Zoom Fatigue & Other Symptoms of Pandemic Teaching

TAPP Radio Episode 73

Episode

Episode | Quick Take

What causes Zoom fatigue and how can we prevent it? Host Kevin Patton tackles that as well as another nasty effect of pandemic teaching: stress cardiomyopathy. Plus updates in sensory physiology, the value of keeping skill lists, and the Book Club recommends Chris Jarmey’s Concise Book of Muscles.

- 00:40 | Updating Our Skill Lists

- 01:59 | Updates in Sensory Physiology

- 07:30 | Sponsored by AAA

- 08:05 | Book Club: The Concise Book of Muscles

- 12:05 | Sponsored by HAPI

- 14:26 | Zoom Fatigue

- 29:11 | Sponsored by HAPS

- 30:06 | Pandemic Heart: Stress Cardiomyopathy

- 39:48 | Staying Connected

Episode | Listen Now

Episode | Show Notes

The heart was made to be broken. (Oscar Wilde)

Updating Our Skill Lists

1.5 minutes

Anatomy professor Amanda Meyer reminded us on Twitter that pandemic teaching has given us a lot of new skills that we should be adding to our skill list in our curriculum vitae (CV).

- How to describe skills in your CV (some hints) my-ap.us/308zLMR

Updates in Sensory Physiology

5.5 minutes

A few content updates to spice up our teaching.

- Is “water” a primary taste in mammals?

- Scientists discover a sixth sense on the tongue—for water (summary of research) my-ap.us/2Zn5uuI

- The cellular mechanism for water detection in the mammalian taste system (research paper) my-ap.us/3etufcO

- Do we need cold receptors to feel warmth?

- Changing how we think about warm perception (summary of research) my-ap.us/2DAV8Pj

- The Sensory Coding of Warm Perception (research article) my-ap.us/2DyHNqF

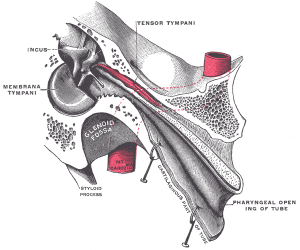

- Can you hear your tensor tympani?

- Some People Can Make a Roaring Sound in Their Ears Just by Tensing a Muscle (brief news article) my-ap.us/38Ur7pu

- Voluntary contraction of the tensor tympani muscle and its audiometric effects (case study) my-ap.us/2CAGxmk

Sponsored by AAA

1 minute

A searchable transcript for this episode, as well as the captioned audiogram of this episode, are sponsored by the American Association for Anatomy (AAA) at anatomy.org.

Don’t forget—HAPS members get a deep discount on AAA membership!

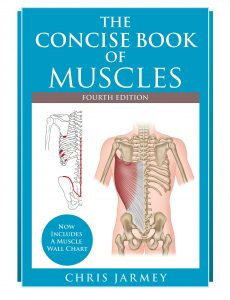

Book Club

4 minutes

- The Concise Book of Muscles

- by Chris Jarmey

- amzn.to/3h1GW07

- For the complete list (and more) go to theAPprofessor.org/BookClub

- Special opportunity

- Contribute YOUR book recommendation for A&P teachers!

- Be sure include your reasons for recommending it

- Any contribution used will receive a $25 gift certificate

- The best contribution is one that you have recorded in your own voice (or in a voicemail at 1-833-LION-DEN)

- Contribute YOUR book recommendation for A&P teachers!

- For the complete list (and more) go to theAPprofessor.org/BookClub

Sponsored by HAPI Online Graduate Program

2.5 minutes

The Master of Science in Human Anatomy & Physiology Instruction—the MS-HAPI—is a graduate program for A&P teachers, especially for those who already have a graduate/professional degree. A combination of science courses (enough to qualify you to teach at the college level) and courses in contemporary instructional practice, this program helps you be your best in both on-campus and remote teaching. Kevin Patton is a faculty member in this program. Check it out!

Zoom Fatigue

15 minutes

Zoom meetings, webinars, classes, etc., make me tired just thinking about them. I think this is part of Zoom fatigue, that exhaustion we feel from participating in video meetings. Here’s a discussion of what Zoom fatigue is and how to combat it. I’m thinking of hosting a virtual telethon to support finding a cure. You in?

