TAPP Radio Ep. 30 TRANSCRIPT

The Nazi Anatomists – A Conversation with Aaron Fried

The A&P Professor podcast (TAPP radio) episodes are made for listening, not reading. This transcript is provided for your convenience, but hey, it’s just not possible to capture the emphasis and dramatic delivery of the audio version. Or the cool theme music. Or laughs and snorts. And because it’s generated by a combo of machine and human transcription, it may not be exactly right. So I strongly recommend listening by clicking the LISTEN button provided.

This searchable transcript is supported by the

This searchable transcript is supported by the

American Association of Anatomists.

I’m a member—maybe you should be one, too!

Episode 30 Transcript

The Nazi Anatomists- A Conversation with Aaron Fried

Introduction

Kevin Patton: The Nobel laureate Elie Wiesel once said, I never teach the same course twice.

Aileen: Welcome to The A&P Professor. A few minutes to focus on teaching human anatomy and physiology with host, Kevin Patton.

Kevin Patton: This episode includes several updates, and I chat again with Aaron Fried, this time regarding the Nazi anatomists and their impact on anatomy education today.

Listen up: feedback on accommodating hearing impairment

Kevin Patton: Hey there. Before we get started today I have a very important question to ask you and that is did you do your homework? You may recall in the last episode that I asked each of you to mention something about this podcast to at least one other colleague who teaches anatomy and physiology, whether that’s by email, or face to face conversation, or a phone call, or Twitter, or Facebook, or Instagram, or whatever. By doing that, by spreading the word and increasing the total network of listeners that we have, the more questions we’re going to get, and the more feedback we’re going to get, and the more helpful this podcast becomes to everyone. If you didn’t do it, that’s okay. I’m really lenient with podcast homework and so you got another couple of weeks before the next episode to reach out to at least one other colleague and let ’em know something about the podcasts that they might find helpful.

Kevin Patton: In speaking of that useful kind of feedback, in the last episode I was talking about why this podcast is a little louder in volume than maybe some of the other podcasts that you listen to. I mentioned that one of the advantages is that people with hearing impairments like I have, it allows us to turn it up a little bit louder. Whereas, if it’s recorded at a lower volume there’s a limit to how loud we can turn it up and we might not really be able to hear the entire episode. I got some feedback from a friend of mine, Ron Parente, who wanted to discuss this and I didn’t realize that he also has a moderate hearing impairment, and like me, he also wears hearing aids. That led to a discussion of, well, how do we as teachers with some impairment or some challenge, how do we deal with that in the classroom and how do we work that with students and so on?

Kevin Patton: That kind of led to a conversation about how we deal with challenges that our own students have. Then that led to the idea that every time that we build-in accommodations, for example, for the hearing impaired, in all of my teaching materials, or at least most of my teaching materials, I have transcripts or captions so that if I do have a student who is hearing impaired there’s no extra work I need to do to make sure that that student is accessible, but what I found out is that all of my students benefit from that. They all are able to use those transcripts and captions, and sometimes even if a person’s hearing is really good, those extra little helps really help a student learn. There’s something that came up in another previous episode called dual coding where we see something, and hear something, and read something along with it that that can help our brain really absorb the content of what it is that we’re watching by also hearing it and also reading about it.

Kevin Patton: This is a topic that I think is a very important one for any teacher, including A&P teachers, and so it’s going to be the subject of future episode, but in the meantime I strongly recommend that you read a blog article written by Barbara Heard at the HAPS blog, and I’ll have a link to this in the show notes and at the episode page at theAPprofessor.org. It’s entitled, Would You Be Ready? It’s talking about preparing our course materials for the potential that we will have students that need accommodations. Do take a look at that. This is a good opportunity to invite your feedback ahead of time so that when I’m ready to do that episode you’ve already sent in your questions, your comments may be some stories that you have about making our course materials accessible. You can send those to me at podcast@theapprofessor.org or even better call in 1-833-Lion-Den, that’s L-I-O-N-D-E-N. Numerically, it’s 1-833-546-6336.

