More Flashcards: Hidden Powers Unleashed

TAPP Radio Episode 59

Preview Episode

Preview | Quick Take

A brief preview of the upcoming full episode , featuring upcoming topics (more flashcards, pseudogenes, survey) —plus word dissections, a book club recommendation (Anatomists and Eponyms), and more!

00:19 | Topics

01:92 | Sponsored by HAPI Online Graduate Program

01:56 | Word Dissection

09:04 | Sponsored by HAPS

10:18 | Book Club

13:12 | Sponsored by AAA

13:54 | Survey Says…

15:09 | Staying Connected

Preview | Listen Now

Preview | Show Notes

Upcoming Topics

1 minute

- Pseudogenes

- Getting to sleep

- More Flashcards: Hidden Powers Unleashed

- First listen to Flashcards: Hidden Powers | Episode 58

Sponsored by HAPI Online Graduate Program

0.5 minute

The Master of Science in Human Anatomy & Physiology Instruction—the MS-HAPI—is a graduate program for A&P teachers. A combination of science courses (enough to qualify you to teach at the college level) and courses in contemporary instructional practice, this program helps you power up your teaching. Kevin Patton is a faculty member in this program. Check it out!

Word Dissection

7 minutes

- obverse

- reverse

- mnemonic

- pneumonic

- pseudogene

Sponsored by HAPS

1 minute

The Human Anatomy & Physiology Society (HAPS) is a sponsor of this podcast. You can help appreciate their support by clicking the link below and checking out the many resources and benefits found there. Don’t forget the HAPS Awards, which provide assistance for participating in the HAPS Annual Conference.

Book Club

2.5 minutes

- Anatomists and Eponyms: The Spirit of Anatomy Past

- by Kurt Ogden Gilliland & Royce Montgomery

- amzn.to/2PJe9ms

- The Eponym Episode | Using Modern Terminology | Episode 40

- More on Eponyms in A&P Terminology | Episode 41

- Special opportunity

- Contribute YOUR book recommendation for A&P teachers!

- Be sure include your reasons for recommending it

- Any contribution used will receive a $25 gift certificate

- The best contribution is one that you have recorded in your own voice (or in a voicemail at 1-833-LION-DEN)

- Check out The A&P Professor Book Club

- Contribute YOUR book recommendation for A&P teachers!

Sponsored by AAA

0.5 minutes

- A searchable transcript for this episode, as well as the captioned audiogram of this episode, are sponsored by the American Association for Anatomy (AAA) at anatomy.org.

Survey Says…

1 minute

- Please take about 5 minutes to answer some questions—it will really help improve this podcast!

Preview | Captioned Audiogram

Regular Episode

Episode | Quick Take

Second of three episodes about flashcards reveals more behind the use of this tool for learning anatomy & physiology. The term pseudogene may cause problems. A junk-DNA analogy. Bonus track: Delta Wave Radio Hour.

00:47 | Pseudogenes

08:10 | Sponsored by AAA

08:49 | Pseudogene Analogy

12:35 | Sponsored by HAPI

13:18 | Need Some Sleep?

18:20 | Sponsored by HAPS

19:08 | Flashcards Again

28:16 | Survey Says…

29:21 | Flashcard Learning Tricks

43:05 | More Flashcards

34:31 | Staying Connected

46:26 | Delta Wave Radio Hour (BONUS)

Episode | Listen Now

Episode | Show Notes

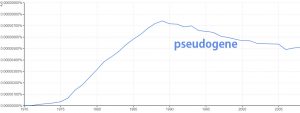

Pseudogenes

7.5 minutes

Are we doing our students the best service by emphasizing the classic definition of a pseudogene as a gene “without function?” Discuss.

- Pseudogene word dissection found in Preview Episode 59

- Overcoming challenges and dogmas to understand the functions of pseudogenes (journal perspective article from Nature Reviews Genetics) my-ap.us/2PMX3DW

- A pseudogene structure in 5S DNA of Xenopus laevis (research article in Cell using “pseudogene” for the first time) my-ap.us/2ZfqW2R

- Pseudogene use history in books (from Google Ngram Viewer) my-ap.us/2Q6UdJ7

- Improbable Destinies: Fate, Chance, and the Future of Evolution by Jonathan B. Losos

- amzn.to/2L9fzCE

- Browse The A&P Professor Book Club https://theapprofessor.org/bookclub.html

- amzn.to/2L9fzCE

Sponsored by AAA

0.5 minutes

- A searchable transcript for this episode, as well as the captioned audiogram of this episode, are sponsored by the American Association for Anatomy (AAA) at anatomy.org.

Pseudogene Analogy

3.5 minutes

- Junk DNA, or pseudogenes, is a rather abstract concept for beginning learners, so perhaps an analogy is in order.

Sponsored by HAPI Online Graduate Program

0.5 minute

The Master of Science in Human Anatomy & Physiology Instruction—the MS-HAPI—is a graduate program for A&P teachers. A combination of science courses (enough to qualify you to teach at the college level) and courses in contemporary instructional practice, this program helps you power up your teaching. Kevin Patton is a faculty member in this program. Check it out!

Need Some Sleep?

5 minutes

Sleep science suggests that podcasts can be useful in helping us fall asleep. This podcast may be especially useful as a safe and effective sleep aid. Listen to this segment to find out why. If you can stay awake for it.

- Science Supports Your Habit of Falling Asleep to Stupid Podcasts (feature health article) my-ap.us/34GOajz

- The influence of white noise on sleep in subjects exposed to ICU noise (study of white noise to help induce sleep) my-ap.us/34MF8BR

- Sleep With Me (podcast specifically for sleep inducement) my-ap.us/35LPKST

- Sleep Headphones Wireless, Perytong Bluetooth Sports Headband Headphones with Ultra-Thin HD Stereo Speakers Perfect for Sleeping,Workout,Jogging,Yoga,Insomnia, Air Travel, Meditation amzn.to/36W3p9W

Sponsored by HAPS

1 minute

The Human Anatomy & Physiology Society (HAPS) is a sponsor of this podcast. You can help appreciate their support by clicking the link below and checking out the many resources and benefits found there. Don’t forget the HAPS Awards, which provide assistance for participating in the HAPS Annual Conference.

Flashcards Again

9 minutes

- Part of our role as teachers is to be learning therapists who help our students diagnose barriers to learning and then develop effective treatment plans to become better learners.

- Flashcards: Hidden Powers | Episode 58

Survey Says…

1 minute

- Please take about 5 minutes to answer some questions—it will really help improve this podcast!