- How to Combat Zoom Fatigue (article talked about in this segment) my-ap.us/3fx0V6O

- Zoom fatigue is real — here’s why video calls are so draining (brief article) my-ap.us/3fs8USo

- ‘Zoom fatigue,’ explained by researchers (brief article) my-ap.us/2AZfv83

- ‘ZOOM FATIGUE’ IS REAL. HERE’S WHY YOU’RE FEELING IT, AND WHAT YOU CAN DO ABOUT IT. (brief article) my-ap.us/38XnCyq

Sponsored by HAPS

1 minute

The Human Anatomy & Physiology Society (HAPS) is a sponsor of this podcast. You can help appreciate their support by clicking the link below and checking out the many resources and benefits found there. Watch for virtual town hall meetings and upcoming regional meetings!

Pandemic Heart

10 minutes

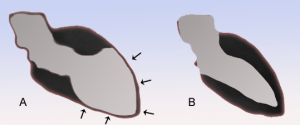

I’m calling it pandemic heart but experts call it stress cardiomyopathy. It’s also called broken heart syndrome and several other names. One of which involves fishing for octopuses. Whatever you call it, it’s incidence has more than doubled due to the pandemic.

- Word Dissection

- stress cardiomyopathy

- takotsubo cardiomyopathy

- apical ballooning syndrome

- Clarification: The ballooning characteristic of stress cardiomyopathy is often more pronounced in the apical region of the left ventricle.

- Incidence of Stress Cardiomyopathy During the Coronavirus Disease 2019 Pandemic (research article) my-ap.us/3emx0g1

- Researchers find rise in broken heart syndrome during COVID-19 pandemic (news summary of the research) my-ap.us/2ZmkKb7

- Stress Cardiomyopathy Symptoms and Diagnosis (disease summary from Johns Hopkins) my-ap.us/2CtjE4x

- Takotsubo Cardiomyopathy (disease summary that include a lot of great still and video images of this condition) my-ap.us/3ekWL09

- Ancient catching octopus trap. (video showing one method for using takotsubo to catch octopuses) youtu.be/ac9XSKjabjI

- Diagram of stress cardiomyopathy (A) compared to a normal ventricle (B) by J. Heuser my-ap.us/303stda

Need help accessing resources locked behind a paywall?

Check out this advice from Episode 32 to get what you need!

Episode | Captioned Audiogram

Episode | Transcript

The A&P Professor podcast (TAPP radio) episodes are made for listening, not reading. This transcript is provided for your convenience, but hey, it’s just not possible to capture the emphasis and dramatic delivery of the audio version. Or the cool theme music. Or laughs and snorts. And because it’s generated by a combo of machine and human transcription, it may not be exactly right. So I strongly recommend listening by clicking the audio player provided.

This searchable transcript is supported by the

This searchable transcript is supported by the

American Association for Anatomy.

I'm a member—maybe you should be one, too!

Introduction

Kevin Patton:

Oscar Wilde once wrote, “The heart was made to be broken.”

Aileen:

Welcome to The A&P Professor. A few minutes to focus on teaching human anatomy and physiology with a veteran educator and teaching mentor, your host, Kevin Patton.

Kevin Patton:

In this episode, I talk about keeping skill lists, Zoom fatigue, pandemic heart, sensory updates, and a new book club recommendation.

Updating Our Skill Lists

Kevin Patton:

One of the things that I often suggest to the A&P faculty that I mentor is to keep a list of all the skills they acquire as they acquire them and then add them to their CV or curriculum vitae, or vitae as some folks call it. Recently on Twitter, Amanda Meyer, who is an anatomy faculty down in Perth, Australia, tweeted that we all need to remember to add all the new things we’re learning as a result of doing pandemic teaching. All those wild and wacky and wonderful new technical skills we’ve mastered. All that new software we’ve wrestled with, the different teaching strategies we’ve experimented with.

Kevin Patton:

Oh yeah, and those new ways of communicating with students and methods for helping them communicate with each other. Wow. All kinds of things we’ve learned recently, huh? So let’s make a list and then we can add that to our CV and we’ll have a lot to report during our next faculty evaluation or promotion process too. Amanda, thanks for the reminder.

Updates in Sensory Physiology

Kevin Patton:

I know, it’s been a while since I’ve shared a content update, but well, with all the focus on pandemic teaching, I felt like it was best to focus on that for a while if I want to be helpful to the A&P teaching community. And I still think that kind of thing is helpful. But that’s what I’ve been hearing from you. But I think a brief pause to focus on some interesting science updates is appropriate too.