HAPS is now a sponsor of this podcast!

Kevin Patton: You also have heard me talk about HAPS a lot in this podcast. HAPS is the Human Anatomy and Physiology Society and I’ve been an active member of HAPS for, well, over 30 years. Oh, my gosh. Can I be old enough to do? Yes. I am old enough to have done that, and I have not regretted any moment I spent in a HAPS meeting, in reading the HAPS Educator, and following the HAPS Twitter feed or any of that stuff. There are just too many things to list here and I recommend you go to hapsweb.org and check out of the many programs, and resources, and so on that they have. I’m very happy to announce that beginning with this episode HAPS is now supporting this podcast. Whenever you run into Peter English, the executive director, or Brittany Roberts in our main office, or any of the officers or members of HAPS, mention to them that you appreciate the fact that they’re helping keep this podcast going.

Kevin Patton: Again, that’s hapsweb.org and on Twitter it’s @HumanAandPSoc, and I’ll have the link to that in the show notes and on the episode page at TheAPprofessor.org.

Update in epigenetics

Kevin Patton: In my A&P course I usually spend at least a little bit of time talking about epigenetic inheritance. When we’re talking about the role of DNA, and genes, and why protein synthesis is important in terms of translating that genetic code and putting into play the various biological characteristics that we have as being offspring of our parents. When that comes up I also talk about the fact that we now know that that classic sort of genetic inheritance is accompanied by this epigenetic type of inheritance where chemical markers, chemical additions onto the DNA can be formed during the lifetime of a parent due to various environmental conditions or other biological processes that alter these chemicals that are attached to DNA and they can be passed along to the offspring, and when they are they can affect the biological traits of the offspring. In a way it’s passing along an acquired trait.

Kevin Patton: Of course, there are limits to what can be passed along and how much can be passed along, but it happens. We know that. We’ve demonstrated that already in the research. However, we’re still in the stage of working out exactly how that works. It seems pretty clear that changes in the methyl groups that are attached to DNA has an epigenetic effect. That that process is called methylation and that can be affected by some of these environmental conditions and other biological conditions that create changes in a parent and they can have an effect in the offspring. It’s been very clear how this works being passed along from the maternal side, but on the paternal side the evidence isn’t quite so clear, but we’re starting to work that out. In a recent article that was published in a journal called Molecular Psychiatry, we see an example of some evidence that supports the idea that RNAs can be involved in epigenetic inheritance.

Kevin Patton: I think we’ve already worked out that the short RNAs are involved, but it’s never really been those, by the way, the short RNAs are those with fewer than 200 nucleotides in their sequence. Now we can see that it looks like a long RNA molecules, those with more than 200 nucleotides can also be involved in epigenetic inheritance and in this particular case, what they found was important because it was long RNA that was being passed along by the father and not just the mother. Now we have some explanation for how paternal epigenetic inheritance can occur. I have the links in the show notes and on the episode page at TheAPprofessor.org if you want to look into this more, but it’s another little tidbit we can add to our story and also emphasize the fact that this is a part of the story that is far from being worked out completely.

Handedness in cells

Kevin Patton: There’s a concept in biology called handedness, and that comes from the idea that among humans we tend to either favor our left hand or right hand. For example, I’m right handed. Although I’ve had more than one teacher tell me that I’m ambidextrous, which is supposed to mean you can use your left and right equally well, but in my case they were implying that I can’t use either my left hand or my right hand very well, or very skillfully. Setting that aside for the moment, I want to talk about this idea of handedness because it also is used to describe the mirror image structures and even behaviors that we see all the way down to the molecular level. In chemistry you probably recall talking about the chirality of molecules where you can have a left-handed or right-handed version, or even cells. Now, I don’t remember ever running across this with cells, but cells have handedness too, and that helps them fit together like puzzle pieces when they’re forming membranes.