Flashcard Learning Tricks

13.5 minutes

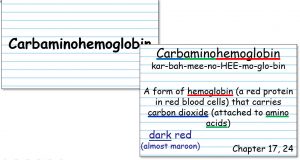

- Building on Flashcards: Hidden Powers | Episode 58, Kevin discusses using images, color coding, the beauty of plaid flashcards (ahem), and the layering (interleaving) effect.

- Six a Day (blog article for A&P students) my-ap.us/2Z4Y5OV

- Learn how to Study Using… Retrieval Practice (blog article for any student) my-ap.us/35GW5Ph

More Flashcards

1.5 minutes

- Yep, there’s more about flashcards coming in the third part of this series. Check out Episode 60 when the time comes.

- As promised, I reveal the secret of the levitating flashcard. But the only way to access this video is by using the TAPP app, where the bonus video resides.

- Plays episodes of this podcast

- Plus bonus material (PDF hanounds, images, videos)

- Free of charge

-

- Lots of great features and functionality

- Easy way to share this podcast

- Even folks who don’t know how to access a podcast can download an app

- Getting the TAPP app

- Search “The A&P Professor” in your device’s app store

- iOS devices: my-ap.us/TAPPiOS

- Android devices: my-ap.us/TAPPandroid

- Kindle Fire: amzn.to/2rR7HNG

Delta Wave Radio Hour (BONUS track)

6.5 minutes

- Need to fall asleep fast? Listen to Dr. ZZzzz drone on about Influenza, using information from the CDC, in this popular fictional podcast.

- Please do not drive or operate machinery while listening to this bonus track after the episode close.

- Dedicated to Dic and Ellen.

Need help accessing resources locked behind a paywall?

Check out this advice from Episode 32 to get what you need!

Episode | Captioned Audiogram

Preview | Transcript

The A&P Professor podcast (TAPP radio) episodes are made for listening, not reading. This transcript is provided for your convenience, but hey, it’s just not possible to capture the emphasis and dramatic delivery of the audio version. Or the cool theme music. Or laughs and snorts. And because it’s generated by a combo of machine and human transcription, it may not be exactly right. So I strongly recommend listening by clicking the audio player provided.

This searchable transcript is supported by the

This searchable transcript is supported by the

American Association for Anatomy.

I'm a member—maybe you should be one, too!

Introduction

Hi there. This is Kevin Patton with a brief audio introduction to episode number 59 of The A&P Professor podcast, also known as TAPP Radio, a virtual salon for teachers of human anatomy and physiology.

Topics

Kevin Patton:

In the upcoming full episode, that is episode number 59, we’re going to be covering pseudogenes and why that name pseudogene may be problematic. I’m also going to talk about how to treat insomnia with what you already have with you at this very moment. I’ll keep you guessing for a few days. And the featured topic in episode number 59 is going to be a continuation of our conversation about flashcards, especially the hidden powers of flashcards and extra bells and whistles that we can use or that our students can use to help them in their learning process. All that and more coming up in episode number 59.

Sponsored by HAPI Online Graduate Program

Kevin Patton:

Free distribution of this podcast is sponsored by the Master of Science in Human Anatomy & Physiology Instruction. The HAPI degree. This isn’t like a typical master’s degree. This one is designed for folks who already have a related advanced degree, like a master’s or a doctorate, and want to even out their science background while they learn more about the art and science of teaching. Check out this online graduate program at nycc.edu/HAPI. That’s HAPI. Or click the link in the show notes or episode page. There’s always a new cohort forming, so now’s a good time to check it out. Maybe it could be part of your New Year’s resolution.

Word Dissection

Kevin Patton:

You know it. It’s time once again for word dissection where we practice what we all do in our teaching and take apart words and translate their parts to deepen our understanding. Sometimes they’re old and familiar terms and sometimes they’re terms that are new to us or maybe so fresh that they’re new to everyone.

The first word on today’s list is obverse. And it goes along with another term we’re going to cover, and that is reverse. When we break apart obverse, the first part, ob, O-B, means toward in this case. And verse, that word part means turn. So literally, it’s turn toward. So when we apply it to something with two surfaces, like a coin, or a flag, or a flashcard, then the surface of the card that is turned toward us, that is the front or principle surface, then that’s the obverse. Now looking at the opposite word, reverse, that word part re means back. Literally, it means again. But in this case, it means back. So we can take it to mean turn back. Reverse, turn back.

So, the term reverse usually refers to the back or rear surface of anything, like a coin, or a flag, or a flashcard. So when we’re looking at our flashcard, the surface that is facing us at first it’s called the obverse side. And then when we flip it over, what we see on that side we’re seeing on the reverse side. So we’re going to be talking about flashcards, and I’m going to be throwing out the terms are obverse and reverse, so I just want to kind of remind us of that. And of course, it’s a deeper dive than we usually take with ordinary terms, right?

The next word on our list is mnemonic. Now there’s another term that we’ve all heard before and used ourselves with our students. We kind of broke it down in episode number 45, but it wasn’t part of a regular word dissection, so let’s kind of review that now. The first part, the M-N-E, and actually the whole main part of the word, M-N-E-M-O-N, mnemon, that means memory. Literally, it can be sort of translated as mindful, but we usually use it in the sense of memory. Then, the I-C ending we’ve seen a zillion times before, and that is relating to. So if something is mnemonic, it’s relating to mnemon, that is to memory, so it’s memory related, and that’s all it means. But, we usually use it to refer to something that aids our memory, that is a memory assistance mechanism of some sort.

Now, it can be a mnemonic sentence or phrase where the first letter of each word in the mnemonic sentence has the same first letter of items in a list that we want to memorize. But anything that helps us remember is actually a mnemonic. So it could be just a mental image of something to help remember somebody’s name, or where something’s located, or where we left our keys, or whatever. That is a mnemonic. So, it’s actually much broader than we often use it.

Another thing about the word mnemonic is it is often mispronounced, and it’s often also misspelled as pneumonic. Now, the actual word pneumonic, which is different than mnemonic, pneumonic, is spelled P-N-E-U-M-O-N-I-C, and we use that in A&P a lot, too, or at least a little bit. It comes from the word part pneumon, which means lung. We see that in a lot of terms that we’re ready familiar with, like pneumonia, pneumothorax, pneumonic plague. Then, of course, the I-C ending means relating to. So if something is pneumonic, it’s relating to the lung. So if you say, “Well, here’s a pneumonic sentence that helps us remember the 12 classic cranial nerves,” that doesn’t really make much sense. Here’s something lung related that’s going to help us remember the cranial nerves? What? But, of course, because they’re so similar in their sound, they’re very easily confused. So, we might have learned that from someone. Maybe that was our initial learning where someone told us it’s pneumonic. It’s a pneumonic device. So, it could be that.