Kevin Patton:

So in this episode, I have a few updates on sensory physiology. The first one is about our sense of taste and whether we can taste water as a separate primary kind of taste or not, like sour, salty, sweet, and bitter. Not long ago, some researchers tried to figure that out. And by doing a series of different experiments showed that mice seem to get a major part of their sensation of water from the same taste receptor cells that they use for sour tastes. That is for pH, for acids. If they knocked out those receptors, the mice had trouble distinguishing water from other tasteless liquids. And if they manipulated the cells to be triggered by blue light, mice started to drink the light.

Kevin Patton:

I want to see a video of that. I couldn’t find a video of that when I looked around, maybe it’s there and I just didn’t see it. They just kept on drinking the blue light because they clearly weren’t getting any of the water that they really wanted. It still doesn’t answer all our questions about water as a taste, but it’s a step. Probably sensing water will likely involve other senses like smell, temperature, pressure, and so on and possibly involve various mechanisms working together to eventually produce the perception of water in our brain. But like I said, it’s a step. Another bit of sensory news comes from the world of temperature sensing. I have always thought about sensing temperatures with our skin as a matter of warmth receptors detecting warmer temperatures and cold receptors detecting cooler temperatures.

Kevin Patton:

And that’s been the prevailing view for a while, but new research in mice shows that it may be a little bit more of a team effort. That is, when we grab that cup of tea, Earl Grey hot with our hand, it’s not just the triggering of heat sensitive receptors. A critical part of the sensing also comes from inactivation of the cold sensitive receptors. It seems that without that inactivation of cold receptors by the warmth of the tea cup, it would either take longer to feel the warmth or well, may not even be able to feel that warmth at all. Now there’s a lot more to work out for sure, but this idea is kind of cool. So cool, it’s hot. Now my third eye… sorry about that.

Kevin Patton:

My third item relates to hearing. First remember that there’s a tiny skeletal muscle in the middle ear called the tensor tympani. It originates in the wall of the auditory tube and inserts on the malleus bone, which in turn is connected to the eardrum or tympanum. The role of this muscle seems to be to reduce loud sounds by dampening the vibrations of the tympanum as the muscle contracts. This is especially important in chewing, but it can be helpful with other loud and potentially damaging sounds. You may already know that muscles make a rumbling noise when they’re tensed. If you tense any large muscle or group of muscles, let’s say your upper arm muscles, and then press them against your ear in a quiet environment, you might be able to hear that rumbling.

Kevin Patton:

Well, the tensor tympani being right there in your ear can be heard by some people when it’s tensed. If you can contract it voluntarily, you can produce a rumbling sound. Or if you experience a yawn, you may be able to hear that rumbling when you’re yawning very deeply. Now I think that whole idea is pretty fun and amazing, but it’s not really a new discovery. It was published way back in the 1880s. But if you missed it then, you may have seen some of the more recent articles that talk about it like those that I have linked in the show notes and episode page. One of them is a case study of a young man who thought he had a hearing condition, but it turned out that he was voluntarily contracting both tensors tympani and he thought he had some kind of weird form of tinnitus or tinnitus. That could be a fun case study item for my A&P students.

Sponsored by AAA

Kevin Patton:

A searchable transcript and a caption audiogram of this episode are funded by AAA, the American Association for Anatomy. You can find them at anatomy.org. You may want to go to their webinar page under the resources tab to find out what amazing experience awaits you. They’re always organizing or sponsoring really helpful virtual presentations and other resources that are particularly helpful during this era of pandemic teaching.

Book Club: The Concise Book of Muscles

Kevin Patton:

Hey, let’s step into the bookshop and see what we may want to add to our personal and professional bookshelf. Oh, look here. It’s a book about muscles called, The Concise Book of Muscles, which is a great name for a book about muscles I guess. I like muscles and I like concise presentations of anatomy and physiology, so far so good. It’s written by Chris Jarmey, who was considered an outstanding teacher by his students and an all around nice guy. So yeah, definitely a book worth opening. When I do open it, I’m immediately drawn in by the outstanding art, not just pretty and it is, but really, really clear. When I’m looking at information about a particular muscle, and I want to see where it is and where exactly the origin and insertion are, I want all that to be clear to me right away.