Kevin Patton: For example, and it’s an important example because that’s what I want to talk about for just a minute, and that is some new research that has come out and it was published in the journal Science Advances. It talks about an enzyme that gets activated in diabetes that it turns out they found it affects the handedness of the endothelial cells that form the wall, or part of the wall, of our blood vessels. If they all have the same handedness they fit together in a certain way, but if this enzyme is activated they can actually change their handedness, or at least some of them do, change their handedness, and so now some of the cells don’t fit together as precisely as they would have otherwise.

Kevin Patton: Now all of these tightly fitting endothelial cells, which are forming a very important functional barrier between the blood and the tissues is now disrupted because you have these regions of the wrong handedness, whether they started out so called left-handed or right-handed, they’ve now switched and they’re different than the other cells surrounding them and so they don’t fit together as well and they make the cells leaky. That adds to the various other mechanisms that are going on in diabetes that disrupts a lot of the different functions of the body. There you go. Our cells are either left-handed or right-handed. I didn’t know that. Now I do.

Kevin Patton: Hey, don’t forget that every episode of The A&P Professor podcast has a searchable transcript that makes it really easy to find something that you heard in a previous episode but weren’t quite sure where it was. We also have captioned audio grams and that transcriptioning and captioning is supported through the American Association of Anatomists, AAA. You can find them at anatomy.org or on Twitter @anatomymeeting.

Featured: The Nazi Anatomists (a chat with Aaron Fried)

Kevin Patton: The featured segment of this episode is the second of two chats I had with my friend Aaron Fried. Aaron is an assistant professor of anatomy and physiology at Mohawk Valley Community College in upstate New York. Besides a lot of experience teaching A&P, instructional design, and teaching methods, Aaron is dedicated to the use of human donor dissection and human and animal tissues for learning and instruction, and is a national speaker on the history of body donation, specializing in the history of body use in Nazi Germany. In episode 29 we talked about some issues surrounding human body donors, which Aaron likes to call silent teachers. In this episode we talk about what he’s learned about some of the Nazi anatomists and how that directly impacts A&P teachers today.

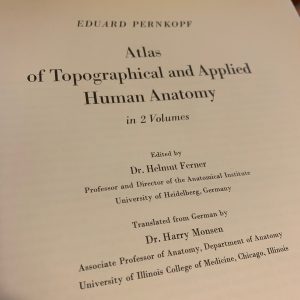

Kevin Patton: Well, we’re here once again with Aaron Fried, who’s been talking to us in the previous episode about the attitudes that we have in using human donors and we learned about why he doesn’t like to use the term cadaver and some of the various issues of having respect for the human people, the real human people who have donated their remains so that we can use it for anatomy education and even in derivative ways such as in various replicas, and models, and even the drawings that we see in anatomy atlases. Aaron, I know you’ve done a lot of research on a series of anatomical drawings done by Eduard Pernkopf and some of his colleagues, and they’re still found an anatomy atlases today. What’s the story behind those illustrations and why is that story important for A&P teachers like me to understand?

Aaron Fried: Kevin, that’s a, you’ve opened Pandora’s box because well, once you ask me questions like this, sometimes it’s hard to get me to stop talking, but …

Kevin Patton: Well, I have the recording switch at my end, so …

Aaron Fried: Yeah, right, you cut me off if you need to.

Kevin Patton: Okay.

Aaron Fried: Before I talk about Pernkopf, I think kind of a generic intro to this is I’ve been lucky enough to work with human donors for a long period of time and I think part of studying Nazi anatomists is why I prefer the term human donor. We use that here at Mohawk Valley Community College because we’re really trying to emphasize a choice, a decision that individuals made. I think probably six, or seven, or eight years ago when I started studying the Nazi anatomists, I read an article at the time, it’s an Emily Bazelon article that was written, it was an online magazine. It was about a senator Todd Akin who made a claim about rape where an individual, women who are legitimately raped have a mechanism to shut that down. The interesting part of the article to me other than that absolutely not being true, is that that research actually comes from a kind of handed down set of citations from a Nazi anatomist named Hermann Stieve who during World War II under Nazi power, was doing research on the female menstrual cycle.

