Desirable Difficulty

TAPP Radio Episode 78

Episode

Episode | Quick Take

Students want things easy. We often make it hard for them. Host Kevin Patton discusses desirable difficulty and contrasts it with undesirable difficulty. Did you know that healthy human cells have little sections of 4-stranded DNA? We can be better in our web meeting skills. And don’t forget our new online community of anatomy & physiology faculty!

- 00:46 | G4 DNA

- 05:58 | Sponsored by AAA

- 06:38 | Even More Web Meeting Ideas

- 18:55 | Sponsored by HAPI

- 19:55 | Desirable Difficulty

- 35:35 | Sponsored by HAPS

- 36:26 | Our New Online Community

- 39:54 | Staying Connected

Episode | Listen Now

Episode | Show Notes

There are no secrets to success. It is the result of preparation, hard work, and learning from failure. (Colin Powell)

G4 DNA

5 minutes

Oh, come on! Is there really a quadruple-strand DNA in our normal, healthy cells? Or is that only in space aliens? Or zombies?

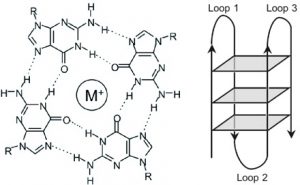

- Quadruple-stranded DNA seen in healthy human cells for the first time (news summary of the discovery) my-ap.us/2RXp7Vt

- Single-molecule visualization of DNA G-quadruplex formation in live cells (journal article in Nature Chemistry) my-ap.us/2EwXr6O

- Image: G-quadruplex by Julian Huppert my-ap.us/3i70AIv

Sponsored by AAA

1 minute

A searchable transcript for this episode, as well as the captioned audiogram of this episode, are sponsored by the American Association for Anatomy (AAA) at anatomy.org.

Don’t forget—HAPS members get a deep discount on AAA membership!

Even More Web Meeting Ideas

12 minutes

Yep, more Zoom. In this segment, Kevin talks about unintended harmful effects of banter, comments on home webcam locations, and turning off video. Plus some advice on backgrounds, both real and virtual. And stuff.

- Communication, Clarity, & Medical Errors | Episode 55

- Pandemic Teaching

- Zooming While Black | Videoconferencing from our private spaces opens a lens on cultural authenticity, professional image, workplace code-switching and white privilege. (article by Shonda Buchanan) my-ap.us/2S3doEQ

- Krisp artificial-inteligence noise-eliminator theAPprofessor.org/krisp

- 4 Tips for Choosing the Best Virtual Backgrounds on Zoom Meetings (blog post) my-ap.us/2EBNN2Z

- pxhere (free photo site) pxhere.com

- Unsplash (free photo site) unsplash.com

- Some sample images suitable for Zoom virtual backgrounds:

- Dramatic sky my-ap.us/3j6Mk3F

- Wilderness my-ap.us/2G9yU8z

- Sunrise my-ap.us/2GcetHU

- Forest road my-ap.us/2S49P1f

- Misty my-ap.us/2FXAQ4j

- Broken sunlight my-ap.us/349gA7w

- Chalk board (black) my-ap.us/3cA78xW

- Green chalk boards my-ap.us/338dFwV

- Geometric shadows my-ap.us/3mWAL1f

- Wood planks my-ap.us/36dHiPb

- Book shelves my-ap.us/337maIg

- Leeds Library my-ap.us/335wwZl

- Gladstone’s Libary my-ap.us/3cz4l86

Sponsored by HAPI Online Graduate Program

1 minute

The Master of Science in Human Anatomy & Physiology Instruction—the MS-HAPI—is a graduate program for A&P teachers, especially for those who already have a graduate/professional degree. A combination of science courses (enough to qualify you to teach at the college level) and courses in contemporary instructional practice, this program helps you be your best in both on-campus and remote teaching. Kevin Patton is a faculty member in this program. Check it out!