Kevin Patton:

One of the several things I love about this book is that it shows a great illustration of each muscle isolated enough that I can see the whole thing to anatomical context. I can’t always do that in a typical A&P textbook or even any of those huge, awesome anatomical atlases. There just isn’t the space to really have all the muscles in large clear illustrations. So yeah, I’ve got a lot of other references for muscles, but this one is a great supplement to add to the information I already have on my bookshelf. There’re also supporting illustrations showing where the various origins and insertions are on the skeleton relative to each other. And get this, summary tables. I love, love, love, summary tables like these. They make accessing detailed information about each muscle easy to find and easy to digest.

Kevin Patton:

Besides that, by putting information about muscles from one region side by side, I can see patterns and draw insights on my own. I can’t easily do any of that when all I have is paragraphs of narrative text, and as the name implies, it’s, well, concise. That is, it just has that information that I’m typically looking for, leaving out details that usually get in the way when I’m reading a book to find the core characteristics of a particular muscle. I can see myself using this book, not only for my own exploration and reference, but also as a teaching tool. I want a copy in my office and in the teaching lab so that I can pull it out anytime and show a student exactly what’s going on with that muscle they’re having trouble learning.

Kevin Patton:

Something a bit different than the jumble of muscles they might see in their textbook, lab manual, lab model, or dissection specimen. Hey, I was thinking of getting a cup of tea from the corner of the bookshop over there and finding a comfy chair to sit and spend more time with this book. But you know what, I think I’ll take it home and add a couple of cats and a dog to that scenario and spend even more time with it, then put it on my shelf in a handy spot. I might need two copies so I can have it handy wherever I need it when I need it. Remember, it’s The Concise Book of Muscles by Chris Jarmey. You can get it by clicking the link in the show notes or episode page, or simply ask your college librarian to order you a copy.

Sponsored by HAPI

Kevin Patton:

Regular listeners to this podcast know we’re sponsored by the Master of Science in Human Anatomy and Physiology Instruction. They’re a HAPI degree. I’m on the faculty of this program and I recently got a call on the podcast hotline from one of our happy students.

HAPI Student:

Hi, Dr. Patton. I am a current student in the HAPI program at the New York Chiropractic College and currently a part-time anatomy instructor at Community College. And I wanted to take a moment to share some exciting news. I am about halfway through the HAPI program. And during this trimester, I had an opportunity to apply and transition into a full-time teaching position at my local community college. My faculty mentor had highly encouraged me to sign up for the HAPI program to strengthen my human anatomy credentials, and it paid off. The HAPI program helped me every step of the way to prepare for the interview and the teaching demonstration process. I have never applied for a position like this before, and I feel that the HAPI program was vital to my success and securing the position.

HAPI Student:

Because of the style, delivery, and content of the HAPI program, I felt at ease during my interview and communicating about my teaching abilities, pedagogical philosophies, and my content delivery style. A big topic in my interview was transitioning brick and mortar classes to an online delivery format. I was able to enthusiastically talk about how I was prepared to do this and how I’m currently training in the HAPI program by learning even more about online delivery options and methods. Even though I’m going into my eighth year of teaching, I am amazed at how much this program has improved my knowledge and teaching practice. I am very thankful for the direct impact the HAPI program has had on me so far.

Kevin Patton:

You know what, you can join us to charge up your teaching skills and content mastery in the HAPI program. Just go to nycc.edu/hapi, that’s H-A-P-I, or click the link in the show notes or episode page.

Zoom Fatigue

Kevin Patton:

In late April of this year, the Harvard Business Review published an article in which authors, Liz Fosslien and Mollie West Duffy coined the term Zoom fatigue. And many of us, me included, saw that and sighed to ourselves and said, “Yeah, I’ve got that.” Since then, I think my Zoom fatigue has gotten worse. So as part of my therapy, I’m going to talk about it a little bit, kind of get it out of my system a little bit. That’s therapeutic, right? First of all, what is Zoom fatigue? And more importantly, does my insurance cover it? What’s the code for that disorder? Well, I’m confident there’s no code for it. And I’ll bet your insurance won’t cover it specifically, but maybe some of its side effects or symptoms are covered. I bet they are.

