Even MORE Test Answers | Normal Body Temperature?

TAPP Radio Episode 101

Episode

Episode | Quick Take

Have you ever really considered the actual meaning that word “normal” in the context of teaching anatomy and physiology? Is it even meaningful at all? We explore that in the context of human body temperature in Episode 101. And I give some practical tips as we continue our conversation about my open, online, randomized testing scheme.

- 0:00:00 | Introduction

- 0:00:47 | What Does Normal Mean?

- 0:08:32 | Sponsored by AAA

- 0:10:01 | What is Normal Body Temperature?

- 0:27:21| Sponsored by HAPI

- 0:29:13 | In Our Last Episode…

- 0:32:20 | Sponsored by HAPS

- 0:33:35 | Practical Tips on Testing

- 0:52:39 | What About Lab Practicals?

- 1:01:31 | Staying Connected

Episode | Listen Now

Episode | Show Notes

Nobody realizes that some people expend tremendous energy merely to be normal. (Albert Camus)

What Does “Normal” Mean?

7.5 minutes

What does “normal” mean? In this segment, Kevin asks whether that (very commonly used) term is really all that helpful.

Note: In my narration, I estimated 30% of the text in my Anatomy & Physiology textbook is the word “normal.” That was hyperbole. To make a point. That percentage is not accurate. Nor is is it “normal.”

Sponsored by AAA

1.5 minutes

A searchable transcript for this episode, as well as the captioned audiogram of this episode, are sponsored by the American Association for Anatomy (AAA) at anatomy.org.

Don’t forget—HAPS members get a deep discount on AAA membership!

What is Normal Body Temperature?

17 minutes

The “normal” discussion continues by examining ideas about what the average human body temperature is. Hint: it’s NOT 37°C. And…wait for it…it’s getting lower over time!

- A Critical Appraisal of 98.6°F, the Upper Limit of the Normal Body Temperature, and Other Legacies of Carl Reinhold August Wunderlich (Mackowiak article in JAMA) my-ap.us/3tQd8eG

- Decreasing human body temperature in the United States since the Industrial Revolution (article from eLife) my-ap.us/3AltIFI

- eLife Podcast Episode 63 (segment 4 features an author of the cited eLife article) my-ap.us/3tOQqUc

- Introduction to A&P (Kevin’s student outline that covers body temp issues) lionden.com/ap1out-intro.htm

Sponsored by HAPI Online Graduate Program

1.5 minute

The Master of Science in Human Anatomy & Physiology Instruction—the MS-HAPI—is a graduate program for A&P teachers, especially for those who already have a graduate/professional degree. A combination of science courses (enough to qualify you to teach at the college level) and courses in contemporary instructional practice, this program helps you be your best in both on-campus and remote teaching. Kevin Patton is a faculty member in this program at Northeast College of Health Sciences. Check it out!

In Our Last Episode…

3 minutes

A brief recap of the two previous episodes, which prepares us for some follow-up discussion.

- Quizzed About Tests | FAQs About Patton Test Strategies | TAPP 99

- More Quizzing About Kevin’s Wacky Testing Scheme | Book Club | TAPP 100

Sponsored by HAPS

1.5 minute

The Human Anatomy & Physiology Society (HAPS) is a sponsor of this podcast. You can help appreciate their support by clicking the link below and checking out the many resources and benefits found there. Watch for virtual town hall meetings and upcoming regional meetings!

Practical Tips on Testing

19 minutes

All kinds of practical tips on using randomized tests, why we (especially) need transparency when using them, making test items, formats, student-generated test items, and more.

- Teaching in Higher Ed podcast with Bonni Stachowiak Episode 350 Ungrading with Susan D. Blum (includes a comment by Bonnie regarding adopting radical strategies in disciplines with board exams) my-ap.us/2WY4hLG

- Testing as Teaching (online seminar containing info on my use of Respondus test-editing software)

- Test Question Templates Help Students Learn | TAPP 70 (episode with Greg Crowther explaining his TQT system)

- Weight Stigma! The Difficult Cadaver | Journal Club Episode | TAPP 93 (episode with Krista Rompolski and a discussion of weight bias among health professionals)

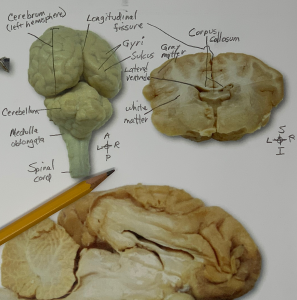

What About Lab Practicals?

8.5 minutes

More on how similar test items can cause issues for students who don’t carefully examine each test item. Can open, online, randomized testing be used as a strategy to help students prepare for their lab practicals? Maybe even supplement or replace lab practicals during a pivot (like, um, er, a pandemic)?

Need help accessing resources locked behind a paywall?

Check out this advice from Episode 32 to get what you need!

Episode | Captioned Audiogram

Episode | Transcript

The A&P Professor podcast (TAPP radio) episodes are made for listening, not reading. This transcript is provided for your convenience, but hey, it’s just not possible to capture the emphasis and dramatic delivery of the audio version. Or the cool theme music. Or laughs and snorts. And because it’s generated by a combo of machine and human transcription, it may not be exactly right. So I strongly recommend listening by clicking the audio player provided.

This searchable transcript is supported by the

This searchable transcript is supported by the

American Association for Anatomy.

I'm a member—maybe you should be one, too!

Introduction

Kevin Patton (00:00:00):

The French philosopher and author, Albert Camus, once wrote, “Nobody realizes that some people expend tremendous energy merely to be normal.”

Aileen (00:00:13):

Welcome to The A&P Professor, a few minutes to focus on teaching human anatomy and feel physiology with a veteran educator and teaching mentor, your host, Kevin Patton.

Kevin Patton (00:00:28):

In this episode, I ask, what is “normal” anyway in the context of body temperature? And I give some practical tips for implementing an open, online, randomized testing scheme.

What Does “Normal” Mean?

Kevin Patton (00:00:47):

I’ve been thinking about this question a lot lately, and that is, what is normal body temperature? Now, you’re probably thinking, well, it’s 37 degrees Celsius, right? Which is 98.6 degrees Fahrenheit. Everybody knows that. Well, it turns out that’s not right. Well, maybe it’s kind of right. Which leads to another question, and that is, what is normal? What do we mean by “normal” when we apply that to body temperature? Well, I’ve been thinking about this lately for a few reasons.