Desirable Difficulty

15.5 minutes

Robert Bjork proposed that the difficulties posed by retrieval practice, spacing, and interleaving are desirable difficulties that improve learning. But there are undesirable difficulties that do not help learning. Why must learning be difficult? How can we avoid undesirable difficulty? Hey, wait! Aren’t we supposed to make learning easy for students?!

- Communication, Clarity, & Medical Errors | Episode 55

- More on Spelling, Case, & Grammar | Episode 56

- Desirable Difficulties Perspective on Learning (Robert Bjork’s brief summary of his concept) my-ap.us/3kM0asE

- Making Things Hard on Yourself, But in a Good Way: Creating Desirable Difficulties to Enhance Learning (Elizabeth and Robert Bjork’s contribution to Psychology in the Real World) my-ap.us/3i1Sv7J

Sponsored by HAPS

1 minute

The Human Anatomy & Physiology Society (HAPS) is a sponsor of this podcast. You can help appreciate their support by clicking the link below and checking out the many resources and benefits found there. Watch for virtual town hall meetings and upcoming regional meetings!

Our New Community

3.5 minutes

Take The A&P Professor experience to a new level by joining the new online private community away from distracting social media platforms, tangle email threads, and the roiling sea of available webinars.

- Discussions that matter. In our private space, we can have the vulnerability needed for authentic, deep discussions. Discussions not limited to a sentence or two at a time.

- No ads. No spam. No fake news. No thoughtless re-shares. Just plain old connection with others who do what you do!

- Privacy. The A&P Professor community has the connectivity of Facebook and Twitter, but the security of a private membership site. None of your information can be shared outside the community, so you can share what you like without it being re-shared to the world. Like your dean, for instance. In our community, you can share your frustrations freely. And find support.

- No algorithms. You get to choose what you want to see. You curate your own feed, selecting only those topics that interest you. Join subgroups that resonate with who you are—or who you want to be.

- Access to mentors and like-minded peers. Our community is made up of all kinds of people from all over the world, each with different perspectives and experiences of teaching A&P. Find members near you—or far away. Connect with members online at that moment.

- Courses, groups, and live events. As the community grows, we’ll add mini-courses and micro-courses—some with earned micro-credentials, live virtual office hours with me and other mentors or guests, private special-interest groups, and more.

- There is a very modest subscription fee to join our community. All subscriptions include a free trial period!

- Deep discount on subscription to The A&P Professor community (good all of September 2020) theAPprofessor.org/Insider20

- Deep discount on subscription to The A&P Professor community (good all of September 2020) theAPprofessor.org/Insider20

Need help accessing resources locked behind a paywall?

Check out this advice from Episode 32 to get what you need!

Episode | Captioned Audiogram

Episode | Transcript

The A&P Professor podcast (TAPP radio) episodes are made for listening, not reading. This transcript is provided for your convenience, but hey, it’s just not possible to capture the emphasis and dramatic delivery of the audio version. Or the cool theme music. Or laughs and snorts. And because it’s generated by a combo of machine and human transcription, it may not be exactly right. So I strongly recommend listening by clicking the audio player provided.

This searchable transcript is supported by the

This searchable transcript is supported by the

American Association for Anatomy.

I'm a member—maybe you should be one, too!

Introduction

Kevin Patton:

The diplomat and military leader Colin Powell once said, “There are no secrets to success. It’s the result of preparation, hard work, and learning from failure.”

Aileen:

Welcome to The A&P Professor, a few minutes to focus on teaching human anatomy and physiology with the veteran educator and teaching mentor, your host, Kevin Patton.

Kevin Patton:

In this episode, I discussed a new and crazy form of DNA, more web meeting skills, and desirable difficulty in learning.