Kevin Patton:

According to most of the articles I’ve read, none of which are based on research specifically on Zoom fatigue, Zoom fatigue is that drained feeling you get from doing video calls and webinars, and web meetings, and even video parties. Now, since this is still a hypothetical syndrome, I’ll throw in my suggestion that another symptom is that dread I sometimes feel as I anticipate a web meeting or a webinar. Most web meetings I’m part of, I’m really looking forward to in many ways, but there’s often that slight feeling of dread mixed in there that it’s going to be yet another one of those things that just, well, wears me out. What is it that wears us out about those meetings and how can we maybe manage it? I think for me, part of it is that I’m an introvert.

Kevin Patton:

That doesn’t mean I don’t like interacting with people, even large groups of people, not at all, but it does mean that it wears me out and I need a bit of downtime to recharge. So I don’t think we can rule that out as a contributing factor to Zoom fatigue. Another factor cited by some is that we often have to put more energy and concentration in the conversations during a Zoom meeting. We’re staring at the screen for a while, sometimes trying to follow audio that’s tinny or quiet, or has a lot of distracting hums or other noises. And that takes more mental energy than we might realize. Multitasking is something else thought to contribute to Zoom fatigue. A lot of us do other stuff while we’re on Zoom meetings, right? Check emails, work on our notes for that course, check the discussion board for that other course, maybe play some solitaire, whatever.

Kevin Patton:

Another thing is that Zoom meetings almost require multitasking. Even if you’re not shifting at least part of your focus to some other outside task, you’re probably trying to follow the chat or even carry on a conversation and chat while still trying to be part of the video meeting. I can’t tell you how many times I’ve been called out on that. All of a sudden, I hear my name being mentioned and I find myself having volunteered for something because I was caught off guard because I was watching the chat and not really listening very closely to what was going on in the video part. Now, I haven’t had any disasters in that regard, but I feel one must be coming if I don’t get any better at that.

Kevin Patton:

And of course, we’re checking out who else is in the meeting by going down the roster of participants and perhaps trying to check out what books people have on the shelf behind them, or try to figure out what breed of dog is that sleeping on the floor. Or maybe whether that’s a cat or a pillow that’s on that chair. Yikes. No wonder our brain feels taxed trying to do all that at once. And if you’re one of the presenters or the only presenter, or maybe the presider of a Zoom meeting, there’s even more pressure on your brain because you have to attend to all of that except maybe the dog and the cat part. And you probably have more pressure because you have to watch for your turn and make sure all your resources are still there where you put them and are ready to go when it is your turn.

Kevin Patton:

So what I often do is just decide, I’m not going to do anything extra, Zoom meetings are hard enough. I’ll check my email later, do all that stuff some other time. I don’t do it when I’m teaching a face to face class, so I can avoid doing it in a Zoom meeting or a webinar. I just close all those windows and tabs so I’m not tempted. And I often just scan the chat looking for somebody that’s maybe tagging me on something. And I just kind of skim over the rest very lightly because if I stop and read every word, I’ve now just tuned out the main video part of the meeting. I’ll find myself getting volunteered for something again.

Kevin Patton:

I just followed a Twitter conversation recently where folks were piling on, they were piling on presenters who turn off chat during their presentations because they said webinars should be interactive. And what kind of ego that presenter must have to turn off chat. They said that what’s said in chat is way more important than what any expert has to say. Yeah, those are strong opinions at bay. But as a presenter who can barely talk as I advance slides, I just can’t keep focused on the story I’m telling while I’m presenting if I’m having to look at chat too and react to things going on in chat. Now maybe before and after I’m presenting my story, but not during. Wait, I have to answer this question on chat. Hold on a minute. Okay. Yeah. Okay. Okay. I’m back.

Kevin Patton:

Now where was I? I don’t know. Where was I? Oh yeah, yeah. Something about Zoom fatigue. I lost my place in my notes. I’m going to have to pick up with the next thing I see. Oh, wait, wait, wait. I just remembered. Can’t we pick up the conversation later on after the webinar in email or Slack, or at Listserv, or web community after the webinar is over? Do I have to do it while the presenter is presenting? Do we allow our students to chat on their device while in a face to face class? Do we like it when our dean is chatting on their device while we’re bringing up an important concern during a faculty meeting? Yeah. I didn’t think so. Sure. There are times and places for such interactions, but I think sometimes it’s neither the time nor the place.