Kevin Patton (00:01:20):

One is, I’ve been going up to visit my mom a lot in her assisted living facility. And when you check in these days, you have to align your eyes up with this little mirror image in a machine, and then it shoots a beam at your forehead, and then it displays what your body temperature is. And my body temperature is always past the screening test. I don’t know what would happen if it was too high. I don’t know if alarms would go off and security would come rushing at me or whether some bared gate would drop down in front of me or what exactly would happen, but it hasn’t happened yet.

Kevin Patton (00:01:58):

But I do take note of that body temperature and I have noticed that it’s always with the range that I expect it to be. But you know what? It’s never 37 degree Celsius. Well, the main reason it’s never 37 degree Celsius is it doesn’t print out in Celsius scale. It prints out in a Fahrenheit scale, but it’s never 98.6 degrees Fahrenheit. It’s always lower than that. And you know what? That’s okay because, well, I get in to see my mom, but also it’s expected for me. In other words, I know what my usual range is. I’m going to come back to that in a second.

Kevin Patton (00:02:37):

But there’s another reason why I’ve been thinking about this lately, and that is…

there’s new research that’s come out not very long ago on human normal body temperatures that really does affect our discussion in A&P. I think it can affect our discussion in A&P. I’ll tell you about that new research in a minute. But another reason I’ve been thinking about it lately is I’ve been dealing with the word normal a lot wearing my hat as a textbook author. Let’s start with that. My team has been revising our two-semester A&P book. It’s going to be coming out in November of this year. So, we’re wrapping it up right now.

Kevin Patton (00:03:20):

One of the things that we’ve been doing that’s really taken a lot of time and mental energy is searching for words and phrases that need to be re-examined in the book. We need to make sure that we’re saying things that we mean that couldn’t possibly harm people by giving the wrong impression. And one of the words that we’ve been focusing on is normal because we throw that around a lot. And of course, when you use the word normal a lot, that implies that if it’s something that we’re talking about is not normal, then it’s abnormal. That can be interpreted or received in a variety of ways that are not intended.

Kevin Patton (00:04:04):

So, when we talk about normal body temperature or normal blood pressure or normal anything, normal stature, normal body weight, normal body mass, when we talk about things like that and imply that anything outside that number is abnormal, that not only could be harmful to users and whatever patients or clients that those users end up working with, it’s also probably not accurate. It’s probably not helpful. So, as we’ve gone through the book, I think that probably 30% of the words in my textbook are the word normal. I mean, I didn’t realize that I use that word normal so much.

Kevin Patton (00:04:49):

I looked around and a lot of people use that word normal and I use it in my teaching. So, that might be a good practice for us or a good exercise for us as instructors to look at the materials we create, look at the conversations we have, the lectures, the discussions and tutorials and so on that we have and think about what we’re saying. Do we use the word normal a lot? Because a lot of times, we found in doing this exercise in our book that we don’t even need that word there. It actually makes much more sense, it’s much more accurate if we just drop that word normal.

Kevin Patton (00:05:27):

And if we need an alternative term, there’s usually an alternative term that is much more helpful and meaningful than the term normal. Yeah, normal is been on my mind a lot and the idea of a normal body temperature in particular. So, this idea of normal body temperature, let’s talk about that. Now, that’s something that I’ve been calling out in my classes, in my books for decades. That is, what do we mean by normal when we’re talking about body temperature? First, I suggest that what we’re calling normal in terms of body temperature can change for a lot of reasons. That is, our body temperature is not always normal if that’s the term we want to use. What can change body temperature?

Kevin Patton (00:06:20):

Well, there are those transient inflammatory responses that our body experiences, there are chronic inflammatory conditions that we might have, where we are in our lifespan, our life cycle. Are we infants? Are we children? Are we adolescents? Are we young adults? Are we old adults? Are we old, old adults? Where are we in that span because that’s going to affect our temperature. What about short-term reactions to ambient temperature? What about all those hormonal and metabolic cycles and events that affect temperature, exercise that effects temperature? What time of day it is that effects temperature?

Kevin Patton (00:07:03):

Another thing that affects temperature is, where on or in the body we measure the temperature? That matters. That affects what the temperature reading or measurement is going to be. Is it the temperature inside our mouth, our oral temperature? Is it rectal temperature? Is it on the forehead like I mentioned a moment ago when I go to visit my mom? Is it in the ear? Yeah, there’s lots of places where you can measure the body temperature and that affects that reading. Temperature is going to be different in different areas of your body in an instant.

Kevin Patton (00:07:38):

But then you add in all these other factors that I just listed, holy smoke, there are a lot of factors and variables that affect what your body temperature is going to be in any one moment. Secondly, and it’s often related to this first thing about the variability, is the fact that we do sometimes reset our temperature setpoint, don’t we? Like when we have a fever. What that basically is doing is resetting our body’s setpoint for temperature to a new, temporary, higher level. And that new temporary, inflammatory setpoint may be a degree or more higher than it typically is under resting, healthy conditions. I’m going to continue this story in just a moment.

Sponsored by AAA

Kevin Patton (00:08:32):

A searchable transcript and a caption audiogram of this episode are funded by AAA, the American Association for Anatomy. If you want, or maybe you need captions, those caption audiograms are available at each episode page. Or you could subscribe to The A&P Professor channel in YouTube and get them that way. And those transcripts, they’re likewise available at each episode page and both the captioned audiograms and the transcripts can also be accessed by links in the show notes in most podcast apps that support links.

Kevin Patton (00:09:15):

Now, I’ve just started posting transcripts in the TAPP app as well. The TAPP app is the free, standalone app just for this podcast. When listening to an episode in the TAPP app, just click the little gift box icon near the top of the screen and you’ll get a PDF copy of the transcript. It’s a present. It’s like your holiday present. You get this transcript when you click that little gift box icon. Now, all that transcripting and captioning is supported by our friends at the American Association for Anatomy and you can visit them at anatomy.org.

What is Normal Body Temperature?

Kevin Patton (00:10:02):

So, when we say normal body temperature, don’t we really mean typical body temperature or maybe healthy body temperature? Sometimes, maybe calling it the setpoint temperature works best. It depends on the context. What are we really talking about in that moment is going to determine what alternative term for normal might work better than the word normal. Using the terms normal and it’s converse abnormal hardly ever tells us anything we really need to know. It can also have this unexpected effect of making people feel bad, and I don’t want to do that.