G4 DNA

Kevin Patton:

In A&P, what DNA is and how it works comes up from time to time. Even though most of what we teach in A&P, and, really, what any of us know in general about DNA, has been revealed during my lifetime. Okay, the double helix and all that basic stuff was worked out just prior to my birth, but nearly all the rest of it came later. Even so, I have this weird predisposition that this story is closed. Oh, sure, some itty-bitty details have to be uncovered, but, really, I shouldn’t expect something really off the charts to be uncovered later. For example, if my cells right now were making some weird quadruple-stranded form of DNA, in addition to the usual double-stranded double helix that we all know and love, that would be astonishing, right? Well, prepare to be astonished. It happens; and not just in my DNA, in yours, too…

Kevin Patton:

A group of researchers in the UK have discovered evidence of the formation of what they call G-quadruplexes or G4s in normal, living human cells. They have seen something like this in cancer cells in lab experiments before, but this is the first time they’re seeing it in healthy, living human cells. To be clear, this isn’t some long piece of DNA that looks just like a doubled up, intact double helix, like maybe some version of two conjoined sister chromatids. Instead, what a G4 is a localized thing that happens in guanine-rich segments, which is where we get the G from in the name G4. It’s where a strand pulls away from its partner within a double helix, and then folds back on itself a couple of times for a little mini four-stranded structure.

Kevin Patton:

Well, this makes sense because guanine is the only base able to bond with itself and four guanines form a little square that serves as a foundation of the four-stranded structure. Honestly, when I look at a picture of it, which you can see if you follow the links in the show notes or episode page, I wouldn’t say, “Oh, look, a four-stranded DNA molecule, I kind of have to look for it.” Then I find what it first looks like, a region where there’s a little knot, and then I say after looking at it real close, “Oh yeah, I see it. They really are four strands, nearly side by side. And I think see a bear, too, or is that the Big Dipper? I don’t know.”

Kevin Patton:

It seems that these G4s may play a role in holding a segment of DNA open so that it can be read easily by the cell. So the thinking is that the G4s are involved in regulating gene expression. That it’s a kind of epigenetic marker. So when we discussed the double helix structure DNA in our A&P course, we have a choice to them or maybe drop in a little hand that, yeah, well, there’s a lot more to the story that we’re still uncovering in science. Yeah, we’ll just start with the basics in our course and that will serve us well enough, but isn’t it cool that we’re still unraveling the story of DNA? Yeah, and bonus to that is that we get to inject a pun in there, right? Unraveling the story of DNA. Okay, never mind.

Kevin Patton:

But, really, isn’t that joy of scientific discovery, something that our students deserve to hear from us so that we can infect them with it? Which is probably not the best way to express that notion of 2020 is infecting them with the joy of scientific discovery. But be careful about telling your students too much about this because every class has at least one student who will try to argue about the scoring on a test item, some test item about the double helix claiming that normal DNA can have four strands, you said so in class. Now, don’t say that’s not going to happen in your course. You know it will.

Sponsored by AAA

Kevin Patton:

A searchable transcript and a captioned audiogram of this episode are funded by AAA, the American Association for Anatomy at anatomy.org. Hey, I was just at their website. I check in there from time to time because there’s always something new to find, and I found this very interesting report featured on the home page. It’s about prioritizing cadaver dissection and advocating for the funding of and safe reopening of anatomy labs. Check it out at anatomy.org.

Even More Web Meeting Ideas

Kevin Patton:

My favorite topics for these podcast episodes is way bigger than I can possibly get to in a lifetime, and it’s scoring fast that I can check things off that list. And many of you know that few things give me greater joy than to check things off of lists. But some things are more urgent than others, and this one keeps bobbing up to the top of my list saying, “Pick me! Pick me!” It’s another set of tips for web meetings. Yeah, another one. Because, well, now is the time when we need to be quickly becoming a more and more and more expert in teaching and in presenting on Zoom and similar platforms, and interacting professionally in Zoom meetings and conferences and classes and meet-ups. Everything is on Zoom these days. And, of course, helping our students become more professional in doing those things, because we’re not just teaching Anatomy and Physiology, are we? We’re teaching professionalism. Remember back in Episode 55, we talked about professionalism as a course goal? So let’s get to it.