Kevin Patton:

And I think I can reduce Zoom fatigue by reducing how many things I’m trying to take part in at one time. Oh wow. I just thought of something. You’re not listening to this episode during a faculty meeting. Are you? Hmm. Another factor that seems to play a role in Zoom fatigue is what some folks call a constant gaze that we maintain with others in a video meeting. Now, I’m a big fan of having as many folks keep their web cam on as possible. I think it’s part of the human engagement factor. When it’s my turn to present or ask a question, it’s kind of disconcerting to see that whole gallery of faces suddenly shut off. Really? They all have to go off to the bathroom at the same time? In my mind, they’re just tuning me out, which is probably not true, but this is my mind we’re talking about here, so I’m thinking those thoughts.

Kevin Patton:

I kind of like to see faces when I’m in a video meeting and when I’m presenting. But the flip side is that we tend to really focus on our own faces a lot to make sure we look like we’re paying attention and haven’t inadvertently relaxed into our resting grumpy face and don’t have mustard on our chin or headphone hair and maybe wonder whether anybody else can see that layer of dust on everything behind me. We need some breaks where we can glance out the window or look around us a little bit. And there we are staring more intently at the screen than even when we’re streaming a movie or when we’re having a live conversation with somebody one-on-one. Yeah, we look into their eyes, but we don’t stare into their eyes constantly. That’s kind of creepy.

Kevin Patton:

No, we’re kind of looking around a little bit and look at them and then look around a little bit and then look at them. But we don’t tend to do that in a Zoom meeting or a video meeting. And so that’s adding to that stress, right? So to manage this, it might work to just shut off our mic and our camera for a few minutes every once in a while, maybe even minimize the screen so we can’t look at our face or anybody else’s and just look around the room for a few minutes. To prevent watching yourself a lot, maybe try to get rid of the view of just you if you can. It depends on what platform of a webinar you’re in whether you can do that or not, but maybe you can open up some kind of window or something to hide that little screen of your face or just don’t look at it.

Kevin Patton:

Now something that I do that contributes to my own Zoom fatigue is that I find myself signing up for more webinars than usual and going to more meetings than I normally would attend. But hey, they’re now virtual so I can make it this time. Yeah. I don’t know. I think partly that’s because every organization I belong to has decided to start holding a bunch of webinars and Zoom free for alls, and I don’t want to miss out. And there are some organizations I belong to that I normally can’t attend their conferences. So this is a chance to join the fun. And there are some organizations that I don’t even belong to that they’re now having free webinars. I don’t have to join or pay or anything. And a lot of them look pretty interesting.

Kevin Patton:

Everybody is having a lot of fabulous Zoom meetings and webinars and it’s, I don’t know. It’s like when a literate person walks into a bookstore, I just want to read all the books. So what’s the answer? Well, of course the answer is to space them out as much as I can and realize that I just can’t do every webinar I see. And if it’s something that can just as easily be done another way, like on the email conversation or Slack or an online community thread, maybe I ought to try that. Zoom after all, isn’t the answer for everything. I think sometimes we act that way, it’s like, oh, well, we’ll just have a Zoom meeting. Of course, we’ll have a Zoom meeting. It’s kind of a knee jerk response. Isn’t it? Maybe we should watch that more. I should watch that when I say, “Yeah, let’s do it. Let’s do that Zoom meeting.”

Kevin Patton:

And I also want to keep in mind that my students are prone to Zoom fatigue as well. Maybe it’s not a great idea to have a web meeting during every scheduled class period, or if I have to do that because of some school policy, maybe I can break it up a little bit with, I don’t know, well, breaks, break it up with breaks. What a novel idea. Or maybe I can break it up with activities that they can do away from the meeting for a few minutes. Like, “Hey, let’s shut down for 10 minutes and go do this or go read that paragraph, or do something like that. Do some stretches. We’re talking about muscle, go do some stretches and we’ll come back in 10 minutes.” Something else is, if possible, I might want to shorten the length of my video class meetings or hold them regularly but just not during every class meeting.

Kevin Patton:

Now, if my school policy says that I must meet for the full class period every class period, well, what if I adopt a creative attendance policy that says, I’ll have the meeting open on Thursday. Sure. But all you have to do is sign in, say hello in the chat, and then sign out. Now, maybe that won’t work in your situation, but you can probably find some creative way to get around having to have a full Zoom meeting for this full amount of scheduled time that you’re supposed to have it. You probably have a lot of good ideas for reducing Zoom fatigue. Yeah, I know it. So let’s hear them. Call in on that podcast hotline. Why don’t you?