Kevin Patton (00:10:45):

Physicians take an oath to cause no harm, and I think as teachers, we need to hold ourselves to that as well, even if it’s harm that I’ve only recently become aware of. And maybe it affects me too, but I know it affects other people, and I don’t want to do that in my teaching or in my textbooks. I want to do no harm. Now, I know what you’re thinking, and I think it too. And my students often say it to me when we discuss this idea. And as I said, we do discuss in my class, we’ve done that for a long time.

Kevin Patton (00:11:20):

They will say to me, my students will say to me, and I will sometimes say to myself, “Well okay, if we use the term normal temperature, what we mean by that is, what we need to know to tell if we ourselves or our patient, if that’s the case, or a family member, if they’re abnormal or not… ” Okay, we’re back to using the word normal and abnormal and the connotations that are unintended. But I mean, we do want to know, are things out of the ordinary? Because if they’re out of the ordinary, then maybe we better check into it more.

Kevin Patton (00:11:56):

That’s why it’s useful to have a normal body temperature. What I think is not useful is to use the word normal or at least use normal in quotes and that’s going to be only interesting and useful to a beginning A&P student when we’re to dissecting this out and to other people who are interested in the physiology of the human body. When we’re using that term, we’re usually referring to the mean or average temperature for humans. And because it’s a mean value that is a statistical mean or an average, it is useful in a population, but not so much when we’re trying to apply to an individual person.

Kevin Patton (00:12:42):

That’s why it’s important for a person or individual to know their typical or healthy body temperature under varying conditions. And it won’t be one number. I mean, you’d have to do your own pretty thorough, statistically valid test on yourself to come up with one mean number. And I don’t think with that one number it’s all that useful, because it varies so much. So, in healthy people, scientists tell us that it varies about half a degree Celsius or about 0.9 degrees Fahrenheit throughout the day. And that’s on average, so it could be a little bit more, a little bit less than that in a particular individual.

Kevin Patton (00:13:27):

And the numbers that I come up with as a range are not likely to be the same as the range that you come up with for yourself. But it is a range. I think that range is much more valuable. We can call it a setpoint range rather than just setpoint to imply the fact that it is a range and that’s what’s helpful to us. But even so, the so-called normal or mean or average temperature, well, it’s still good as a ballpark number when you don’t know that other person’s typical temperature range, right? Having a “normal” body temperature like 37 degree Celsius, it’s something, it’s something we can use.

Kevin Patton (00:14:09):

But the thing is, it’s just so hard to keep from thinking of it as a hard number written in stone for each of us. That is that it’s a hard number that applies to every single one of us. I think something that we have to work on ourselves and help our students work on is breaking out of that idea. It’s a mindset thing. We need to have a mindset that uses typical patterns to understand basic structures and mechanisms while at the same time realizing that those patterns vary. They’re not written in stone. They vary from one person to another, and even within that person under varying conditions or even different times of the day.

Kevin Patton (00:14:58):

But another thing that I want to bring up here is, okay, 37 degree Celsius, it’s the average number for the human population, so we can still use it as a ballpark number. And that’s a good storytelling thing anyway, right? We want to pick an average number and stick with it. As we go throughout the story, throughout a semester, or two-semester sequence, and we keep coming back to early parts of the story, we want to remember what number we used. Why not just use 37 degree Celsius? That’s okay, to use the mean number. But the thing is, that’s not right. That is not the mean number or average number for the human population. We’re not really using the correct numbers. Not exactly. So, this takes us back to the olden days.

Kevin Patton (00:15:48):

Once upon a time, a man named Carl Wunderlich did this amazing and thorough and accurate study of human body temperatures and he found that the oral human body temperature has a mean value of 37 degree Celsius and 98.6 degrees Fahrenheit. That’s where those numbers came from. Everybody believed Carl Wunderlich because Carl Wunderlich laid out some really good data. And it really was good data. It was not bad data, it was not poorly measured, it was not badly analyzed statistically. I mean, it was a good experiment. He looked a ton of people, or maybe it was 1.2 tons, I don’t know. I don’t remember off head, but it was many, many people.

Kevin Patton (00:16:40):

Okay, that was the olden days. Now, 1992 rolls around and a guy named Philip Machowiak and his colleagues Wasserman and Levine, they did a follow-up study and they’ve found the average temperature to be a little bit different. Their average temperature was not 37 degrees Celsius or 98.6 degrees Fahrenheit. This new number was 36.8 degrees Celsius or 98.2 degrees Fahrenheit. Let me say that again; 36.8 degrees Celsius, 98.2 degrees Fahrenheit. So, that’s a little bit lower than wonder licks numbers from 1868. It’s almost a century and a half earlier.

Kevin Patton (00:17:29):

And since we’re looking at the Machowiak numbers right now, their upper limit of normal body temperature that they analyzed was about 37.7 degrees Celsius. So, normal temperature, upper limit of normal. So, here we are getting back to the range. The upper limit was about 37.7 degree Celsius. That works out to be 99.9 degrees Fahrenheit. Another thing they found was the daily variability of temperature ranged about 0.5 degree Celsius. And of course, this is on average, and that works out to be 0.9 degrees Fahrenheit.

Kevin Patton (00:18:13):

Those are the numbers that I’ve been giving my students since the early 1990s as part of a discussion similar to what I’m talking about right here, right now. Now, my textbooks, it’s not really appropriate to dive so deep into the ins and outs of what we used to think and what we think now and all this history and so on. I mean, that makes for a nice discussion in my A&P class. And that’s the place where I choose to talk about this variability of body functions and structures, or at least introduce it for the first time, and so I do that very early in the course. But you make your choices about where you want to have that conversation.

Kevin Patton (00:18:56):

That’s not up to me as a textbook author to determine that part. And if I go dive that deeply into every concept in an A&P book, it’s going to be unreadable and it’s certainly not going to engage a beginning level student. That’s why there are details that are left out of textbooks. And of course, we can always argue about this coverage here or that coverage there as to whether it doesn’t have enough detail or whether it has too much detail. Those are choices I make and my team makes based on our teaching experience. It may not align exactly with yours, but there’s going to be no one textbook that does that.

Kevin Patton (00:19:39):

So, you’re going to be using the textbook that aligns most closely with the choices you make about content and how that content is presented. When I make those choices, I also have to realize that the rest of the world around me, maybe for Philip Machowiak and his friends, these other people think that 37 degrees Celsius is the right number. So, you have to overcome that obstacle as well without really coming across as being defensive.