Or sometimes, and this happens to me a lot, I’ll know the correct pronunciation, I’ll know the correct word, but that’s not what comes out of my mouth. I don’t know why. Because maybe I’m just more used to saying that other term that I don’t really mean at that point. I don’t know. But, that is something to watch out for because it does kind of affect our credibility when we’re dealing with students. If we’re always using the wrong word for something, eh, that can kind of ding how we come across as professionals. And I don’t know. If you’re like me, I just kind of, if I can be right, I want to be right in terms of proper use of terminology. So, that’s mnemonic and also pneumonic, two different words that sound alike.

And the last word on our list is pseudogene. That’s easy to break apart, right? Pseudo we know means false. Gene, well, it literally means create or beget, but here it refers to a unit of genetic code, a gene that’s inherited by each generation of cells or organisms and used to guide cell structure and function. Now, pseudogene is often defined as a unit of DNA that resembles a gene but with no genetic function. It’s often buried within the code of an actual working functioning gene. Now, some biologists define pseudogenes as broken or defective genes or groups of genes. The term junk DNA has also been used to describe them.

The National Cancer Institute’s dictionary of genetic terms defines pseudogene as a DNA sequence that resembles a gene but has been mutated into an inactive form over the course of evolution. It often lacks introns and other essential DNA sequences necessary for function. Though genetically similar to the original functional gene, pseudogenes do not result in functional proteins, although some may have regulatory effects. And that last statement in the definition from National Cancer Institute is important because that’s going to be the opening of a doorway that we’re going to walk through when we get to the full episode and talk about a recent article about pseudogenes.

Sponsored by HAPS

Kevin Patton:

This podcast is sponsored by HAPS, the Human Anatomy & Physiology Society, promoting excellence in the teaching of human anatomy and physiology for over 30 years. Hey, if you’re thinking about going to the HAPS annual conference next May in Ottawa, and why wouldn’t you be thinking about that, don’t forget that you have until February 21st to claim an early bird discount on the registration fee. Now, please know one need not be a bird or even a birder to claim the early bird discount. But I have noticed that a lot of birders do claim the discount. Maybe because the prices are cheap. I know. Those bird puns are hard to swallow, right? They’re so foul. I don’t know. I think a good bird pun can be a real hoot. Okay, I’ll stop. I don’t want you to egret listening, do I? By the way, February 21st is the same deadline for workshop and poster proposals. Go visit HAPS at theAPprofessor.org/HAPS. That’s HAPS.

Book Club

Kevin Patton:

I have a new recommendation from The A&P Professor Book Club for you. It’s called Anatomists and Eponyms: The Spirit of Anatomy Past. This little book is not very big. But when you start to skim through it, and I’m telling you, you are going to start skimming through it after you pick it up, you’ll be impressed with how much is inside this little book. It’s one of those books you pick up in a bookshop to glance inside and a half hour later you find yourself still standing in the same spot and checking your watch to see if you have more time to spend exploring through the book.

Anatomists and Eponyms: The Spirit of Anatomy Past starts out with a brief explanation of what eponyms are and their role in scientific and medical terminology. And then there’s a brief synopsis of the history of anatomy through the ages. But, the main part of the book looks at the anatomists who lent their name to body structures, organized by systems of the body. Although that initial history synopsis is brief, I think it’s important.

I always kick off my A&P course with a similar story, so I like hearing someone else’s take on it. Doing that makes my story better. I think it also helps students understand how we got to where we are, as well as the cultural factors that will continue to influence how we do human biology into the future. But back to the main part of the book, the scientists behind the eponyms, all I can say is try to stop. I dare you. Each brief entry, which is also illustrated, is fascinating because it brings us face to face with the people behind the names. We now know what they look like, at least in some cases, who they were, and some interesting tidbits of information about their lives and their work. Because each entry is brief and also interesting, we just naturally want to move to the next one because, well, it only takes a couple of minutes to read the next one. It’s like french fries. Just one more won’t make any difference, right? Pretty soon, the whole supersize bowl of fries is gone.

This is both a fun read-through the first time and a useful tool to pull off the bookshelf from time to time as you’re teaching A&P. Check out Anatomists and Eponyms: The Spirit of Anatomy Past as well as other books of interest to A&P teachers at theAPprofessor.org/bookclub.

Sponsored by AAA

Kevin Patton:

The searchable transcript and a captioned audiogram of this preview episode are funded by AAA, the American Association for Anatomy. I’ve been surfing around the new website at anatomy.org, and I think it’s more engaging and easy to use than ever. But what’s really fun is discovering all the kinds of resources and activities of AAA, some of which I never knew about. Or maybe I just forgot. Anyway, I recommend checking out anatomy.org right now and consider being part of this dynamic and evolving organization.

Survey Says…

Kevin Patton:

I’m going to be reminding you about this in the full episode, but I want to mention it now. And that is that as we wind up the second full year of The A&P Professor podcast, it’s a good time for reflection. And you may recall that way back in episode 17 I advocated that we all do debriefings or reflections at the end of each academic year, so it’s really not very surprising that I’m doing that now with this podcast.

Now, part of that process for me this year is gathering feedback from you. So I’m asking you for about five minutes of your time to fill out a survey. It’s put together by a team of specialists to help me tweak and improve things. No matter if you’re a new listener or a long-time listener, whether you’ve listened to just one episode or even just part of an episode, or maybe you’ve listened to all the episodes, I don’t know, I’d really appreciate your time to respond to the anonymous survey. Just go to theAPprofessor.org/survey.

Staying Connected

Kevin Patton:

Well, this is Kevin Patton signing off for now and reminding you to keep your questions and comments coming. Why not call the podcast hotline right now at 1-833-LION-DEN? That’s 1-833-546-6336. Or visit us at theAPprofessor.org. I’ll see you down the road.

This preview episode is sponsored by the American Association of Anatomists, the Human Anatomy & Physiology Society, and the Master of Science in Human Anatomy & Physiology Instruction

Episode | Transcript

The A&P Professor podcast (TAPP radio) episodes are made for listening, not reading. This transcript is provided for your convenience, but hey, it’s just not possible to capture the emphasis and dramatic delivery of the audio version. Or the cool theme music. Or laughs and snorts. And because it’s generated by a combo of machine and human transcription, it may not be exactly right. So I strongly recommend listening by clicking the audio player provided.