Kevin Patton:

The first thing I want to mention is we need to think carefully about how we interact in a web meeting. An article by a university educator, Shonda Buchanan, really made me think about this. One of the things she talked about or wrote about is how intrusive it is to ask students and colleagues to appear in their personal space, especially for people of color. But I can imagine for others as well such as immigrants, LGBTQ plus individuals, and, well, many others. A black person who may not have access to their usual hair professionals may appear more natural in a Zoom meeting. Let’s face it, our white-dominant culture, maybe even the school you or I teach at, has certain expectations that dress and hairstyles that are not aligned with white dress and hairstyles are deemed as unprofessional or otherwise inappropriate.

Kevin Patton:

Well, so comments are made. Staring happens. Or, deafening silence when a black colleague joins in the banter about how they look in their home environment. It happens. Members of marginalized groups are often very concerned about how their home surroundings will be perceived, how it may or may not trigger thinking and talk about racial stereotypes. Well, if someone says to me, “Wow, your office is so clean,” which, by the way, would never happen. That may or may not harm me, but if I say that to a black person or immigrant, that may be implying that I’m surprised that such a person would ever clean home, and that’s horrible. I don’t want to be that person.

Kevin Patton:

After reading Buchanan’s article and thinking about my students and colleagues, I’m wondering about all those jokes regarding the kids, our pets, or neighbors making noise in the background, or what books are on the shelf behind me; or, in my case, what stuff is piled on the desk that you can glimpse behind me when you see me at a Zoom meeting. I wonder about how that banter affects some people. Am I making people feel bad without meaning to because I’m coming from a place of cultural and racial privilege? Our biases that I might not even realize, are they seeping out and causing harm? So maybe we ought to consider how a person with a different perspective and life experience may feel about that and give them some slack and back off.

Kevin Patton:

Somewhat related to what Buchanan brings up in her article is the notion of having one video turned on during a meeting. Now, I think it’s professional to have one’s video on during a meeting so that we’re present to others, especially the teacher or present, so that we can have something more closely resembling a live meeting or class. So I encourage videos on.

Kevin Patton:

But, on the other hand, I don’t think we should insist on it for everyone all the time. I’ve said this before, but I think it’s worth saying again: It’s okay for our students or colleagues to turn off their video sometimes. Maybe they’re not feeling well. My high schooler vomited shortly before a Zoom meeting and sat there with a bowl in his lap, just in case. But his teacher insisted that his video be on or he’d be counted as absent. It’s not that I didn’t want my kid to be in distress, and if I weren’t working so hard to avoid having a vengeful spirit, I’d have wished that he would have vomited during class just to show that teacher that he shouldn’t insist on having students have their video on all times and under all circumstances. So what I’m advising is having a flexible attitude, always thinking about the best environment for everyone involved. Not be such a hard case, just so I don’t miss out on crushing a slack or trying to con me.

Kevin Patton:

Now, switching to a different gear, I want to talk about Zoom backgrounds. Piggybacking on a point made earlier about how people often judge us on our home surroundings during a home meeting, I suggest thinking about what people see. The best advice is probably to have a corner that is pleasant and can be kept clutter-free and doesn’t have anything that could be used to judge us, because people will. Until you get to be my age, then you don’t care. I’m wearing cargo pants and western boots right now, and I don’t care if you know that. But if you care about being judged on your background, change it. Really, I want to be playful, but I don’t want to be too flip about that judging thing. I really do need to remind myself to make sure that I’m not doing any judging when I’m looking at folks in a web meeting. I want to stay away from joking about what I see there. There are plenty of other ways to be playful in ways that I don’t leave people out or make them sad. As I’ve said, I don’t want to be that person, so I need to work on that.

Kevin Patton:

Oh yeah, I mentioned in a recent episode that the free software called Krisp can filter out background noises. Just go to theAPprofessor.org/krisp, that’s K-R-I-S-P, to download it, or click the link in the show notes or episode page. It’s been working very well for me. Yesterday, I was trying to see if it would block out the sound of the dog barking. So I knocked loudly on my desk to get him to bark, because when he thinks there’s somebody at the door he’ll bark, even if it’s not even coming from the direction where the door is. So I knocked on my desk. Not only did it block off the bark, it blocked my loud knocks which were right next to the microphone. Wow! But now I have to remember to turn it off when I want to do sound effects, like that.