Kevin Patton (00:20:14):

So, I mean, just to give you an idea, the way I cover it in the textbook, here’s one of several passages that refer to body temperature and it states… it meaning body temperature, it hovers close to a setpoint of about 37 degrees Celsius, perhaps increasing to 37.6 degree Celsius by late afternoon and decreasing to around 36.2 degree Celsius by early morning. Now, that word about or around, I used both of those words in that sentence, those are intentionally vague. And the copy editor sometimes, we debate about this a little bit, because a copy editor, they want to make the writing flow very simply and evenly and directly.

Kevin Patton (00:21:10):

And it’s indirect to say about 37 degrees. So, they want to strike out about and say, “Well, just go ahead and say it, it’s 37. Be confident.” And I’m like, “No, I want to be intentionally vague.” So, when I use the terms about and around… And take a look at your textbook sometime and see where the author is being vague or is being specific and direct, because sometimes that vagueness, probably every time, that vagueness is about offering some wiggle room there, allowing it to be a little bit wobbly so that the reader doesn’t come across with the idea that that 37 degree Celsius is written in stone, that’s what it is.

Kevin Patton (00:21:53):

But if you say about 37 degrees, then that’s going to emphasize that variability among individuals. At least that was my attempt right here. Usually, when I’m intentionally vague, I’m trying to allow for additional content if the instructor wants to include that in their course. And that’s a dilemma faced not just by textbook authors, it’s faced by we faculty who are teaching A&P. We have to adjust our story and how many rabbit holes we go down and how far we go down those rabbit holes, because sometimes going down the rabbit holes is as interesting and engaging, and sometimes it’s just confusing.

Kevin Patton (00:22:35):

And we have to make those choices and we have to tailor our story and tweak our story. So, that’s something that we should be thinking about as instructors, is how we do that and whether we should be doing it in this case or that case. When I do it, well, that is when I’m vague, that allows for both the newer, more accurate mean body temperature for humans and it also allows for variations among individuals and it also allows for variations within an individual. So, then the next question is, why is that new number for average human body temperature a bit lower than the old number?

Kevin Patton (00:23:20):

Didn’t I just say that Wunderlich’s numbers were really good? Are we better at science now? Do we make measurements better? Do we make thermometers better? Do we do statistical analysis better than we did before? That’s a mental trap I’m always falling into. That is, I always think that whatever we’re doing now or recently is way better than we did 10 years ago or 50 years ago or 150 years ago and certainly more accurate or better than 200 years ago. But you know what? That’s not always true. They made really good thermometers back then and I suspect that the thermometers Wunderlich used are way better than the thermometer I bought at my local pharmacy.

Kevin Patton (00:24:00):

So, it turns out that’s not it, that’s not what it’s about. It really is lower these days. That’s based on new research that came out. It was published by a team led by Myroslava Protsiv and published last January in the online journal, eLife. And they worked this out. They worked out that it’s actually decreasing over time. So, they went back many decades. They went back to, well, before the time of Wunderlich and using these large sets of data that they had from like union army veterans for example. They had huge numbers of data, they had several cohorts that they looked at with huge numbers, and they did a lot of experimental weeding out of data that really was skewed and things like that.

Kevin Patton (00:24:51):

And you can read the article. I have a link in the show notes at the episode page and you can read the whole article and see what they did exactly. But they worked out that it has been decreasing over time. That probably explains the difference between the 1868 published numbers and the 1992 published numbers, because now we have something to link those up and see what’s happening. But why is average human body temperature decreasing? Well, the current hypothesis… And they looked at several hypotheses and rejected them in this more recent paper.

Kevin Patton (00:25:30):

But the hypothesis that they think holds the most weight, and of course more research is going to need to be done, but they think it has to do with the incidents of inflammation decreasing over time. For example, there are less infections in the population, especially undetected infections, in the population now than in the 1860s and ’70s and ’80s and so on. That makes some sense, right? Also, there’s an increased use of anti-inflammatory therapy, such as anti-inflammatory drugs. Sometimes, we take those when… Man, we don’t really need to. I mean, they’re available over the counter.

Kevin Patton (00:26:11):

Sometimes we take them because we think we’re going to have a headache that day or something, “Oh, yeah. It’s that class again.” Or, “Oh my gosh! A faculty meeting. Give me some ibuprofen before I go.” So, sometimes we make some questionable choices about those anti-inflammatories. But what’s that going to do? It’s going to decrease our temperature quite possibly when it wouldn’t have otherwise, because maybe there was a little bit of inflammation or something going on that we didn’t even realize was happening.

Kevin Patton (00:26:40):

So, that hypothesis makes a lot of sense. Whether it’ll turn out to be true or be the only factor involved, time will tell and more experimentation of course is needed to tell. So, I just wanted to share the pain of my recent reckoning with the concept of normal, which clearly is not exactly a word that describes me or anything I do, but it turns out it doesn’t really help any of us understand anatomy and physiology very well, at least in my opinion.

Sponsored by HAPI

Kevin Patton (00:27:21):

The free distribution of this podcast is sponsored by the Master of Science in Human Anatomy and Physiology Instruction, the HAPI degree at Northeastern College of Health Sciences. Now, you may wonder what free distribution really is. Aren’t all podcasts free to listen to. Well, there are some podcasts that require a paid subscription, but it’s true that most podcasts are free to listen. But they’re not always free to distribute. Sure, there are a few free distribution services out there also called syndicators, but that’s not a good business model, giving away your service for free. So, most of those really don’t last very long. And those that do don’t really distribute the podcasts everywhere.

Kevin Patton (00:28:16):

My syndicator does that and they also provide an optional app. So, someone who doesn’t really know where to go to listen to this podcast can just search for The A&P Professor, or my name, Kevin Patton, in their devices app store and then they’re ready to listen. Everybody knows how to download an app. That fee for the syndication on all the servers and electricity and IT support and everything else that that requires plus the overhead for making the app available for free is what the HAPI program supports in case you are wondering. Find out more about this online graduate program in A&P instruction at northeastcollege.edu/hapi. That’s H-A-P-I.

In Our Last Episode…

Kevin Patton (00:29:14):

So, yes, once again, I’m going to be talking about that crazy scheme I have of offering online, open, randomized tests in my A&P course. This all started back in episode 99, which was called Quizzed About Tests: FAQs About Patton Test Strategies. That’s where I answered some questions that were phoned in on the podcast hotline by my friend, Jerry Anzalone. And just a brief recap of what we talked about in episode 99, and that is, I talked about how I give tests more frequently than it’s typical. I make most of the tests online tests. I make those online tests, open book, open everything tests.