This searchable transcript is supported by the

This searchable transcript is supported by the

American Association for Anatomy.

I'm a member—maybe you should be one, too!

Kevin Patton: Part of our role as teachers is to be learning therapists who help our students diagnose barriers to learning and then develop effective treatment plans to become better learners.

Aileen: Welcome to The A&P Professor, a few minutes to focus on teaching human anatomy and physiology with a veteran educator and teaching mentor; your host Kevin Patton.

Kevin Patton: In this episode, I talk about pseudogenes. The relationship of podcasts and sleep and I continue with part two of our discussion of flashcards. Way back in the olden days specifically 1977, that’s when I was a college freshman, so yes indeed, it was the very olden days. There were three scientists in Europe. Their names were Jacq, Miller, and Brownlee; and they proposed the term pseudo gene for a sequence of repetitions of about 700 base pairs in the 5S RNA gene of African clawed frogs that are not really part of the functioning gene. These scientists suggested that the pseudogenes were probably evolutionary leftovers and they have no function. Over the decade since then, many more pseudogenes have been discovered. At the last count, there were somewhere around 10,000 of them that have been identified.

Kevin Patton: A common working definition these days is that a pseudogene is a region of the genome that contains one or more defective copies of a gene. The name pseudogene, which I remember we went over in the Word dissection segment of the preview episode number 59 right before this full episode. Then we said that it literally means false gene. That seems to fit pretty well, right? It’s like a gene, but it doesn’t work. Yeah. It’s a false gene. Good name, right? Yeah. Well, it turns out maybe not so much. I guess that’s a risky run when you’re the first to name something. After all your discovery is well, new and there hasn’t been a lot of time and effort put into multiple studies and multiple applications of this new discovery that you just made.

Kevin Patton: You don’t have the benefit of hindsight because that can only happen in the future. Here you are in the present, nor do you have access to all those amazing new technologies that are yet to be invented. Then later on, your carefully crafted new term may turn to be misleading or perhaps even false. It’s ironic that a recently published perspective article in Nature Reviews Genetics suggests that the term pseudogene may be, well, false. That is pseudogenes may really be doing something and maybe they aren’t functionless. It’s not false at all, at least in terms of whether it has a function or not.

Kevin Patton: The authors of this new perspective aren’t just trying to play a gotcha game with their article. If the original hypothesis of no function for pseudogenes had turned out to be true, then it would have turned out to have been a great name. As it turns out, it’s not true that all of these odd regions of the genome don’t do anything. Well. Okay. That’s somewhat arguable. Functioning pseudogenes may not have the obvious and direct functions that true genes do, but this perspective articles suggest that maybe we should stop thinking of them as entirely functionless. Some pseudogenes function by influencing chromatin structure in ways that regulate gene expression.

Kevin Patton: There are other pseudogenes that play a role in some human diseases. One of the first functions of pseudogenes ever discovered involves inhibition of the gene for neural nitric oxide synthase in snails. In this perspective article, they have a table of a whole bunch of different pseudogenes and what their functions are. Another of the many things that the authors bring up in this perspective article is the possibility that pseudogenes may be a repository of genetic information that may add the genetic redundancy and resilience needed for evolution. They give the example of 36 human protein coding genes that were formed from pseudogenes. At least we think they were formed from pseudogenes during evolution after we diverged from other primates.

Kevin Patton: Now all this talk about evolution reminds me, don’t forget that book I recommended back in the preview episode number 32 written by my friend Jonathan Losos. It’s titled Improbable Destinies, Fate, Chance in the Future of Evolution. You might want to move that book up a little bit higher on your reading list. It’s a great set of stories that lay out some really cool contemporary ideas about how evolution works. Getting back to this perspective article on pseudogenes. A main point that this article is trying to make is that the term pseudogene may be misleading and that pseudo part may also give a negative connotation. Yeah. False. I mean that’s negative, right? False. That’s almost literally negative. It’s not only misleading, but it has this negative connotation.

Kevin Patton: Both of those aspects have probably already slowed or delayed the start of intense investigation of pseudogenes. Why waste time and effort on things that are false and functionless after all? I think that as an A&P teacher, I had to be careful when I talked to my students about pseudogenes. If I use a classic definition that emphasizes their lack of function; am I unintentionally setting up a barrier for my students? I mean, if we’re discovering various functions of pseudogenes; some of which may turn out to be central to processes my students will be dealing with in the future. Want to be easier for them to understand if I start them out with a broader, more accurate concept of the pseudogene.

Kevin Patton: Now I have a link in the show notes and the episode page at theapprofessor.org/59 that links to this article. I recommend you read it. It’s not very long because you want to both learn some facts about what we know about pseudogenes and what we don’t know about pseudogenes, and to consider the interesting arguments that the authors are making. By the way, they don’t really come out and suggest an alternate name. Maybe they’re afraid of coming up with the wrong name that it’s going to be attacked or argued against in some later decade. I don’t know, but it seems to me that their main purpose is to state that this is a discussion worth having. Isn’t that great when we do that in science? I just love the way science works. Don’t you?

Kevin Patton: A searchable transcript and a captioned audiogram of this episode are funded by AAA, the American Association for Anatomy at anatomy.org. Did you know that if you’re already a member of HAPS, you can get a deeply discounted membership rate with AAA? Now’s a great time to join too with all kinds of new and exciting resources and activities available to help you in teaching anatomy. Just go to the new website at anatomy.org to find out more.

Kevin Patton: I have an analogy for pseudogenes that I’ve used for a long time and it is compatible the contemporary ideas about what pseudogenes are or junk DNA, if you want to call it that. The analogy involves my garage. In my garage, I have a pile of scraps of wood that some of which I’ve had it in there for decades. As a matter of fact, some of them go way back. My father was an amateur woodworker and he did a lot of projects. I caught the bug, but I don’t do as much as he did partly because I spent my spare time doing podcasting but when he passed away; I inherited all of that junk wood from his garage. That was one of the first things my mom did as she was clearing things out after my dad died; was to get rid of his junk in the garage and I inherited the wood bits and I keep them for the same reason that he kept them. Yeah. They appear to be trashed, but he and I never threw them away because you just never know when you can reuse them.