Kevin Patton:

Depending on the resolution of your webcam, you might also find that patterns like herringbone and plaids, especially tight plaids, turn it into a moving sea or colors and patterns even when you’re perfectly still, which breaks my heart because as many of you know, plaid is my favorite color and I wear it a lot. But that’s okay, I have a lot of wide pattern plaids that I can wear and they work fine in video. I’m just saying, check out your clothing for that weird effect.

Kevin Patton:

Another tip is to make sure you have a lot of contrast between your outline and the background. This is especially important if you’re using a virtual background in Zoom because it needs that contrast to keep you from morphing partially into an out of view, like I don’t know, like half a face or something. But even for real life backgrounds, we can all see you better and more naturally if you have a contrasting and rather plain background. So it’s not a bad idea to experiment with a dark background if you light skin, or light hair, or light clothing and accessories; or experiment with a light background if you have dark hair, or dark skin, or dark whatever. For me, kind of neutral, not too dark, not too light backgrounds work best for me because I like combination of colors going on. I have some white hair, some dark grey hair, some light brown skin, some spots of red over my zygomatic bones, and, of course, there’s that colorful personality. So, yeah, lots of colors going on.

Kevin Patton:

So I have to try on a bunch of backgrounds before I find one that works well for me. By the way, if all your vacation photos are too busy or underexposed or too fuzzy to use as a virtual background, don’t sweat it. There are still some great virtual background on the web. All you have to do is a regular web search and you’ll find a bunch of them. What I often do is go to a free photo site and there are all kinds of landscapes, and textures, and artwork that work great. I’ll have a link to some of my favorites in the show notes and the episode page.

Sponsored by HAPI

Kevin Patton:

The free distribution of this podcast is sponsored by the Master of Science in Human Anatomy and Physiology Instruction, the HAPI degree. I’m on the faculty of this program, so I know the incredible value it is for A&P faculty like you. Looking to power up your game in teaching A&P? You may not know it, but HAPI was designed for folks who already have an advanced degree like a Masters or Doctorate, but want to be better equipped as A&P teaching faculty and who want to be more competitive in the job market. We always have some learners who are in the HAPI program as they’re finishing up their doctoral program. It’s hard, but it works for them. Check out this online graduate program at nycc.edu/hapi, that’s H-A-P-I, or click the link in the show notes or episode page.

Desirable Difficulty

Kevin Patton:

Way back in Episodes 55 and 56, when I was explaining why I expect correct spelling of A&P from my students, I told you that I had started thinking about the courses in which I felt like I learned a lot, and I started thinking about the teachers who I thought really made me better in some significant way. I thought about my professors who were tough teachers, who made me uncomfortable by expecting me to stick to it and do the work, and to, well, get things right. I mentioned in those previous episodes that it became more and more clear to me as a teacher that I was becoming more effective and my students were learning more and learning better, and remembering what they learned longer as I expected more of my students.

Kevin Patton:

As that realization eventually dawned on me, I started to become aware of a growing literature on the concept often called desirable difficulty. Robert Bjork is credited with coining this term for effortful learning back in the mid-1990s. In his and Elizabeth Bjork’s lab at UCLA, and many others across the world, have produced a lot of empirical evidence that deep learning requires the effort and difficulty of overcoming obstacles. Those obstacles that students hate, and which often causes students to hate their teachers. That is, until the skills are eventually mastered and the concepts understood. A mastery that comes with repeated trials, corrections and re-trials.

Kevin Patton:

Of course, this fits right in with the overwhelming evidence that vigorous and ongoing retrieval practice is an effective and essential characteristic of solid learning. So, yeah, making students do spaced retrieval practice and interleaving concepts by bringing up past concepts again for review or to expand on that or to apply them in new ways is putting up obstacles for them to overcome, and it’s making things more difficult. But that difficulty is what helps them learn. But I want to back up a bit here to look a little more closely at the nature of this difficulty and to look at what makes any difficulty a student has on learning the desirable kind of difficulty. Because there certainly are the undesirable kinds of difficulty, and I’ll talk about those, too.