Aaron Fried: What I mean, essentially what he was able to gain access to during that time, was he was able to gain access to these individuals who were being executed by the Nazis and he was able to gain these fresh tissues. The problem, if you have any experience or human donors, the problem is that the type, the age of donation is usually very much in the top ages for humans. I mean in our lab right now we have a 96-year-old female donor and we have an 89-year-old female donor. If we want to study kind of normal reproductive age reproductive systems you don’t get to see that. As an interesting aside to that story, I had expected I was going to go into this studying the Nazis and find out all sorts of information about horrible things that were happening in concentration camps.

Aaron Fried: What I found out is that picture that these Nazi anatomists are working under kind of the eugenics model. The people in the concentration camps are essentially lesser humans. They’re not the most powerful traits in the population, and so they wouldn’t have used them for study. These were actually executed German citizens. The women that Hermann Stieve was using were executed mainly for political dissidence. Essentially they had political views that were the opposite of the Nazi Reich, and they were executed because of those beliefs and anatomists found great benefit from being able to get those tissues and use those tissues for study. I think to get back to Pernkopf, Pernkopf’s a slightly different story because Pernkopf is in Vienna, Austria, and kind of after World War I Austria is separated from the Germanic Empire.

Aaron Fried: Still a lot of the same conditions in Germany. Still fairly fascist regime before World War II. In around 1936 or ’37, Hitler annexes Austria and he says it’s part of the German Reich again. At that time Pernkopf, Eduard Pernkopf becomes the dean of the medical school. Not unlike a lot of other places in Germany at the time, a lot of progressive faculty are kicked out. I think at University of Vienna that was upwards of 70% of the faculty is kicked out just because they’re Jewish, or sympathizers, or just dissenters in general. It creates this real kind of center of eugenics studies and put Pernkopf kind of at the top as the dean, is in charge of acquiring bodies for the medical school. At the same time is also starting to put together a plan to create several atlases. The original plan was it was very, it was a big plan. They ended up publishing before he died, I think, seven volumes of the atlas that each volume was revised over time and they were very detailed drawings.

Aaron Fried: I think one of the things that makes the books unique is that they brought in artists who were watercolor painters, but instead of just looking at dissected specimens they worked with Pernkopf who was an excellent dissector, and so they understood the anatomy and they were able to very accurately capture three dimensional characteristics in their two dimensional paintings. The one thing that Pernkopf really want and away from normal is he urged the painters to use very vivid color. These paintings are described as being very artistic. In fact, one of the reasons the atlases are sought after today is because people view them as kind of these controversial works of art.

Aaron Fried: Where the book starts to become controversial is that during the war, just like Hermann Stieve, Pernkopf is able to gain access to a supply of people who were executed as prisoners of the German Reich. Again, a lot of these people were not, these were not capital murderers. These were individuals who just disagreed with the Reich and were executed for their beliefs, and ended up being dissected at the University of Vienna. These atlases, so after Pernkopf dies, somewhere around the 1960s is when the publisher has some of Pernkopf’s colleagues edit the books and probably much to Pernkopf’s dismay they took out pages and pages of his text and all that remained in the final publications were his artists’ work. They whittled it down to two volumes that were published three times in English, that they were published in addition to German and English they were published in Japanese. They were published French, Spanish. They were published in Italian. They were published as inserts for medications.