Kevin Patton: What these bits of wood consist of are things that were maybe mismeasured, they were cut wrong. They’re still good pieces of wood, they just weren’t usable for that project. They’re defective in some way. They might even have a ding in them or some other imperfection, but some part of it could be salvaged, may be for some other project in the future. Why throw it away? Because wood is expensive; especially certain kinds of wood. If they can be reused, why not have them available so when you’re in the middle of a project you don’t have to stop and then go to a supplier and buy a larger piece of wood than you need when here. You could have a little scrap that could be used and so that’s a lot like what junk DNA is, probably was used at some time in the past. It became defective and yet our genome has hung onto it and maybe it has some current use that we can make of it.

Kevin Patton: For example, those little scraps of wood in my garage. I do use them in real time sometimes to prop up something else or maybe put it under some piece while I’m staining it because I don’t really care whether it gets stain on it because it’s just a junk piece of wood. I might use it underneath something when I’m drilling so that I don’t drill into the work table that I’m using. It does have a function. It sounded very obvious function necessarily to someone looking in from the outside and isn’t that what we are when we’re looking at the genome or outsiders, looking in trying to figure out what’s going on and why is there all that junk? Just like when I opened my garage door, you might look inside and say, “Why does he have all those scraps of wood piled up there?”

Kevin Patton: Actually, they’re organized. They’re not exactly a big unorganized pile, but it might look like at first glance just like pseudogenes, just like junk DNA; looks like Junk. It looks like useless stuff piled up all over the place and yet it might have a use or it might have a use sometime in our evolutionary future. It’s not a perfect analogy, but like any analogy it might trigger some thinking in the student to make the abstract concept of pseudogenes a little more real for them. The reason I’m sharing it with you is, yeah, you can borrow it if you want or more likely it’s going to trigger some idea for some analogy that works better for you and for your students. Take it or leave it or just think of it as junk. I don’t know. Whatever.

Kevin Patton: The free distribution of this podcast is sponsored by the Master of Science in Human Anatomy and Physiology Instruction. The HAPI degree. When’s the last time you had a thorough review of all the core concepts of both anatomy and physiology or comprehensive training in contemporary teaching practice? Check out this online graduate program at nycc.edu/HAPI, that’s HAPI or click the link in the show notes or episode page. There’s always a new cohort forming, so yeah, now’s a good time to check it out.

Kevin Patton: Do you have trouble getting to sleep at night? A lot of people do. I don’t. It kind of well-known among my family and friends to be able to sleep almost any time anywhere. I mentioned in the previous episode, I think it was the previous episode that I’ve led a lot of overseas study tours. Guess what? I found out that some of my frequent travel companions used to take bets on whether I’d be asleep before the plane left the ground. The safe bet was that I would be; but I do know that insomnia is common and can have some dramatic effects on our overall health, including our ability to focus, to think, to teach and learn and just generally function cognitively when we’re awake during the day. About 15 years ago, a study in the Journal, Sleep Medicine showed that white noise can help people sleep by reducing arousals from sudden or jolting ambient noises by filling in the gap between the high and low volume noises that’s in the environment around them and that cap is filled in with a mix of frequencies that are not arousing.

Kevin Patton: This can be as simple as using a fan or can involve so-called white noise machines that offer a choice of different sounds such as, oh, I don’t know; ocean waves or rain or some other soothing sounds that have a mix of frequencies, but you know what else can help sleep? Podcasts. Yeah. That’s right. In fact, there are now some podcasts with the main purpose of helping you sleep. Probably the most well-known is one called Sleep with Me; which has been around for about six years and it’s become wildly popular to help people get to sleep. In case you’re wondering, yes of course, I have a link to this podcast in the show notes and the episode page at the theAPprofessor.org/59. You know what other podcasts can help you sleep? Yeah. You know this podcast, you know that or at least suspected that for some time now because you’ve dozed off while listening to an episode, right?

Kevin Patton: Or maybe you’ve dozed off to two or three or 10 episodes and that’s okay. My purpose in doing this podcast is to help my colleagues and if putting you to sleep is how I can help you, then I’m glad for it. Mostly, well glad for it at least but the thing is almost any podcast can help a person sleep. Some sleep experts have hypothesized that because a podcast is interesting enough to get your mind off of all those recurring thoughts in your head that are keeping you from dozing off peacefully. It can be an effective sleep aid and it helps if the podcast or has a calm voice and is focused on speaking directly to the listener. Well check, check and check. It helps if the podcaster has an empathetic or kind effect because if you get mad while listening, it will prevent you from dozing off because that’s arousing when you get mad.

Kevin Patton: Yeah. Check again and it works best if the content is rather bland or technical or blah, such as droning on and on about pseudogenes or white noise. Okay. Yep. Check again. This podcast checks off all the characteristics that a podcast should have if it’s going to be a good sleep aid. Of course, you have to be ready for sleep. You have to be tired in a relatively comfortable situation. Well, and just generally ready for sleep. That is ready if it were not for all those thoughts that are keeping you just aroused enough to find that falling asleep is difficult. One thing that can ruin a podcast for sleep inducement though is an occasional loud sound. Oops. Oh man, that’s sudden burst of drums and guitar at the end of each segment. That transitions us to the next segment. Hoof that might be what wakes you up. Maybe this isn’t the best podcast for falling asleep after all. Okay. I realize I may have already lost you to sleep right now. Well, that’s okay because-

Kevin Patton: Marketing support for this podcast comes from HAPS, the Human Anatomy and Physiology Society promoting excellence in the teaching of human anatomy and physiology for over 30 years. Hey, if you’re thinking about going to the HAPS annual conference next may in Ottawa, and why wouldn’t you be thinking about that? Don’t forget that you have until February 21st to claim an early bird discount on the registration fee. By the way, February 21st is also the same deadline for workshop and poster proposals, so go visit HAPS at theAPprofessor.org/haps, that’s HAPS.

Kevin Patton: I think I’m going to talk about flashcards again partly because I said I would in the last episode when I explained that I have a lot more to say about flashcards. But also partly because I just really believe in the effectiveness of flashcards for learning A&P and I’ve seen so many A&P students benefit from the use over the nearly four decades that I’ve been teaching. Now, if you haven’t listened to episode 58 yet where we did part one of flashcards or you need some refreshing because it’s been awhile since you listened. I strongly recommend that you hit pause right now and review episode 58 first. I’m going to be referring to some specific comments from episode 58 so it’s probably in your own best interest to get refreshed before continuing on here. Before I continue, I also want to point out why I’m spending so much time talking to you; a teacher about something that students should be hearing.