Kevin Patton:

But, first, I think what makes a learning difficulty desirable is because it makes learning more effective. That’s because it makes us slow down and really master the concept that we’re wrestling with. If we don’t have to wrestle with it and it’s just sort of falling over and giving up to us, then we either, I don’t know, A, we had already mastered that concept and we’re just reviewing it, which is good because reinforcing learning is good, but it’s not really learning something new, right? So maybe it’s B, somebody else knocked it down for us so that we didn’t have to wrestle it ourselves and master it.

Kevin Patton:

But who would knock it over for us? I know and you know, too. It’s the teacher. The teachers can knock things down to a point that the student can demonstrate the desired outcome without really mastering the concept. We know the ways that teachers can do that. In our desire to help students, sometimes we lower our expectations and give them shortcuts to get to that golden outcome. We want to make it easy to learn the concepts of the course. For a long time, I thought that was my job as an educator, to make it easy for my students. And I guess it is up to a point, but a big part of my job is also to make things difficult for my students. But only difficult in the ways that help them learn, ways that force them to slow down and really wrestle with the concepts.

Kevin Patton:

Applying that analogy of wrestling a little bit further. If I face a wrestling opponent and my teacher knocks them down and pinched them to the ground for me, I’ll never learn how to do it myself. I not only have to try it myself, I have to fail, and not just once but multiple times with multiple opponents. Likewise, if my teacher only matches me to opponents who have no ability to resist me because they are too weak or they are lacking in skills, then I won’t be ready to face a real opponent.

Kevin Patton:

When learning concepts, it work the same way. if my teacher never asks me to do anything that requires to effort in trying to understand it thoroughly, to master it, then when the time comes for me to recall it and employ it, I just won’t be able to do that. I’ll have never mastered it. I tell my students that this is the difference between familiarity and mastery. Familiarity with a concept is important, just like familiarity with one’s wrestling opponent is important. But we need to move on from familiarity to mastery, and that takes work. By work, I mean effort and I mean repetition and I mean coming at it from different angles.

Kevin Patton:

When my students find out that all of their regular tests will be done online with multiple attempts possible to get a better score, and they’re all open book, open notes, open, open, open, they rejoice. They think and sometimes say out loud, “This course will be easy.” Of course, that’s what they all want, right, an easy course. Of course, students almost always want an easy course. I was like that, too, but now I look for difficult courses; difficult in ways that get me to learn. But my students who think they’ll have it easy find out that’s not going to happen in my course. Sure, they look things up, but looking things up and evaluating them slows them down and gets them to learn what’s what in a fairly low pressure way. But then they hit the test items that they can’t so easily figure out using the information that they can find easily in their books or notes or even on the internet. They have to truly wrestle with these items.

Kevin Patton:

But the key is that I’ve made sure they do have the information they need and that they know where to find it, and I make sure that I’ve walked through similar scenarios with them, and I make myself available to help them if they get stuck and if they just don’t know what step to take next, and I give them specific strategies for what to do if they fail, how to analyze their failures and how to fix the issues that their analysis turns out. I’m their wrestling coach. I’m not going to wrestle for them nor am I going to match them up to weaklings. Instead I’m going to give them what they need to know and how to do what they need to do before their first match. Then I’m going to show them how to analyze what happened when they lose and fix that, and then arrange another match for them, and again, and again. Hard work, for sure, but they come out as champions, right?

Kevin Patton:

Okay, so that’s desirable difficulty. But what about undesirable difficulty? That’s what happens when we don’t give our students what they need to be successful in the wrestling with new content. There are all kinds of ways that can happen. For example, we could fail to prepare them properly and we prepare them properly by providing them with a textbook that works well for them. Or another way it could happen is that we fail to give them some pointers before they wrestle, some basic outline of knowledge they need to wrestle with things on their own. Or we match them with an opponent who’s impossible to beat, like a test on things they’re not likely to have ever encountered before or problems so difficult to solve that even we couldn’t figure it out if somebody handed it to us. Or, our test items are so badly written that it’s hard to tell what’s even being asked.