Aaron Fried: They were actually using these to sell pharmaceuticals to people in different languages as kind of a professional development opportunity for physicians. One of the things that people noticed is that the artists did things like sign these paintings with, it was common for people to sign the paintings in their artwork, but they were putting swastikas in their signatures or they were putting the SS-lightning-bolts in their signatures and it really wasn’t until the 1990s, so the first edition of Pernkopf was published in 1938, 1939. First time anyone ever really started to raise kind of big questions was around the late 1980s, early 1990s. It wasn’t until then that people started to look into what was going on with these books.

Kevin Patton: Wow, yeah. I have a couple of books where there’s some of those in there and this is something that I’ve talked about to my students before at the beginning of anatomy and physiology I have a little kind of an intro, a discussion of how we know what we know in anatomy and physiology. With the anatomy, clearly it’s dissection. That’s the root of all that we know it. I talk about how the history, the culture, the social setting of any one time sort of determines what kind of experimentation we do and that operates today. There’s all kinds of questions being raised in our society about what is appropriate or not appropriate to do in terms of research and education, and so on. We touched on some of that in the previous episode when we had our earlier discussion, but I did bring up this sort of thing, okay, there are known cases where there are obvious ethical questions about how this material was produced. Yet it’s still in our material. Here’s an atlas that has some of them in it.

Kevin Patton: My question for you, Aaron, is do you use those atlases in your own teaching? Should we be using them in our own teaching? What’s a good way to think about that given their history?

Aaron Fried: Yeah. That’s an interesting question. I think one of the things that brought me into studying Pernkopf in particular, and I think I’ve been hyper focused on Pernkopf for probably the last year. The problem came up, so as I’m studying six or seven years ago, I’m thinking about these Nazi anatomists, and I’m reading, and I’m reading about this Pernkopf atlas controversy. I come across this one reference that says, oh hey, by the way, these Pernkopf images are also in an atlas that was published in the US by Carmine Clemente. I’m like, wait, what? We have that in our lab. I’ve been talking about these Nazis for two years. We have these in our lab? I went into the lab the next morning and I went, started flipping through the book and I was like, oh, that is totally one of the images, one of the authors signatures.

Aaron Fried: Right there in one of the editions of the Clemente Atlas was the signature where one of the swastikas had been erased. It had been doctored so that it didn’t look like that was an issue. I spent a lot of time digging into Pernkopf within the last year, so I want to say last fall I was invited by our colleague Mark Neilson, who has a great dissection program out at the University of Utah, to give my Nazi anatomy talk. I mentioned, oh, Carmen Clemente, these images are in his book. By the way, there’s a whole series of atlases by another German anatomist Sobotta, who the same art has been pulled into those books. Someone sent me an image from one of the most recent versions of Gray’s Anatomy where one of the images in there from one of those artists. I mean, these images kind of had worked their way into a series of different books.

Aaron Fried: As I’m talking about Pernkopf, and the connection to Clemente, and that it’s in our lab, one of Mark’s students raises his hand and he says, well, what do you do about those atlases? I kind of took a deep gulp and I said, I had these analysts in our lab for the last seven years and I don’t know. I don’t know what we should do about them. It’s a very difficult to me decision. First off, I’m not an ethicist, I’m an anatomist. I think of ethical questions all the time, but how do I solve this problem? I spent probably the first couple of months making appointments and going to, it was kind of my tour of Ivy League schools near me. I went to Yale and I saw some of the original editions.

Aaron Fried: I’ve been to Harvard, I’ve been to Johns Hopkins just trying to look at what these books looked like, see if there’s any clues in there, reading everything I could and so I actually ended up, I have a collection of the Pernkopf atlases in my office. We still use the Clemente atlases. Around the same time though I read some work by a woman, Sabine Hildebrandt, who she’s an anatomy professor. She actually became an MD in Germany. She taught in Michigan for a while and now is at Harvard. She has a big emphasis studying these Nazi anatomists and it just, one day out of the blue sent her an email and said, can I come and talk to you about this? I have some questions that you might be able to answer or at least point me in the right direction. She said she would absolutely love to talk to me, but said you need to look this over.