Kevin Patton: One reason is that as the AP Professors that have been mentored already now, I think one of the center roles of A&P teachers is to help students improve their learning skills. They should already know how to study before they get to me philosophy. When teaching secondary or community college A&P, it doesn’t take any effort at all to see that many students do not know how to learn effectively. But this idea becomes downright dangerous when teaching upper division courses, especially a competitive admission universities or in Graduate courses or in medical or other professional level programs. It’s dangerous because we’re more likely to believe that our students are really good at learning because wow, they got this far, didn’t they? I don’t care which population of students I teach and I’ve taught all those populations I just listed. I know that not everyone is an expert learner. Second, learning specialists are still teasing out what works best for learning, so how are our students or how are we ourselves possibly going to already have all the answers about how to learn?

Kevin Patton: Third, no matter how good we are at something, we can always learn more and develop existing skills to a higher level. Fourth, I’d rather my students leave me with the skills for self-learning all the stuff I didn’t teach them. All this stuff I try to teach them, it just didn’t work. All this stuff yet to be discovered after they leave me, better to learn those skills of self-learning than to be focusing solely on a box of concepts and leave it at that. Another reason I’m talking to you, a teacher right now about flashcards especially all these nifty options and tricks and optional strategies is that, we can have them ready to dispense from our pedagogical pharmacy.

Kevin Patton: When a student comes knocking, asking for help. I mentioned in the previous episode, episode 58; that a former professor used a chat with me and my study buddy to diagnostically probe what had gone wrong leading up to our dismal failure in any college class. Remember that test that blew up and sank to the bottom? That diagnostic probing and subsequent recommendation by our professor to use flashcards as a pedagogical treatment plan is something I took to heart back then as a student, but I also started using that approach when I began teaching. Yeah. Flashcards are probably good for 99% of learners.

Kevin Patton: We professors can safely prescribe flashcards for any student without knowing anything about that student or their learning strategies or habits, or if they even have any learning strategies or habits. We’ll know that learning will improve if they use flashcards. It’s like when a physician prescribes exercise, exercise helps almost every malady, right? It prevents a whole bunch of problems, too. I still want my physician to ask me probing questions, maybe do a test or two if necessary and thoughtfully consider my diagnosis and suggest a treatment plan that will help me. That may include exercise, hey, it’s probably going to exercise, but even so I know that it’ll be specific to all of my needs at the time.

Kevin Patton: When I’m recommending is that we take that approach when dealing with students. The therapy model, where we work with individuals and try to figure out what’s not working and then formulate a plan to get it working and like exercise being recommended in medical therapy. Flashcards are likely to be part of what we recommend to our students. Here’s where all those bells and whistles come in. If we, as teachers know a lot of different options and approaches to using flashcards; our prescription of a treatment plan will be a lot more effective. That’s because we can give specific suggestions to try based on that student’s particular case. So in a way, this discussion about the details and options of using flashcards is helping us become better learning therapists when our students seek out our advice.

Kevin Patton: Something else I want to build on from episode 58 where we started the discussion of flashcards is that it’s best to remember that flash is the goal. It’s not the learning mode. Recall from that previous discussion that researchers have found that flashcards are often used too fast by students, which makes them less effective for learning; but that’s in the learning phase. We want to work through that learning phase over days or maybe even weeks and finally get to what, why don’t we could call it the flash point? The point at which we can flash or fly through each one quickly because we’ve already accomplished our learning goals.

Kevin Patton: I also want to mention that in the preview to this episode that is preview episode number 59. We clarified the use of the terms obverse and reverse relative to flashcards, so you might want to go back and catch that if you happen to doze off during the preview of this episode, episode number 59. Yet another idea already mentioned in episode 58 but that I want to emphasize again is that students should start making flash cards from the very start of a new topic in class. They ought not to wait until they are done learning a topic and are cramming for a test, but we know that that’s how many students use flashcards. For them, studying is something you do right before a test. It’s not the underlying practice of learning that forms the foundation of each and every day of the semester that it must be if they’re going to be successful.

Kevin Patton: We need to do what we can to get them on the right track regarding ongoing learning practice that starts from the get go. I also recommend the practice of doing flashcard reviews regularly and in short bursts. The first thing I learned as a wild animal trainer, something you may recall I did very early in life is that training new behaviors and practicing old behaviors just won’t work unless it’s done in very short sessions. I have found that there’s a time limit on the cognitive load of learning that if exceeded can do more harm to learning than good. Like many things about teaching that I first learned as a lion tamer; a few short sessions every day can do a lot of good without all that much effort. Not only that, but it can actually be a fun challenge when learning is practiced this way, that is in short sessions.

Kevin Patton: As we wind up the second full year of the A&P Professor podcast, it’s a good time for reflection. Remember in episode 17, I advocated that we all do debriefings or reflections at the end of each academic year; so it’s not surprising I’m doing that now with this podcast. Part of that process for me this year is gathering feedback from you, so I’m asking you for about five minutes of your time to fill out a survey. It’s put together by a team of specialists to help me tweak and improve things. No matter if you’re a new listener or a long time listener. Whether you’ve listened to just one episode or just part of an episode or listened to all the episodes, I’d really appreciate your time to respond to this anonymous survey. Just go to theAPprofessor.org/survey.

Kevin Patton: Let’s get to some specific flashcard tips, tricks and strategies. First, an important idea about flashcards that underlies all these strategies; that is the idea that terms represent concepts. Terms aren’t just words, they have meaning, and that meaning is the concept that each word or phrase represents. I think that when we recognize this, we can easily see past the mistaken notion that learning terms and by extension learning with flashcards is somehow rote memorization without meaning. Well. Okay. I guess it can be rote memorization without meaning. I guess when I’m trying to get at is it doesn’t have to be as long as we do some metacognition. That is as long as we do some thinking about our thing and take note of the deep meaning behind the representation of ideas on our flashcards.

Kevin Patton: One common strategy that I haven’t really gone into much is the use of pictures on flashcards. Some concepts lend themselves more to this than others. One that pops into mind right now is histology. I want my students to be able to recognize some of the key types of tissue, visually. This comes early in the A&P one course and it often hits students’ right in the face. It’s hard getting the skills needed to recognize countless different examples of the same tissue type. They all look like abstract art anyway, don’t they? Yeah. It’s like a Jackson Pollock painting with all these paint drips off a place, at least when you’re first starting. It doesn’t seem to make any sense at first. I’ve been there, done that as a student myself. But as you know from your own learning of histology, the more you practice recognizing tissues, the easier it gets until you can do it in your sleep. Like during those occasional histology nightmares. What?