Sponsored by HAPS

Kevin Patton:

The human Anatomy and Physiology Society or HAPS has been having all these virtual town hall meetings recently, and many discussions and presentations have centered around how we can cope with pandemic teaching. In response to that need, HAPS members are busy helping us all by compiling all kinds of resources. One recent addition to the HAPS library is a tool to help select resources for remote instruction of A&P lab, including online and at home physical lab experiences. To get this new tool, just visit HAPS at theAPprofessor.org/haps. That’s H-A-P-S. And remember marketing support for this podcast is provided by HAPS.

Pandemic Heart: Stress Cardiomyopathy

Kevin Patton:

We all know that so-called the Zoom fatigue has become a new hallmark of pandemic teaching. Something else that’s becoming a thing is what I call pandemic heart. Now, nobody else calls it that, just me as far as I know, but this is my podcast and that’s what I’m going to call it. But if you get this condition, and I hope you don’t, your physician is going to tell you that you have stress cardiomyopathy, sometimes known as broken heart syndrome. You know what, before I go any further, I think this is a good time for…

Speaker 4:

Word dissection.

Kevin Patton:

Where we practice what we all do in our teaching and take apart words and translate their parts to deepen our understanding. Sometimes they’re old and familiar terms, and sometimes they’re terms that are new to us, or maybe so fresh that they’re new to everyone. The first term we’re going to dissect is stress cardiomyopathy. So the first part of that is stress, which I think we all know what stress is, right? But it’s useful to know it comes from the same root as stretch, which means tension. So that makes sense, right? Literally tension. And stress, well, it’s used here because this condition, stress cardiomyopathy is caused by significant emotional stress, such as the death of a loved one.

Kevin Patton:

And that’s what gives it its nickname of broken heart syndrome. But it can be any severe emotional or even physical stress such as the physical stress of an asthma attack, for example. So that’s stress. The next part of the word is cardio. We know that means heart. Then the next part is myo, M-Y-O, which means muscle. And then path, P-A-T-H, and then we know that means disease. And then the Y at the end means it’s a state or a condition. So cardiomyopathy then is a disease state that involves heart muscle. What some scientists propose for stress cardiomyopathy is that large burst of epinephrine released during intense stress, that is stress responses, temporarily, well, we can say stun heart cells.

Kevin Patton:

They weaken the heart cells so that the myocardium gets weaker and can’t maintain normal cardiac output. It may cause the ventricular wall to bulge out from its normal shape. Because of that myocardial weakness, it can no longer push in and push against blood, at least not as strongly. And so the pressure of that blood is bulging it out in the ventricular area. So that’s the term stress cardiomyopathy. Let’s move to our next term, and that is a synonym for this condition. It’s called takotsubo cardiomyopathy. Now takotsubo is actually two words in Japanese that have been mushed together. Takot, T-A-K-O-T, means octopus. The subo part, S-U-B-O means pot or jar.

Kevin Patton:

So put together, takotsubo is a traditional clay pot that has a narrow neck and a wide ballooning body. And you put those in seawater and an octopus looking for a nice tight place to settle in and watch everything, which octopuses like to do, my cats like to do that too. So the octopuses, they like to do this and they squeeze into the pot. And once they do that, you can now harvest the octopus. Sometimes they put bait fish in there to make sure the octopus finds that little pot or takotsubo. And that’s the shape that the heart takes on when you get stress cardiomyopathy. Because of the weakening of the ventricular myocardium, you have that bulging out of the heart wall. So that’s how they’d gotten that name or that synonym. Because of that, it’s often called takotsubo cardiomyopathy.

Kevin Patton:

Yet another name for that same condition is apical ballooning syndrome, which is pretty much what I just said when I described takotsubo cardiomyopathy. Pulling that apart or dissecting that term, apical, we have apic, which is a form of apex, which means tip or point. And so in the heart, that refers to the ventricular portion, the inferior part of the heart is the apex. The superior part or the atria, that would be considered the base of the heart. So we’re talking about the apex of the heart, not the base. And then the al ending means relating to. So it’s relating to the inferior part of the heart. And then the ballooning thing, well, let’s dissect that, it’s ordinary English word, but it’s useful to dissect it.