Kevin Patton (00:30:02):

I allow multiple attempts. In my regular A&P courses, I allow three attempts with the highest score going to the final course grade. All the tests have randomized question sets, meaning that every attempt is different than nearly any other. In the following episode, I gave some pretty huge numbers about how that works out. In episode 99, I talked about how all tests are cumulative. That is, all tests cover everything covered thus far in the course. I also talked about the fact that I give a pre-test before we start each new module. The pre-test is not cumulative. It has only one attempt and it’s scored so that students can see their corrected responses.

Kevin Patton (00:30:53):

But it does not affect the final course grade. They cannot access the module resources until they complete the pre-test though. That was a summary of what we did in episode 99. In episode 100, which was called More Quizzing About Kevin’s Wacky Testing Scheme, I continued the conversation by talking about some questions and comments, or at least things inspired by questions and comments, on that episode 99 that came before it. So I thought, well, why not? These ideas have come up, these questions have come up, and so why not just dig right in right away while it’s fresh in everyone’s mind?

Kevin Patton (00:31:36):

So, I did that and that included things like, do these wacky strategies really work in all courses, even in graduate or professional programs that culminate in a board or licensing exam? And I talked about test integrity and how that might impact these testing strategies. I talked about whether open tests are really effective or not as opposed to closed tests, which are more traditional. And I mentioned that I had more to talk about in the next episode. And you know what? This is the next episode. So, here goes.

Sponsored by HAPS

Kevin Patton (00:32:20):

Marketing support for this podcast is provided by HAPS, the Human Anatomy and Physiology Society, promoting excellence in the teaching of human anatomy and physiology. Now, how does HAPS support that excellence? Well, one of the many ways is to organize virtual, one-day conferences throughout the year. There’s one coming up very soon. I mean, like any day now depending on when you’re listening to this, where I’ll be one of the main speaker.

Kevin Patton (00:32:52):

Now, I’m going to be talking about nine or 12 or 20 strategies, depending on how you want to count them, on how to help our students see and learn connections between isolated facts in our course and how to apply them to practical scenarios. The other main speaker is my friend, Tom Lehman, who will be updating us on the physiology of marijuana and what we can tell our students. You want to register for that? Just go visit HAPS at theAPprofessor.org/haps, that’s H-A-P-S, and click the events tab.

Practical Tips on Testing

Kevin Patton (00:33:35):

Back in the previous episode, that is episode 100, I quoted, or I should say paraphrased, Bonnie Stachowiak, who’s the host of the podcast called Teaching in Higher Ed, when she said that no matter how we teach or how our students learn of the concepts of our course, what makes a person prepared for a board exam is that they’ve learned. It’s the learning that’s important for being prepared, not the specific strategies we’ve used to become prepared.

Kevin Patton (00:34:09):

So, to follow up on that and after some more reflection, I’m thinking that my proposed scheme that includes more frequent tests, open online tests with randomized question sets that allow for multiple attempts of each test by providing a unique version of each test or each attempt, well, all that gives the extra, spaced retrieval practice that makes it more likely that our students will retain what they’ve learned and retain it in their long-term memory. In other words, I think our traditional way of testing that is giving infrequent, closed, high stakes tests each on a different set of concepts with perhaps a cumulative final exam and only that promotes maybe only short-term learning.

Kevin Patton (00:35:08):

I’m thinking that truly long-term learning requires the addition of frequent practice that the scheme I described in the last couple of episodes provides. Now, moving on to some of the practical issues and concerns of doing tests the way I do them, let’s cover a few you different points. And again, I’m trying to be practical here. Let’s say you want to experiment with one or the other of the things I’ve described so far, well, okay, here’s some things that I’ve learned the hard way about best practices, and in many cases, worst practices that you might want to avoid.

Kevin Patton (00:35:48):

For example, there are some issues involved with these randomized test items. For example, in an earlier episode, I was trying to calculate how many different versions of a test you can get by randomizing things, and I said, okay, let’s say you’re using some multiple choice items and let’s say each of those items has five choices. That’s what I used as an example. But of course, in a learning management system, you can have items that have fewer or more choices, but let’s say five choices. So, one of the things you can do is set the learning management system so it randomizes those five choices.

Kevin Patton (00:36:29):

Let’s say one person gets a test attempt and it has that test item on it and it has A, B, C, D, and E, it has the choices in a certain order. Another person who gets the very same item get pulled out of the test bank on their test, that A, B, C, D E is going to be different. There’s 120 different variations with five choices of what order those choices could be in. That’s a part of the randomization. But here’s something that I didn’t think about before I start giving those tests, and that is, that you can’t use test items where one of the choices is, all of the above, or one of the choices might be, A and B are correct, or B and C are correct, or something like that.

Kevin Patton (00:37:15):

Now, I’m not a big fan of using that kind of a choice anyway. There are other kinds of questions that can do that better than a multiple choice in my opinion. At least that’s my style. So, I don’t tend to do that. But I did a couple of those, and of course, when that gets randomized, if their first choice is all of the above, not every student is going to figure out that that means all of them. So, you could change the wording and say, all of the choices listed here are correct. Then no matter where it shows up in the order, that can still be the correct answer, if in fact that that’s the correct answer.

Kevin Patton (00:37:53):

So, there are ways around it that way. I think it’s better just not to write test items like that, that have those kinds of things. But I’m telling you, that could be a problem if you don’t think about it ahead of time. Another issue that I’ve run into with this kind of randomization within a test item is that I’ve had students say, “Look, I got this very same test item on a previous attempt and I found out what the right answer is or maybe I did it before and I got the right answer. And the right answer was B, B was the right answer.

Kevin Patton (00:38:30):

And I saw that it was the same question on my second attempt and I knew B was the right answer, so I answered B and now it’s marked wrong. So, how can that possibly be marked wrong because it was B on the first attempt?” Then I asked him to look at the choices between the two versions and then they’re like, “Okay, I see. They’re mixed up. They’re not the same order of choices.” So, what they were doing was assuming that it was exactly the same question without reading through to see that, well, yeah, the stem is the same, the question itself is the same, but the choices given are not the same, at least they’re not in the same order.

Kevin Patton (00:39:16):

So, B has now moved down to D, maybe let’s say, or maybe it’s moved up to A. So, what that means is they have to really examine each and every test item. So, they’ll often ask me, “Well, can you change my grade?” “No, that’s a very good learning experience. You learned a lot on that test item. I think I’m going to leave it stand and next time you run across that, you’re not going to just assume what the right answer is.” I know you’re probably thinking, because I’ve questioned myself about this too, is, aren’t I being too much of a hard case about this? Just like, “Oh, give them the points.” Okay, maybe. Maybe I can give them the points.