Kevin Patton: I can’t be the only one to get the odd histology nightmare, now and again. Getting back to the point, recognizing tissues, bones, bone markings, muscles, nerves, vessels, just about any anatomical structure is something that pretty much requires a visual approach. Now, one way to produce these visual flashcards if a student is making them rather than purchasing or downloading them, is to draw the visual elements. Drawing is a great way to learn while making the cards and it’s likely to have more meaning as the drawings are used in daily review.

Kevin Patton: Another method is to print out images found on the internet or scanned from the textbook or Lab Atlas. Then the image can be taped or pasted onto one side of a flashcard. The obverse could have the name of the structure and the reverse could have the picture or the picture could be on the obverse and then the name of the structure could be on the reverse. As a matter of fact, the same card can be used both way obviously, but it’s how you approach the card which one’s going to be the obverse or front side and which is going to be the reverse or backside. Considering how ubiquitous, mobile devices with built in cameras have become. I’ve seen a lot of students taking photos of lab models to section specimens, microscope views, teaching charts, and even my diagrams on the whiteboard and then making flash cards with them.

Kevin Patton: What about mnemonics? As you know, a mnemonic device is anything that helps you remember something. In a way, flashcards by their very nature are themselves mnemonic devices. Usually when we think of mnemonics, we think of simple phrases or sentences where each word starting letter is the same starting letter of a member of a list of things we’re trying to remember like the order of the 12 classic cranial nerves. Students could incorporate mnemonic phrases into their flashcards. For example, they could put the term or concept on the obverse and then put the mnemonic device with its meaning that is the actual list they’re trying to learn on the reverse of the card.

Kevin Patton: Or they could put them in a mnemonic sentence with no clarifications on the obverse and the actual list to be learned on the reverse. Now I’m going to circle back to another strategy in just a minute or two, but before I do; let’s talk about color coding. For those of us with so-called normal color vision, color can be a powerful visual tool in helping us to learn. Besides simple memorization, using color coding can help us learn to categorize ideas and see relationships; thus moving us into higher level thinking and deeper understanding. There are a lot of different ways to use color coding with flashcards enough different ways that not only could that topic be its own episode, it could be its own podcast series. So clearly, I’m only going to be able to scratch the surface. I don’t know. Wait. How about if I draw the rough outline and you color in the details yourself?

Kevin Patton: Okay. Stop groaning. That’s not a pun, it’s a metaphor. One general way to apply color coding of flashcards is to use different color cards. As you know, these are easily available to students. I’m still waiting to see index cards available and my favorite color though, my favorite color is plaid. I can’t be the only one. Right. You’d think somebody would have come up with plan index cards by now. Another way to use color coding is to use different colors of pen or pencil within a single card. Now all mine are green because I always carry a green pen with me. As a matter of fact, sitting right next to my microphone are, let’s see; one, two, three, four green pens. I talked about green pens back in episode six if you want to hear why I use them. One does have the option of using a variety of colors of pen or even highlighter when color-coding information within a flashcard and when could use colored index cards and colored pens or pencils and/or highlighters.

Kevin Patton: You can have all kinds of colors going on. Now for you using plain index cards, I may not worry. That may be too many colors. Of course. All this begs the question, what exactly are we coding here? How are we applying color coding? Well, there’s all kinds of possibilities. We could color code cards by topic which might help in keeping them all organized in a big box like we talked about last time. A student could use different colors for text based cards and those that primarily use an image. You have text cards, all one color and image cards on another color. Or you could have all the histology flash cards be one color. You’re going to have histology flashcards mixed in with almost any topic in A&P, right? If they’re all one color, then you can pull out those histology flash cards right away.

Kevin Patton: Or anatomy cards could be a different color than physiology cards. Or we can use color coding for different levels of importance or complexity. There’s really an unlimited variety of different kinds of categorization to which we can apply color coding. It’s whatever an individual student finds to be most helpful in their own efforts to construct their own conceptual framework of A&P, which brings us to another option for using flashcards that is adding layers of information. In episode 58, I talked about keeping flashcards simple at first but then adding more layers of information as learning continues as that module in the semester unfolds or is that semester unfolds or as the next semester unfolds. I like to use a constructivist model of learning where I think of students learning A&P or learning anything really as if they’re constructing a framework of knowledge which we can call a conceptual framework.

Kevin Patton: When we plan out our story of human structure and function that is when we design our course. We usually start out with some simple foundational ideas like what chemicals are and how they work. We explain the basic ideas of acid and bases and then survey some major groups of biochemical and all kinds of core topics within chemistry and then we come back to that later and add a layer of knowledge and understanding. When we talk about what those bio molecules are doing in the cell and add yet another layer when we get to the tissues and then to each organ of each system. So for two semesters we’re adding layer by layer. In other words, we don’t explore the concept of protein. For example, all at once a student’s understanding of the concept of protein evolves and grows each time it’s encountered in a new context.

Kevin Patton: In a new chapter of the story we’ve planned out in our course, we can call this layering or we can call it interleaving or we can call it a spiraling curriculum or we can call it constructing a conceptual framework. It goes by a lot of names, but it’s a real basic idea of learning. Doesn’t really matter what we call it, I guess as long as we’re doing it. My point here is that students can add layers of content to their flashcards to reflect this manner of learning. This practice becomes a concrete reflection of the learning process going on inside a student’s mind. It also promotes a student going back to review what they know and understand about the concept already, thus reinforcing prior learning. Beyond that, I think this practice of adding layers of content to flashcards also promotes thinking about connections between concepts, thus forming those interconnecting crossbeams that strengthen a student’s conceptual framework as its being built up.

Kevin Patton: Here’s a spot where we could add color coding within a card. The first entry on the reversible flashcard could be a simple definition that could be kept near the top edge of the card and be highlighted in yellow. Then as more information is added below, either not highlighted or highlighted in a different color or written with a different color pen or pencil, it would stand out. That core information would be easily identifiable at the top in its own color and the added layers of information would be slightly separated but all there on the same card. A lot of my students add other kinds of information to their flashcard, for example; references to chapter number, to page number, to figure number, table number in their textbook or in their lab manual or both. I’ve even seen students move out of A&P into nursing or some other program and pull out their A&P flashcards and start adding cross-references to their nursing theory textbooks or their clinical care references.

Kevin Patton: Some students use cross-references to other cards in their growing collection. Besides adding layers of information, I’ve seen students add physical layers to their flashcards. For example, when using mnemonic sentences. On the obverse or they’ll identify some sort of list like the cranial nerves. Then on the reverse, they’ll have the mnemonic. Then they either confirm that they got the answer correctly before flipping over the flash card, or they’ll now try to derive the actual nerve names using the mnemonic that’s on the reverse. To check themselves at that point, they’ll flip up a little flap that they’ve made on the reverse by taping a partial card to the bottom half of the reverse side. Under that flap is where they’ll have the actual list of nerves, so that makes it a two-tiered flash card. So that’s what I mean by adding physical layers to the flash card that allows us more room and more ways to use the added layers of information. It makes it like a two-step flash card.