Aaron Fried: She had been working with ethicists, and rabbis, and clergy to try and figure out, is it possible that we can figure out what to do with … I think the big problem that they started with was they’re trying to figure out what can we do with these books or, they over in Germany for example, if they’re digging for anything new, they come across these graves. What do we do with these discovered remains? There’s this very specific protocol they developed called the Vienna protocol and in there there’s a recommendation about Pernkopf and it’s long, and it kind of goes on to say, well, the people probably wouldn’t have consented to display of their body, but in this case, because things have already been done, and it kind of goes on to say, if you use this with people who are going to use their training to do better in the world and if you use the idea of exposing what Pernkopf did and using that as a way to talk about ethics and how not just being a good medical professional doesn’t just mean doing good work in your profession, but also making good ethical choices, that there’s a root, there’s a path to using these materials as long as you acknowledge.

Aaron Fried: What we’ve done is we had a big ceremony last semester where we did a talk on campus about Pernkopf. We created a plaque that acknowledges that we’re not getting rid of the materials because getting rid of the materials is something that the Nazis stood for. We don’t stand for that censorship. Essentially we acknowledge and we try, we have a plaque outside of our donor lab. It says on the way in, we acknowledge that this has happened. We can’t undo it. The best thing we can do is kind of learn from it and going forward make our promise to do as good as we can going forward. We use the materials, but we try to acknowledge what they are and work with them.

Kevin Patton: I wonder if by acknowledging that and making people aware of, it doesn’t make them more informed that things like this have happened in the history of the world and maybe can sort of stand as a warning to not let it happen again. I know I have those thoughts when I think about the history of these things is that it’s important to know about them so that we don’t repeat that again.

Aaron Fried: Yeah. It’s not, my guess is it’s not the last time it’s gonna happen. I mean, even if you look at the story of Henrietta Lacks, I mean, that’s a very much more contemporary example of a woman who her cells were harvested. She thought for just a routine medical procedure, but they were kept alive and people, not only did they end up coming up with good medical treatments but people made money off of that. There’s kind of this conscious effort that I think, especially as anatomists we have to make to do better than maybe a normal person would. I have lots of friends who are academics and I talk to them about this and people will say to me, well, these people are already dead. It doesn’t maybe necessarily mean that you shouldn’t use them. I mean, they’re already there, and I say we owe a better debt to the people who make conscious donation that we understand and recognize that we have to be better.

Kevin Patton: That’s a great point. Aaron, I’ve really enjoyed this conversation. It’s a fascinating story with these illustrations and the history behind them, and I think it brings up some important points and I really appreciate your sharing your perspective on those.

Aaron Fried: Yeah. Thanks for having me, Kevin. I’ll make sure that I get you the link to my website and I’ll put some materials up. I know it’s tough to talk about visual stuff and not be able to-

Kevin Patton: Right.

Aaron Fried: -actually point to them, but I’ll get some of that stuff up there so that if your listeners are interested they can see some of the stuff we’re talking about, but especially the plaque. I think that’s a kind of an important message. Yeah, I’m always interested to talk about this stuff.

Kevin Patton: Okay, great. Well, I’ve already talked to Aaron before we chatted today about him coming on the podcast again in the near future, so look forward to that and I will have a link to Aaron’s website in the show notes for the podcast and also on the episode page at TheAPprofessor.org, but in the meantime, go ahead and give us a call at 1-833-LION-DEN, that’s L-I-O-N-D-E-N, or 1-833-546-6336, or send an email at podcast@theapprofessor.org and give us your reaction to what Aaron’s been talking about, or maybe share some additional information, or perspectives, or resources that we can link to. Aaron, again, thank you very much.

Aaron Fried: All right. Thanks, Kevin.

Kevin Patton: I have some links to Aaron’s website and Instagram in the show notes and at the episode page at TheAPprofessor.org. Aaron is available for speaking engagements anywhere, so feel free to contact him using that information. Don’t forget you have homework due for next time.