Kevin Patton (00:40:03):

I don’t think that’s really very helpful for anything, but they got it wrong, and if it’s wrong, it’s wrong. I mean, if it’s a matter of them passing the course or not, I certainly revisit that. But just one test item? Come on. And I really do think it’s a good learning experience, but not just for taking online tests. And that’s a useful skill. I mean, especially in this day and age, and I think it’s going to be even more important as time goes on in the near future that students are skilled at taking online tests. But setting that all aside, many of my students are going to go on and be healthcare professionals.

Kevin Patton (00:40:40):

They’re going to be caring for patients or other clients and I don’t want to walk into their scenario, into their clinical situation and they glance at me and assume they know what’s wrong with me or what needs to be done with me or whatever. I mean, we see that happen all the time in healthcare. We see people who are overweight walk into a physician’s office with some complaint and the physician doesn’t even listen to their complaint. I bet if hard press, they cannot repeat back anything about what the patient just told them because they see overweight and they think, “Well, yeah, anything you have here is because you’re overweight.

Kevin Patton (00:41:18):

You need to lose weight and then you’ll feel better. Come back in six months and we’ll talk more about it.” Yeah. Really? Come on. That is a bias that we’ve talked about in this podcast before and HAPS has been planning some town hall meetings about weight bias, so there’s a good tie in there, right? There’s something that really is being discussed right now in the A&P teaching community, is weight bias. But there’s all kinds of other biases too that we have. Sometimes, well, okay, high blood pressure must be this, high body temperature must be that, and we fall into this lazy thinking. All of us do that.

Kevin Patton (00:41:59):

I mean, I do that with my students too. Well, I’ll have a student come in, say they didn’t do so well on the test, and I automatically assume they didn’t put enough time into it. You weren’t careful, that’s why, the common list of things. Well, you know what? A lot of times that turns out to be true, but you know what? That reinforces my bias. So, when I run across a student who says, “No, I really did work hard. I really did put a lot of hours and I really was careful,” and all that. Then you find out, well, they’re dyslexic and maybe they didn’t even know it.

Kevin Patton (00:42:32):

Or they had some other issue that maybe they were aware of, but didn’t realize it was affecting their tests, and that I certainly was not aware of. So, that lazy thinking isn’t going to help that student, is it? Not only that, it’s going to maybe promote that lazy thinking later on in their career and I don’t want that to happen because they could be taken care of me. So, it’s yep. Once again, it’s all about me. So, there’s that. That’s something to watch out for too. I tell this, I’m transparent. I tell the students all the time, “This is going to happen to you.”

Kevin Patton (00:43:08):

They either don’t believe me, or more likely… And here I am doing the lazy thinking again. I don’t know what they’re thinking, but I suspect a few of them are thinking, “Yeah, yeah, yeah. I’m not going to do that.” Then they do it, they fall into that trap, and then they come back later and like, “How did I do that? How did I fall into that trap?” So, I do warn them ahead of time, so it’s not like they’ve not been warned. But often, like anything, and I’m the same way, I don’t really learn it until I step into that trap and have to be extracted from it. Okay, another practical bit of advice is building a test bank.

Kevin Patton (00:43:44):

Now, how is that actually done? One thing I’ve already meant previously, actually in way past episodes as well, is I built my original test bank over the course of a year, that is, two semesters. I did that by coming home from campus every day and spending 20 minutes. I had a chunk of time set out, 20 minutes I would work on test items. Next day, 20 minutes. So, I did that Monday through Thursday and I was always staying just ahead of the students in terms of when they had to take a test. Then every year after that, I would go back and look through it and add some items so my test bank was larger.

Kevin Patton (00:44:25):

Maybe take out some items that students were finding problematic or more likely just rewrite the item so it was a better, clearer item that zeroed in more on what I was really trying to ask the student. That’s part of the practical part of it. I’ve also mentioned, I believe I mentioned in way past episodes, that I use a piece of software called Respondus, which a lot of campuses have a site license for. So, you might want to check into that. Decades ago when I first bought mine and it was a lifetime license. So, it’s really worked out for me because I’ve used it a lot. It really didn’t cost that much and so I went ahead and bought my own license and started using it.

Kevin Patton (00:45:15):

Respondus is a program. Now, you may be familiar with Respondus LockDown Browser that’s used to try and keep a lid on test integrity and anti-cheating and so on. Before they had that, they had something that’s just called Respondus. And what that is it’s a test item editor. For me, I find it way easier to use than a learning management systems, built-in test editor. Now, a lot of these test editors and the various learning management systems have gotten a lot easier to use. So, if I was going to go back in and create a test bank, I’m not so sure I would use Respondus anymore. I would have to compare them with my learning management system and see which one would be easier to use.

Kevin Patton (00:46:04):

And what I mean by easier use is which one would have a faster workflow because that’s important, right? So, I might not end up using Respondus, but I want to mention it as a possible, available option. Then Respondus, what you do is you have to set it for… Am I going to be using Canvas? Am I going to be using Blackboard? Am I going to be using Moodle? Am I going to be using D2L? What is it I’m going to be using? Then it’ll set it up and only allow you to ask the question types that are available in that learning management system.

Kevin Patton (00:46:37):

Then when you’re all done, you can either manually or automatically upload that test bank into your learning management system, into your course, in that learning management system. But I also want to mention that there’s another use of Respondus that’s very handy too, and that is if you ever switch learning management systems. Let’s say you move to a different school, but you want to use your test bank, or let’s say your school decides to change what learning management system they use. Well, Respondus is a great tool because you can download everything.

Kevin Patton (00:47:07):

Even if you didn’t use Respondus originally, you can download your test bank from your learning management system, flip the switch over to the other learning management systems. So, you can switch from Moodle to Canvas for example, and now they’re all in Canvas format. Now, there might be a handful of questions you will come back and say, “No, can’t use that one or this one or this one,” because there’s no such format in your new learning management system. Or we did this, we compressed your choices or I can’t remember what the things were. But usually, there’s only a handful of those. Then you can deal with those in short order.