Kevin Patton:

Another way that we can mess with our students is given so many concepts to learn that they simply cannot do it in the time frame needed. Or, another way to make things difficult in an undesirable way is to have a class atmosphere that is a course culture that’s characterized by condescension rather than compassion where students feel bullied or where some students are singled out and made to feel like they’re other in some way, or are otherwise unsupported and unloved.

Kevin Patton:

So, yeah, all those are examples of undesirable difficulty. So it’s not about making things hard for the sake of making things hard for our students, it’s making things hard by implementing proven strategies that make learning more difficult than that easy way of doing things that our students want. So things like lots of retrieval practice. Practice, practice, practice slows things down and thereby makes the course more difficult, but in a productive way. Same with spacing out the retrieval practice, bringing up those concepts again, then waiting a bit, and then again. There’s interleaving, where we cover the structure of the heart in lecture then move on to the respiratory system next week, but coming back to the heart again in lab. That lab lecture mismatch can interleaves things in a way that frustrates students and it frustrates us, too. But it’s also more effective for learning, believe it or not.

Kevin Patton:

The big question that remains for us then is, well, where is the balance? At exactly what point is the difficulty just right? Give me a formula and, by golly, I’ll execute that formula. I’m laughing to myself and I am laughing out loud right now because this reminds me of my students in the HAPI program who want me to give them a sample teaching presentation. They know that I have some particular concepts of how we make and use slides appropriately and combined with other teaching strategies, and they want a template so that they can fill in the blanks, right? But I refuse to give them one because, well, that would be too easy. They wouldn’t learn anything by doing that, right?

Kevin Patton:

I want them to generate something using the principles I’ve given them. Now listen to what I just said, I want them to generate something. I want them to make something. I don’t want them to copy something. I don’t want them to fill in blanks. I want them to make something, and that’s going to be difficult. So they struggle and whine and spit and suffer and, like all students everywhere, they tell me how I should really be teaching the course to make it easier. But I give them multiple attempts with preparatory information and extensive feedback, and I give them support and encouragement. By the end of my trimester with them, they’ve all mastered my particular method, and they’re justifiably proud of the progress they’ve made and the new skills they’ve gained, no matter if they were already masters of teaching at the start.

Kevin Patton:

So, no, I’m not going to give you a template for how to give your course that just right level of difficulty. First, I don’t have a template for that. I’m still working that out myself. But if I did have a template, I still wouldn’t tell you, because, well, you have to do your own wrestling. I firmly believe that teaching is both an art and a science. Science can give us the evidence that we need about the effects of strategies for effortful learning, like spaced retrieval practice and interleaving. But we need to be artists in applying those principles to our courses, and to our students, and to our style of teaching to make something beautiful. That’s what art does, right? It makes something a beauty out of just ordinary objects or substances, and that is part of the fun of teaching and I would never dream of robbing you of that joy.

Sponsored by HAPS

Kevin Patton:

Marketing support for this podcast is provided by HAPS, the Human Anatomy & Physiology Society, promoting excellence in the teaching of human anatomy and physiology for over 30 years. Go visit HAPS at theAPprofessor.org/haps. That’s H-A-P-S. By the way, I’m going to the Joint HAPS-AACA Regional Conference coming up on October 3rd. I went to the last joint regional in Louisville and I had a great time. One thing I loved is the different information and perspective I get from some of the clinical anatomy folks. You ought to try out one of these regionals if you haven’t yet. Just go to theAPprofessor.org/haps.