Aileen: The A&P Professor is hosted by Kevin Patton, professor, blogger, and textbook author in human anatomy and physiology.

Kevin Patton: Warning, the contents of this episode may be hot.

This podcast is sponsored by the

Human Anatomy & Physiology Society

Stay Connected

The easiest way to keep up with new episodes is with the free mobile app:

Or you can listen in your favorite podcast or radio app.

Click here to be notified by blog post when new episodes become available (make sure The A&P Professor option is checked).

Call in

Record your question or share an idea and I may use it in a future podcast!

Toll-free:

1·833·LION·DEN

(1·833·546·6336)

Local:

1·636·486·4185

Email:

podcast@theAPprofessor.org

Share

Preview of Episode 31

Introduction

Kevin Patton: Hi. This is Kevin Patton with a brief preview podcast for episode 31, which I’m calling The Elephant Episode. In it, I discuss a new discovery regarding how memories are formed in our brain. Well, that’s in human brains. Well, and I suppose also in elephant brains. Yes, elephants do have very good memories. Well, at least that’s my recollection. Specifically, this update on memory focuses on postsynaptic receptors and their role in forming memories. As you probably already suspect, the featured topic will focus on elephants. Long time listeners of this podcast know of my background in zoos and circuses with wild animals, including elephants.

Topics:

- Mechanism of memory formation

- What elephants can teach us about anatomy & physiology

Kevin Patton: It turns out that elephants have a lot they can teach us about human structure and function, and everybody loves elephants, right? What an engaging way to spice up our teaching of human structure and function. So listen to the next episode if you want to hear a few elephant stories. You know, if you use the TAPP app, you’ll get each episode, including these previews, 12 hours earlier than the rest of the world. Just go to your device’s app store and search for The A&P Professor. It’s that easy.

TAPP app:

- List of URLs of curated A&P media we can use in teaching, complied by Barbara Waxer

Kevin Patton: I want to briefly mention that among the bonus content you’ll find there is a list of URLs compiled for us by our guest in episode 28, media professor and copyright expert Barbara Waxer. It’s a list of several curated catalogs of media, such as photos, illustrations and diagrams, specifically for A&P that we can use in our teaching. Maybe some of you have already found it. It’s been there a few weeks. This is a great gift, thanks Barbara, and a very useful tool for teaching A&P. Check it out under the PDF tab in the TAPP app. I had fun dissecting a couple of terms in the last podcast preview, so I thought I’d do it again.

Word dissections:

- pachyderm

- integument

Kevin Patton: I have two terms this time. The first one is pachyderm and that’s a term that refers to elephants and sometimes to related animals. It’s based on an old obsolete term that’s used in taxonomy, but it’s still used today, even by biologists, to refer to elephants. If you break down the word pachyderm, the first part pachy, which is P-A-C-H-Y, means thick or large or massive. Then the second derm, D-E-R-M, well, you already know that means, skin. You put it together, pachyderm, it means thick skin. Elephants do have kind of thick skin, but then again so do humans, right? I mean on the bottom of our feet, that’s pretty thick.

Kevin Patton: Elephants, they have very thin areas of their skin and very thick areas of skin as well just like humans do. It’s just that in some elephants, particularly African elephants, there are a few areas where the keratinized layer gets very, very thick. We’re going to talk about that in episode 31. There are a few science and medical terms that use the term pachy. You don’t run across them very frequently, at least I don’t. One is pachytene, which literally means thick threads, and that’s the third stage of prophase I of meiosis.

Kevin Patton: Now I don’t get that detailed in my description of meiosis in A&P, but if one were to get that detailed, you would run across the term pachytene. That’s the phase during which or the stage of prophase I during which the chromosomes thicken, so that makes sense that you’d use a term that literally means thick threads. Another term that uses pachy is pachymetry, where you use a pachymeter, which is a device that measures the thickness of the cornea. Now the pachymeters in use today are usually ultrasound. In the olden days, they were mostly based on the optical properties of the cornea, but that’s a medical of the pachy or the word part pachy.

