m trying to get at in my idiosyncratic meandering way is that it’s okay, really, okay to make mistakes sometimes, mistakes in teaching, mistakes in writing, mistakes in helping students. We all make them, not just beginners but even those who’ve been doing this for a long, long time.

Kevin Patton:

Making occasional mistakes is a sign of humanity, a sign of being human, not a sign of weakness, incompetence, or any level of worthlessness. It’s not that we should strive to never have feelings of failure, or guilt, or embarrassment, it’s that it’s okay to make mistakes and have those embarrassed feelings but still not see it as a negation of our professional expertise or our personal worth. Beyond that, though, is the lesson that our students will learn if we can face our mistakes in our courses with grace and humility, perhaps even with some amusement, and show students how true professionals can accept mistakes, even express some dismay and still keep going, working to avoid future mistakes but not being done in by the fact that we do make mistakes, and sometimes even make them in public. This lesson of not taking ourselves too seriously may in the long run be much more valuable towards students than knowing the role of olfactory bulbs in smell, or hearing, or taste, or whatever. I don’t know. What is it again?

Kevin Patton:

Marketing support for this podcast is provided by HAPS, the Human Anatomy & Physiology Society, promoting excellence in the teaching of human anatomy and physiology for over 30 years. Go visit HAPS at theAPprofessor.org/haps. That’s H-A-P-S. I think a lot of HAPS members don’t think much about the one-day regional HAPS meetings that occur on weekends at various times of the year and various locations around North America. Hey, maybe today’s a good day to go to theAPprofessor.org/haps and check out the full list of regional meanings.

Kevin Patton:

Hey, you probably forgot about that survey that I’ve been taking. I’m asking you now to please take just a few minutes of your time to respond to that anonymous survey because it’s your experience as an individual listener that’s important to me. Just go to theAPprofessor.org/survey. And as always, thanks for your support

Kevin Patton:

Hey, don’t forget that I always put links in the show notes and the episode page at theAPprofessor.org in case you want to further explore any ideas mentioned in this podcast or if you want to visit our sponsors. And you’re always encouraged to call in with your questions, comments, and ideas at the podcast hotline. That’s 1-833-LION-DEN or 1-833-546-6336. Or send a recording or written message to podcast@theAPprofessor.org. I’ll see you down the road.

Aileen:

The A&P Professor is hosted by Dr. Kevin Patton, an award-winning professor and textbook author in human anatomy and physiology.

Kevin Patton:

This episode should be taken once daily with food.

This podcast is sponsored by the

Human Anatomy & Physiology Society

This podcast is sponsored by the

Master of Science in

Human Anatomy & Physiology Instruction

Transcripts & captions supported by

The American Association for Anatomy.

Stay Connected

The easiest way to keep up with new episodes is, um, wherever you already listen to audio!

Click here to be notified by email when new episodes become available (make sure The A&P Professor option is checked).

Call in

Record your question or share an idea and I may use it in a future podcast!

Toll-free: 1·833·LION·DEN (1·833·546·6336)

Email: podcast@theAPprofessor.org

Share

Tools & Resources

TAPP Science & Education Updates (free)

TextExpander (paste snippets)

Krisp Free Noise-Cancelling App

Snagit & Camtasia (media tools)

Rev.com ($10 off transcriptions, captions)

The A&P Professor Logo Items

(Compensation may be received)

🏅 NOTE: TAPP ed badges and certificates can be claimed until the end of 2025. After that, they remain valid, but no additional credentials can be claimed. This results from the free tier of Canvas Credentials shutting down (and lowest paid tier is far, far away from a cost-effective rate for our level of usage). For more information, visit TAPP ed at theAPprofessor.org/education

2 comments

Kevin, the Dr. Silkstone Mysteries might be of interest.

https://www.goodreads.com/series/175204-dr-thomas-silkstone

oooh, those look good, David! Got a couple of sentences you could share with listeners when I put these in the Book Club?