Our New Online Community

Kevin Patton:

As I said in the previous episode, that is Episode 77, we’re taking The A&P Professor experience to the next level in a new online community where we have each other’s back. It’s a safe space for connecting with others who do what you do, to share ideas, insights, practical tips and to compare notes in an online community away from distracting social media platforms, tangled email threads, and webinars. It’s a great place to connect with me and other experienced mentors to help others struggling with things you’ve mastered and solidify your network of experts for the next time you need help with something quick. There are no ads, no spam, no fake news, and none of your information can be shared outside the community, so you can share what you like without it being re-shared to the world. There are no algorithms. You get to choose what you want to see, and if and when you want to be notified of anything.

Kevin Patton:

Our community is made up of all kinds of people from all over the world, each with different perspectives and experiences of teaching A&P. We’ve just started weekly TAPP sessions. That’s T-A-P-P for The A&P Professor. So we have these weekly TAPP sessions where I, and anybody else who wants to, can just check in and visit for a virtual happy hour every Tuesday afternoon. It’s actually a virtual half hour, happy half hour, I don’t know. It’s 30 minutes. You know that unique method I have for teaching the slides that I mentioned in a previous segment? I’m preparing a mini course in that for our community and, of course, on retrieval practice—and other courses, too. But, hey, we’re just getting started and you might have a course you want to offer.

Kevin Patton:

There’s a very modest subscription fee to join our community. Because we need to get a bunch of folks in there at the start to build the community, I’m offering a special insider’s rate of just $4.99 a month or $49.99 if paid annually, which works out to be about $4.17 a month. That’s almost 70% off the regular subscription fee, which, in turn, is about half of its estimated minimum value. To claim that insider’s plan, just go to theAPprofessor.org/insider20 before the end of September. Once you claim it, that’s the price you pay going forward.

Kevin Patton:

Now, there’s a free trial period before you have to pay, but once you do pay, that price is locked in as long as you’re a member of the community. Yeah, there are student and retiree membership plans, too. If you’re in financial distress, ask about our scholarships. Just contact me to find out about those options. Keep in mind that we’re just starting, so it’s up to you and the other community members to participate and build the community the way we all want it and decide together what courses and events and resources we want or need.

Staying Connected

Kevin Patton:

Hey, don’t forget that I always put links in the show notes and at the episode page at theAPprofessor.org/78 in case you want to further explore any ideas mentioned in this podcast, or if you want to visit our sponsors, and you’re always encouraged to call in with your questions, comments, and ideas at the podcast hotline. That’s 1-833-LION-DEN or 1-833-5466-336. Or send a recording or written message to podcast@theAPprofessor.org. Don’t forget to take me up on that special offer of membership in our new online community. Go to theAPprofessor.org/insider20 before the end of September. After that, you can join at the regular low rate by going to theAPprofessor.org/community. I’ll see you down the road.

Aileen:

The A&P Professor is hosted by Dr. Kevin Patton, an award-winning professor and textbook author in human anatomy and physiology.

Kevin Patton:

I’m a real A&P teacher, not an actor portraying one.

Kevin Patton:

Support for this episode comes from the American Association for Anatomy, the Human Anatomy & Physiology Society, the Master of Science in Human Anatomy & Physiology Instruction, and The A&P Professor community.

This podcast is sponsored by the

Human Anatomy & Physiology Society

This podcast is sponsored by the

Master of Science in

Human Anatomy & Physiology Instruction

Transcripts & captions supported by

The American Association for Anatomy.

Stay Connected

The easiest way to keep up with new episodes is with the free mobile app:

Or wherever you listen to audio!

Click here to be notified by email when new episodes become available (make sure The A&P Professor option is checked).

Call in

Record your question or share an idea and I may use it in a future podcast!

Toll-free: 1·833·LION·DEN (1·833·546·6336)

Email: podcast@theAPprofessor.org

Share

Kevin's bestselling book!

Available in paperback

Download a digital copy

Please share with your colleagues!

Tools & Resources

TAPP Science & Education Updates (free)

TextExpander (paste snippets)

Krisp Free Noise-Cancelling App

Snagit & Camtasia (media tools)

Rev.com ($10 off transcriptions, captions)

The A&P Professor Logo Items

(Compensation may be received)