Kevin Patton: The other big term that we want to dissect or that I want to dissect, whether you want to or not, is integument. That’s based on the Latin word integumentum, which literally means a covering. If you break down the word parts, it’s in, which literally means in or upon, and teg, T-E-G, which means cover, and then that ending, that suffix ment refers to the result of an action. It’s meant to be a noun, but it’s a noun that’s the result of an action. You put it all together and you get, well, the result of putting a cover upon, which a simpler way of saying that is a covering. That makes sense. The integument is a covering.

Sponsored by HAPS

Kevin Patton: We’re going to talk a little bit about that in the episode as well. The A&P Professor Podcast is sponsored by the Human Anatomy and Physiology Society. Now is a great time to start thinking about going to the annual conference at the end of next May in Portland, Oregon. Go to the website at theAPprofessor.org/haps to find details, including the greatly reduced early bird rates for registration. That’s theAPprofessor.org/H-A-P-S. We’ll have a couple of new book recommendations in The A&P Professor Book Club and they both relate to the content of episode 31. They’re two of my favorite books that relate to human anatomy and physiology.

Kevin Patton: The first one is about the sense of smell, and I’m laughing because the reason that came to mind is because, well, we’re going to be talking about elephants. Well, that’s one of the things that comes to mind when I think about elephants is how they smell. Maybe you’ve had that experience at a zoo or a circus somewhere and you know what elephants smell like. The name of the book is called “The Scent of Desire: Discovering Our Enigmatic Sense of Smell.” It’s written by Rachel Herz. She’s a neuroscientist at Brown University and Boston College, and she specializes in perception and emotion.

Kevin Patton: As a matter of fact, she writes a college textbook called “Sensation and Perception.” In the book, which is a fun book to read, she tells the story of a very early memory of smell that she has. When she was a child, she got to go up to the countryside to visit her grandmother. Her earliest memory of that is her mother driving her out from the city where she lived into the country. As soon as they got to a rural area, she rolled down the window and said, “Ah. Don’t you just love that country air?” Well, just at that moment, they both got this strong whiff of skunk odor.

Kevin Patton: I think her mother was probably being ironic as she said that, but to the little girl, the little Rachel soon to become a neuroscientist, she took that literally and felt like her mother was saying that’s a pleasant odor. So in her mind, the odor of a skunk was always associated with a pleasant memory. That’s how I feel when I smell elephants. When I walk onto a circus light or into a zoo and I smell elephants, boy, I get happy. I get a smile on my face. Everybody else is holding their nose and having a sour look on their face, but not me.

Kevin Patton: Well, Rachel Herz in her book explains the how and the why of that and a whole bunch of other things related to smell that is just fascinating. I think every A&P teacher ought to read it. Another one of my favorite books is a book called “Receptors” by Richard Restak, who has written a lot on neuroscience and has even done a PBS special and so on. This is an old book too. It goes back to 1994, but it’s still a great book. It’s a brief easy read. It’s written for popular consumption, so it’s not overly technical, but it goes through the history of our understanding of how synapses work with a focus on the story of receptors, how they were discovered and why they’re important and some different aspects of them.

Kevin Patton: I love this book so much I used to require my A&P students and also my physiology students to read this book. That’s “Receptors” by Richard Restak. I have links to both books in the show notes and at the episode page at theAPprofessor.org.

Sponsored by AAA

AAA, the American Association of Anatomists, has funded the searchable transcript for this podcast preview and for the full episode. You can find them at anatomy.org. The full elephant episode, episode 31, will become available Monday at midday or Sunday midnight if you have the TAPP app. Talk to you again soon.

Last updated: September 28, 2021 at 21:10 pm