Kevin Patton (00:47:46):

Then you take that and you upload that to your new learning management system. That can really get rid of a lot of pain of changing to a new learning management system. And I’ve done that a bunch, at least five times, it’s probably more. I now don’t really have the kind of panicking episode that I did when I first had to do that, especially with these large test banks, because I know that, number one, I’ve lived through all these other attempts, so I can’t be that bad. Secondly, I know I have tools like Respondus that can make the hard part way, way easier. So, I just wanted to mention that. It’s R-E-S-P-O-N-D-U-S, Respondus.

Kevin Patton (00:48:23):

Another thing to consider though that goes along with that is think about the fact that there are many different question formats. So, one of the things this process led me to was to exploring the pros and cons of using different kinds of formats within a learning management system. And I found that there are some things that can really lend themselves to this format more so than those other formats and this other concept. Yeah, that would be a really good “put in order” question or “rearrange in the correct order” question. Here’s a good labeling type item and so on.

Kevin Patton (00:49:02):

So, I have found that exploring the different formats, even those that you’re not familiar with, go ahead and explore them, play around with them a little bit, and I think you’ll make some pleasant discoveries when you do that. It also means you have more flexibility in terms of testing at different levels of thinking. So, when we think about Bloom’s taxonomy or other models of student thinking and we’re trying to pull them out of the just basic memorization or identification of facts and pull them up into different kinds of application and evaluation and so on, sometimes that’s easier to do if we break out of our mold of having just multiple choice items and we go into some of these other style of items.

Kevin Patton (00:49:53):

Another thing that you might want to think about when you’re building your test bank is something that I did just accidentally a couple of times when students suggested this themselves. So, it came from them rather than for me. But something that I think would really be a good idea is to consider letting students contribute to the test bank. Now, of course, there’s always the possibility that students are going to write a bad question, an unclear question, or they’re going to write a question that ends up all wrong or reflects thinking that’s all wrong, but there are various ways to get around that.

Kevin Patton (00:50:30):

I mean, the most obvious one is that you don’t use them until you make sure they’re correct, and so you might have to take a student item and really massage it quite a bit, or you might end up having to throw out some of them and do it that way. But there’s also collaborative things you can do in a group of students where they test each other and work out those kinks themselves as students. And you may remember, and I think this would be a great tie-in, a great dovetailing of ideas here, is back in episode 70, my friend, Greg Crowther, came on the program and talked about a paper he had published in HAPS Educator about a technique that he was developing, has developed, called TQT, which stands for Test Question Templates.

Kevin Patton (00:51:18):

Now, he doesn’t use it exactly this way, but I think it could be used this way, could be applied this way. He’s writing for a regular, traditional paper test, and so he has students come up with their own questions, and these are higher order level thinking questions. So, things like case studies and stuff like that, various applications. He has a template that he has students use and they work in this template and they start to get the idea that there’s a method to this, that if I can solve this kind of an issue, I can solve any kind of issue just like it. It’s really, I think, a fabulous way to get students involved in the test questioning process.

Kevin Patton (00:52:07):

And you know what? It might turn out that some or all of those test items that they eventually come up with are things you can actually take and put right into your test bank and use that as well. So, if you want to know more about TQT, it’s really worth investigating. Go back to episode 70 and check that out. Also, there’s quite a bit of information in HAPS Educator. I’ll be back with more in just a second.

What About Lab Practicals?

Kevin Patton (00:52:39):

Now, circling back to this idea that we have randomized test items, one thing I do when I’m creating my test bank, so here’s a tip, is that I’ll create a question and then I’ll think, “Well, that worked out pretty well for this concept. I’m going to have a similar question about the same concept.” Let’s say it’s one of those items that really is just a fact checking item here. So, I’m going to have some kind of definition. So, I might have one version of the question where I am going to give them a term and they select the correct definition or description.

Kevin Patton (00:53:19):

Then, okay, well, I’m doing that, let’s make another test item. And I can do that quickly because it’s already on my mind, do another test item where I give them a definition and they select the right term that goes with it. So, I might be able to generate four or five questions, they’re just really the same question. One is a multiple choice, one is a fill in the blank, but it’s pretty much the same question. So, I can do that for several of them. Now, when I get to the higher order questions, a lot of those are mini case studies. I’ll say, “Uncle Joe had this issue with his blood pressure,” and ask a question about that.

Kevin Patton (00:53:58):

Then I might come up with another scenario where Uncle Joe is still having elevated blood pressure, then I ask some other question about Uncle Joe’s situation that is not the same question. I’m not asking the same question. They both have to do with blood pressure, but I’m not asking the same thing. They both have something to do with Uncle Joe. I might even put a picture of somebody named… And I actually had an Uncle Joe. He was actually a cousin, but we called him Uncle Joe. I might put a picture of my Uncle Joe up there and say, “Here’s Uncle Joe.” And he did have problems with his blood pressure, now that I’m thinking about it.

Kevin Patton (00:54:35):

But my point is that students still get an Uncle Joe high blood pressure question, and then on their next attempt, there’s the picture of Uncle Joe and it’s asking about blood pressure and so they answer with the same answer because they think they’ve already had that question again. And it’s not. So, this time it’s not a matter of available choices being mixed up in a different order. The actual content has changed, but they’re still in that mindset, that lazy thinking of just looking at the surface and not diving deep enough to really figure things out.

Kevin Patton (00:55:10):

Again, we talked about the advantages of getting out of that mindset. Practice getting out of that mindset of lazy thinking. Be careful, students don’t always recognize the different versions. And again, I think it’s important to be transparent ahead of time that that’s going to happen so that they’re not totally surprised. They’re kind of surprised when it happens to them and then they say, “Oh, darn! Next time I’m not going to let that get me. I’m going to be more careful next time.” Okay. Another practical thing has to do with labs and lab practicals.

Kevin Patton (00:55:43):

I think this would be a great way, and I’ve never done it this way, but I think it’d be a great way to build little test banks for your lab practicals because isn’t that… Lab practicals are really hard for students. I think there are a lot of reasons for that. It’s a different style of tests than most of them are used to, there’s added pressure of time constraints and other people being around and all kinds of things. I mean, all kinds of things that all kind of come together and form of test anxiety that’s going to badly affect how well they do.

Kevin Patton (00:56:20):

And of course, students that are really well prepared and maybe have built their own practice, practicals, on their own in some way by using flashcards or the online flashcards like Anki and Quizlet and things like that and they just practice identifying those bones and bone parts. They practice identifying those tissues. They practice identifying those muscles. They practice finding those nerves and mapping out the parts of the heart and the kidney and all that kind of stuff. They do that ahead of time. But a lot of students can’t or won’t do that. So, maybe we can make that part of our course, right?