Kevin Patton:

In balloon or ballooning I should say, the ball part means ball, like a baseball. The -oon suffix means large. And then the ing tacked on to that in this case is making the noun balloon into an adjective. So if something is ballooning, that means it’s bulging out like a larger ball, right? So that’s ballooning. And then we have syndrome. Syn is syn, and that means together. Then drome literally means run or it can refer to a running path or a racecourse. So syndrome then, putting those word parts together means a group of symptoms that occur or run together. Refers to a group of symptoms that in this case literally occur or run together. Syndrome, run together.

Kevin Patton:

Getting back to our story. A recent study found that the incidents of stress cardiomyopathy more than doubled after the COVID-19 pandemic began. Yep. You heard that right. More than doubled from about 1.8% before the pandemic, it jumped to 7.8% after the pandemic got underway. I’m thinking that the stress of our rapid forced move to remote teaching this spring and summer, our current rush to prepare for who knows what in the fall. The uncertainty embedded in all of that, the big spice that many communities are facing right now but still planning some sort of in-person teaching and well, all that is probably causing enough stress to keep the rates of stress cardiomyopathy high or maybe even trigger them to go higher.

Kevin Patton:

Because the symptoms of stress cardiomyopathy, often including chest pain, shortness of breath, sweating, dizziness, nausea, and vomiting, weakness, and palpitations, that is the sensation of heart-pounding, mimics those of a heart attack and many folks are still avoiding emergency departments because of the pandemic. This could make the situation even worse. The good news about stress myocardiopathy is that the vast majority of those who develop it will recover in a few days or weeks, especially if they get good care and reduce their stress. Now, besides getting medical care, if we experience symptoms of acute stress cardiomyopathy, what can we do if we feel stressed and want to reduce our risk of stress cardiomyopathy?

Kevin Patton:

Well, the usual self-care that reduces stress such as meditation and other mindfulness practices. Long time listeners to this podcast know that my favorite stress reducing practice is Tai Chi, which I do every single day. That and podcasting, well, I don’t do podcasting every single day, but podcasting is kind of a mindfulness practice really. Podcasting helps me temporarily focus on something other than my classes and other than my school, and other than the stressful parts of the pandemic in the same way a pandemic journal might, which is another good self-care practice. And podcasting also helps me feel more connected to you. And we know that maintaining social connections during a pandemic helps reduce stress too.

Kevin Patton:

In fact, I’ll help you with that. Just call into the podcast hotline any time. And if you do that, we’ll all be more connected. Of course, my main point is that the way to avoid developing pandemic heart is to find what gets your mind off the stress and practice that regularly.

Staying Connected

Kevin Patton:

I have all kinds of links in the show notes and at the episode page at theAPprofessor.org/73. They’re related to everything I talked about in this episode. As I mentioned earlier, I’d really love you to connect back to me by calling in with your questions, comments, and ideas at the podcast hotline, that’s 1-833-LION-DEN or 1-833-546-6336. Or send a recording or a written message to podcast@theAPprofessor.org. I’ll see you down the road.

Aileen:

The A&P Professor is hosted by Dr. Kevin Patton, an award-winning professor and textbook author in Human Anatomy & Physiology.

Kevin Patton:

Please unplug this episode before attempting any type of repairs.

This podcast is sponsored by the

Human Anatomy & Physiology Society

This podcast is sponsored by the

Master of Science in

Human Anatomy & Physiology Instruction

Transcripts & captions supported by

The American Association for Anatomy.

Stay Connected

The easiest way to keep up with new episodes is, um, wherever you already listen to audio!

Click here to be notified by email when new episodes become available (make sure The A&P Professor option is checked).

Call in

Record your question or share an idea and I may use it in a future podcast!

Toll-free: 1·833·LION·DEN (1·833·546·6336)

Email: podcast@theAPprofessor.org

Share

Kevin's bestselling book!

Available in paperback

Download a digital copy

Please share with your colleagues!

Tools & Resources

TAPP Science & Education Updates (free)

TextExpander (paste snippets)

Krisp Free Noise-Cancelling App

Snagit & Camtasia (media tools)

Rev.com ($10 off transcriptions, captions)

The A&P Professor Logo Items

(Compensation may be received)

🏅 NOTE: TAPP ed badges and certificates can be claimed until the end of 2025. After that, they remain valid, but no additional credentials can be claimed. This results from the free tier of Canvas Credentials shutting down (and lowest paid tier is far, far away from a cost-effective rate for our level of usage). For more information, visit TAPP ed at theAPprofessor.org/education