Kevin Patton: Yep. I did it again. I went on and on about flashcards and once again there’s more to town. That’s okay though because there’s another episode coming in a couple weeks. I can pick up the story then. Right. Of course, the problem with that scenario is that between now and then, how I’ve thought even more to say about flashcards. Let’s making it necessary to go on for yet another episode after the next one. I’ll try to be careful though. I guess anything extra I have on flash cards after the next episode can wait in my file for a while along with all those other ideas that they’re waiting to be used on some new episode further along in the future. Oh, wait, wait, wait, wait.

Kevin Patton: In the last episode, I promised some amazing feats with flashcards; like levitating flashcards and I don’t want to leave you disappointed. If you go to the tap app on your device, which you can install by going to your devices app store and searching for the A&P Professor or just clicking the link in the show notes or the episode page at theAPprofessor.org/59. And you’ll see there’s a bonus video there that shows you exactly how to get a flashcard to levitate. Really, you can check it out. If you hang on in the video, pass the blackout at the end. That’s where I reveal the secret. Don’t turn it off too quick or you won’t know how to do it yourself.

Kevin Patton: Don’t forget that I always put links in the show notes and at the episode page at theAPprofessor.org, in case you want to further explore any ideas mentioned in this podcast or if you want to visit our sponsors. You’re always encouraged to call in with your questions, comments and ideas at the podcast hotline, 1-833-LION-DEN, that’s 1-833-546-6336 or send a recording or written message to podcast at theAPprofessor.org. I’ll see you down the road.

Aileen: The A&P Professor is hosted by Dr Kevin Patton, an award-winning professor and textbook author in human anatomy and physiology.

Kevin Patton: Putting this podcast in the microwave is not recommended. Support for this episode comes from the American Association of Anatomists, the Human Anatomy and Physiology Society and the Master of Science in Human Anatomy and Physiology Instruction.

Dr. ZZzzz: Hey there friend, the podcast episodes over. Now it’s time to turn the volume down a bit and settle in for the Delta Wave Radio Hour. I’m your host, Dr. ZZzzz. Don’t forget my dear friend that we do not listen while driving or operating machinery. Before I play you a dreamlike track by REM, I have something special here dedicated to listeners Dic and Ellen, who tune in from all the way up there in Calgary. Here it is with a smooth Atlanta sound from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. It’s called Influenza.

Dr. ZZzzz: What is influenza or the flu? Well, flu is a contagious respiratory illness caused by influenza virus that infects the nose, throat, and sometimes the lungs. Influenza or flu can cause mild to severe illness and at times can lead to death. Flu is different from a cold. Flu usually comes on suddenly.

Dr. ZZzzz: People who have flu often feel some or all of these symptoms, either or feeling feverish or chills. It’s important to note that not everyone with flu will have a fever or a cough, sore throat, runny or stuffy nose, possibly body aches, headaches, fatigue or tiredness. Some people may have vomiting and diarrhea, although this is more common in children than adults. Most experts believe that flu virus is spread mainly by tiny droplets made when people with a flu cough, sneeze or talk. These droplets can land in the mouths or noses of people who are nearby. Less often, a person might get flu by touching a surface or an object that has virus on it and then touching her own mouth. Those are possibly their eye.

Dr. ZZzzz: A 2018 CDC study published in Clinical Infectious Disease looked at the percentage of the US population who were sickened by flu using two different methods and compare the findings. Both methods had similar findings which suggested that on average, about 8% of the US population gets sick from flu each season with a range of between 3% and 11% depending on the season. The same CID study found that children are most likely to get sick from flu and that people 65 and older are at least likely to get sick from influenza. Median incidents of Ohio where attack rate by age group were 9.3% for children zero to 17 years, 8.8% for adults, 18 to 64 years, and 3.9% for adults 65 years and older. This means that children younger than 18 are more than twice as likely to develop a symptomatic flu infection as adults 65 and over.

Dr. ZZzzz: You may be able to spread flu to someone else before you know you’re sick as well as while you were sick. People with flu are most contagious in the first three or four days after their illness begins. Some otherwise healthy adults may be able to infect others beginning one day before symptoms develop and up to five to seven days after becoming sick. Some people, especially young children and people with weakened immune systems might be able to infect others for an even longer time. The time from when a person’s exposed and infected with flu to when symptoms began is about two days, but it can range from about one to four days. Complications of the flu can include bacterial pneumonia, ear infections, sinus infections, and worsening of chronic medical conditions such as congestive heart failure, asthma, or diabetes. Anyone can get flu, even healthy people and serious problems related to flu can happen at any age, but some people are at high risk of developing serious flu related complications if they get sick.

Dr. ZZzzz: This includes people 65 years and older; people of any age with certain chronic medical conditions, pregnant women and children younger than five years. The first and most important step in preventing flu is to get a flu vaccine each year. Flu vaccine has been shown to reduce flu-related illnesses and the risk of serious flu complications that can result in hospitalization or even death. CDC also recommends everyday preventive actions like staying away from people who are sick, covering cough and sneezes and frequent hand washing to help slow the spread of germs that cause respiratory that is nose, throat, and lung Illnesses like flu. It’s very difficult to distinguish flu from other viral or bacterial respiratory illnesses based on symptoms alone. There are tests available to diagnose flu. There’s more information available from CDC.gov. Sshh.

This podcast is sponsored by the

Human Anatomy & Physiology Society

This podcast is sponsored by the

Master of Science in

Human Anatomy & Physiology Instruction

Transcripts & captions supported by

The American Association for Anatomy.

Stay Connected

The easiest way to keep up with new episodes is with the free mobile app:

Or wherever you listen to audio!

Click here to be notified by email when new episodes become available (make sure The A&P Professor option is checked).

Call in

Record your question or share an idea and I may use it in a future podcast!

Toll-free: 1·833·LION·DEN (1·833·546·6336)

Email: podcast@theAPprofessor.org

Share

Tools & Resources

TAPP Science & Education Updates (free)

TextExpander (paste snippets)

Krisp Free Noise-Cancelling App

Snagit & Camtasia (media tools)

Rev.com ($10 off transcriptions, captions)

The A&P Professor Logo Items

(Compensation may be received)