Kevin Patton (00:56:58):

We can build a little test bank where they get randomized images of tissues and which tissue is this. Could even have a stage-wise thing, like maybe have two sets of practice quizzes. Here you can take three attempts of this one, then you can take three attempts of the next one. Pass the first one and unlock the second one. That would be a possibility. And in the first one, they can be all multiple choice. Then the second test, all the items in that test bank are asking the same kinds of things, but now you have to fill in the blank.

Kevin Patton (00:57:32):

So, that’s a little bit harder to do, isn’t it? To retrieve the information that well that you can just pull it out of your brain rather than pull it out of a list that’s already given to you. Let’s say you allow three attempts at each of those two sets of tests, that’s six practices at least that students have done. And maybe you can make it unlimited practices, keep doing it until you pass it and then go into the next one, keep doing that until you get the score that you want to get, and then you’ll be ready for the practical.

Kevin Patton (00:58:01):

And I’ll bet you, when the students come in for the practical, then they’re going to be much more prepared if they did that. Because they’re going to have multiple attempts, that’s a lot better than just having a pre-lab quiz, just having that one quiz or two quizzes or whatever it is. This gives them a lot more retrieval practice. And when it comes to identifying tissues, the only way to do that is to practice it a lot. When it comes to identifying bones and bone markings, the only way to do that well and do it quickly enough and confidently enough to do well in a practical is to practice it. So, this provides practice.

Kevin Patton (00:58:39):

And maybe we could do this in a hybrid way so that we have the online randomized practice online and then that’s going to get them ready for a written practice that’s in class. So, there’s our pre-lab quiz, then that leads into the actual practical itself. Not only that, it puts some of the work online. That works well for these hybrid and high flex courses and so on, or if we have to suddenly shift, and I think that’s going to become a typical thing, not just in the near future, but the distant future as well. There are going to be times where we’re going to have to suddenly pivot from face to online teaching and we just never know when that’s going to drop.

Kevin Patton (00:59:27):

So, having that test bank available is going to be a good thing, I think, to help us prepare for that. Maybe we can have some of our practicals be fully online. Like this part of it, we’ll just test that online, this other part, we need to do face to face. So, now you get more tests in a semester than you otherwise would be able to do, because we all know that setting up practicals has all kinds of issues with practical issues, with the space itself and the specimens that you’re using and other people using them, and time to set that up and all those things. I’ve used them in a supplement course where I was helping students prepare for their lab.

Kevin Patton (01:00:08):

And I just used them for speed test drills, where at the end of the class, we have like a speed test. Like how fast in can you identify those tissues? How fast can you identify those muscles? And so on. You might be able to work out something that way as well. So, lots of different possibilities. Once you start down this road, you just think creatively, think outside the box, even more outside the box, and you’re going to come up with some really creative ideas. And if you’re already using some of these creative ideas or you’re thinking up creative ideas right now, why don’t you call in or write in or come on the program and we’ll have a chat about what some of the possibilities might be.

Kevin Patton (01:00:53):

I’d love to have you on this. In the meantime, if you want to review this stuff, they’re links of course as always. But don’t forget that pandemic teaching book that is available free as a download. There’s also a paperback version. It summarizes a lot of what I’ve been talking about in these past three episodes. To get there, you just go to theAPprofessor.org/pandemicteaching. It will not only have the pandemic teaching book, but a lot of past podcast episodes that cover things related to pandemic teaching.

Staying Connected

Kevin Patton (01:01:26):

So, you want to sit down and talk about what’s normal or not normal, or what normal really means, maybe with a peer who teaches A&P, or maybe chat about all the ins and outs of testing A&P students, whether it’s classic methods of testing or wild and wacky methods of testing? Yeah, me too. I want to have that chat, but it’s probably going to work better if whoever I’m talking to has also heard this episode before we talk. But you know what? There’s an easy way to make that happen for you or for your friend, I should say.

Kevin Patton (01:02:16):

Simply go to theAPprofessor.org/refer to get a personalized share link that will not only get your friend all set up in a podcast player of their choice, it’ll also get you on your way to earning a cash reward. Now, if you don’t see links in your podcast player, go to the show notes at the episode page at theAPprofessor.org/101 where you can explore any ideas or sources mentioned in this podcast. And while you’re there, you can claim your digital credential for listening to this episode out. And don’t forget to call in with all your questions and your comments and your suggestions and your average oral body temperatures.

Kevin Patton (01:03:02):

Please, don’t share your rectal body temperatures, just oral body temperatures. And to do that, just call the podcast hotline. That’s 1-833-LION-DEN. That’s 1-833-546-6336. Or send a recording or written message to podcast@theAPprofessor.org. Now, you’re invited to join my private A&P teaching community and join us for our weekly half hour, happy hour, happy half hour, I guess, which we call a TAPP Session. And that’s at theAPprofessor.org/community. I’ll see you down the road.

Aileen (01:03:51):

The A&P Professor is hosted by Dr. Kevin Patton, an award-winning professor and textbook author in human anatomy and physiology.

Kevin Patton (01:04:03):

This episode contains no measurable fat content and is completely gluten free.

This podcast is sponsored by the

Human Anatomy & Physiology Society

This podcast is sponsored by the

Master of Science in

Human Anatomy & Physiology Instruction

Transcripts & captions supported by

The American Association for Anatomy.

Stay Connected

The easiest way to keep up with new episodes is, um, wherever you already listen to audio!

Click here to be notified by email when new episodes become available (make sure The A&P Professor option is checked).

Call in

Record your question or share an idea and I may use it in a future podcast!

Toll-free: 1·833·LION·DEN (1·833·546·6336)

Email: podcast@theAPprofessor.org

Share

Kevin's bestselling book!

Available in paperback

Download a digital copy

Please share with your colleagues!

Tools & Resources

TAPP Science & Education Updates (free)

TextExpander (paste snippets)

Krisp Free Noise-Cancelling App

Snagit & Camtasia (media tools)

Rev.com ($10 off transcriptions, captions)

The A&P Professor Logo Items

(Compensation may be received)

🏅 NOTE: TAPP ed badges and certificates can be claimed until the end of 2025. After that, they remain valid, but no additional credentials can be claimed. This results from the free tier of Canvas Credentials shutting down (and lowest paid tier is far, far away from a cost-effective rate for our level of usage). For more information, visit TAPP ed at theAPprofessor.org/education